The Shapes of Space

Daisy Atterbury on Form, Language, and Colliding Narratives

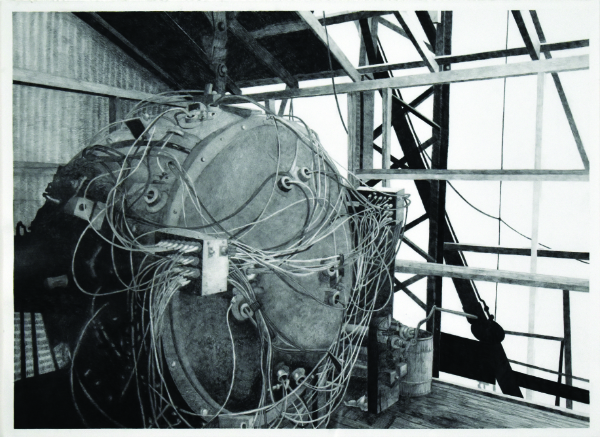

Sedan Crater (Nevada Test Site, after 1972), 2012. Graphite and radioactive

charcoal on paper. Albuquerque Museum, museum purchase 2017, General

Obligation Bonds, PC2020.9.3

Sedan Crater (Nevada Test Site, after 1972), 2012. Graphite and radioactive

charcoal on paper. Albuquerque Museum, museum purchase 2017, General

Obligation Bonds, PC2020.9.3

By Chelsey Johnson Art by Nina Elder

Space is a shapeshifting throughline in Daisy Atterbury’s book The Kármán Line. There’s space as in I need some—a lover pulling away. There’s space misread as emptiness, as in the vast expanses of deserts and oceans, open space where governments detonate practice bombs. The space of the page flows and breaks around prose, poetry, and numbers. Above all else (literally) lies outer space, all stars, infinity, and awe, transcending the line between humanity’s illusory borders and the infinite free space beyond. “The air above me is full of invisible material and energy,” Atterbury writes. “It is full of matter—and memory.”

All these spaces and forms intermingle, collide, and layer upon each other in Atterbury’s debut, published by Rescue Press in 2024. The Kármán Line is a deceptively slender book that contains multitudes. A road trip to Spaceport America is interwoven with reflections on space travel, nuclear disaster, colonialism, identity and belonging, wildfires, and layers of history and violence in New Mexico. Formally, it’s just as adventurous. Narrative prose bursts into fragments, poetry, theory, instructions, text messages, and lists; equations even enter the chat. The quantifiable (physics, economics, nuclear science, one-star motel reviews) and the unquantifiable (love, loss, queerness, metaphor) move side by side.

And New Mexico carries it all. “In a story, setting provides a background against a foreground of self-making,” Atterbury writes. “But here? Setting wants to be foregrounded.”

This powerful sense of place is inextricable from Daisy Atterbury’s form as well as content. Born and raised in New Mexico, Atterbury now lives in Albuquerque and teaches American Studies and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at The University of New Mexico. They spent the first seven years of their life in Shiprock, where their mother worked for the Indian Health Service, and independently, to support uranium miners and their families suffering dire aftereffects of the hazardous work: cancer, renal failure, miscarriages, death.When the family moved to Santa Fe, Atterbury encountered a “jarring” shift in the narrative about nuclear investment and production. The construction of relief route 599 around the city ignited heated discussion about nuclear waste transport and Santa Feans’ exposure to radioactive waste being transported from Los Alamos to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) site. “I was feeling the importance of those conversations, and at the same time I was frustrated that that kind of care wasn’t brought to uranium miners doing work out in the more marginalized communities,” Atterbury said. “I’m still passionate about that, given that there’s an interest in renewing uranium mining [in the Navajo Nation].”

Atterbury moved to the East Coast for college and stayed to earn an MFA and a PhD, but New Mexico continually pulled them back home. In 2010, they co-founded an independent summer program called NM Poetics with Genji Amino. Their mission: “Using poetry as one name for those practices which recall and reconstruct alternative material and social ecologies, we work to attune ourselves to social and aesthetic movement that calls into question prevailing political framework.” In its ten-year run, the free incubator for artists and writers proved transformative.

“[Experimental poetics] always felt political for me, coming up after the post-2008 financial crisis into a world in which it didn’t feel like my generation had a lot to move into. We were expected to be workers in this way that had become a faulty promise,” Atterbury says. “Meeting people who were trying to think through how to create alternative ways of conceiving of the world, and using art and writing to do that, felt really urgent.” For ten years, on a shoestring budget, NM Poetics convened artists and writers from New Mexico and elsewhere for two- to four-week residencies at rotating host sites. Faculty over the years have included luminaries such as Lucy Lippard, Layli Long Soldier, Arthur Sze, and Mei-mei Berssenbrugge. In the theory and practice of experimental poetry, Atterbury also tapped into a deep current of writers past and present “who took really seriously their aesthetic commitments as political scaffolding, as arenas and terrains for articulating other worldviews and other politics.” New forms created new possibilities.

It’s not that Atterbury intended to abandon traditional narrative altogether. But they had become acutely attuned to narrative’s pleasures and dangers, they say, including “both its fruitfulness for drawing people in and creating an experience and working with affect, and also its potential for manipulation.” Their youth in Santa Fe had been one such catalyst.

“Growing up in Santa Fe, I grew up into multiple competing narratives about what the city is and means, and who it’s for and what it stands for and what its values are,” Atterbury says. “Those narratives were very powerful in drawing people into living and acting and working and being in a particular way. And sometimes those narratives were successful in reaching a lot of people and folding people into the idea of what an equitable city can look like—and sometimes those narratives were limiting and were contingent on erasing certain parts of history, erasing Indigenous history, or not talking about violence and the city’s founding in a way that marginalized a lot of people and excluded them from the city’s narratives.” Atterbury grew up to understand narrative as “a material and a texture, a tool that I could explore, unravel, play with, unpack, try to understand in the writing of this book.”

Atterbury lights up when talking—and writing—about the material of language. The Kármán Line wrestles with analogy, synecdoche, taxonomy, and what a poem can possibly contain. The answer to the latter: everything.

“A poem is sparse, it’s economical, but if you’re interested in etymology, you have one word that can mean a whole history, right? And the word that you choose determines everything about the piece,” Atterbury says. “I like the weight that puts on language in an acute, compact space, where it frames and brings forward this idea of what language contains—which is a whole social history.”

Science holds its own poetry as well. Not only does the natural world teem with irresistible metaphors, but storytelling and figurative language are crucial tools for scientists to help us understand the world beyond what we can see. “I think that actually physicists and poets have a lot in common,” Atterbury says. “There’s of course a shared language that is descriptive and world-building and constructive, and then it does meet abstraction at a point.” In the life and writing of Theodore von Kármán, a twentieth-century Hungarian American mathematician and aerospace scientist, Atterbury found “a real kinship” and a way to conceive and frame the work that became this book. Kármán was fascinated with the point at which the wind ceases, which he identified as the demarcation between Earth’s atmosphere and outer space: the Kármán line. Below this line, nations declare borders and boundaries that extend up into the airspace. Beyond it, space is free, unclaimable, open to the entire universe. Encircling a world where humans have mapped and claimed every surface, free space offers another way to conceive of place and property, which dovetails with Atterbury’s earthly concerns of unraveling colonial narratives.

Utopian ideals of space meet the reality of material circumstances in New Mexico’s own Spaceport America near Truth or Consequences, a site Atterbury renders vividly: “From the road, like a lump in an endless horizon, the Spaceport’s soft organic form is a subtle dysregulation in the landscape.” Yet even in its strangeness, Atterbury finds something quintessentially New Mexican about the vexed launchpad:The Spaceport venture in New Mexico feels like it was essentially a failure. That Virgin Galactic, the company it was constructed for, recently transferred its business to the Mojave Air & Space Port launchpad in California, that the New Mexico spaceport primarily hosts school science contests, the government millions in the whole, is no surprise and no real deterrent. This only adds to its appeal, makes it more local.

There’s genuine affection in this assessment, as Atterbury later explains. “The aspirational aspect with the reality of the infrastructure at hand and always ending up in a strangely compromised situation everyone has to accept and deal with, feels familiar. But I love New Mexico. And I loved returning.” Moving back permanently in 2018, Atterbury found a generous, strong community of writers and artists, a community that coalesced even more powerfully during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This sense of belonging was potent, particularly for any artist who has ever felt like an outsider in the culture. “My experience of outsiderness has been vulnerable and challenging,” Atterbury says. As a settler child in the Navajo Nation, Atterbury’s outsider position taught them to listen and observe closely, tuning in to cultural and linguistic nuances that expanded their understanding of place, culture, and colonial assumptions. “Existing in a gendered and sexual body feels misaligned with normative culture and understanding the histories of people inhabiting those kinds of bodies and those kinds of experiences,” Atterbury says. They try “to find the value in the perspective it brings while acknowledging the friction and the hardship and anxiety that can come along with feeling on the outside to a degree.” They write:Meanwhile, we structure social norms around a dislike for seeing someone other than in their place. We fear the sudden wind of a betrayal of position, the ways it blows up our skirts and exposes the truth that we all have choices to make.

Through their writing, Atterbury is “trying to understand how those misalignments provoked in me a desire to understand more about social history, social dynamics, and power dynamics, and how language reflects and produces the ways we understand ourselves in relation to others. It’s a vulnerability I tried to bring to the book at times.” Amid the more intellectual and heady material, “I wanted there to be some real moments where I went to a place of rawness.”

Sometimes that rawness materializes in the recurring storyline of a romantic relationship coming painfully apart. Sometimes it’s in the tenderness and uncertainty of familial silences, in tacit understandings. Sometimes it’s in the unraveling of colonial narratives and Atterbury’s reckoning with their own place in legacies of settler violence. Throughout, the book raises questions of harm and repair, how to reckon with and love the world we have created and live in:To concern yourself in this place with the health, well-being, and sustenance of life and not-life in this place, and to ask of the integrated and delicate network some permission to percolate into this place, may be to admit first that some forms of contact will leave a scar.

Learning to live with your own potential to do damage, and to love what’s damaged and altered, emerges as the primary arc of The Kármán Line. “I think about loving a wrong tree, an invasive tree, its luxuriating spread a reminder of seeds scattered without attention to the disorder the land wanted, how it’s our problem now to love,” Atterbury writes near the end.

“It’s turned out to be my favorite line in the book,” Atterbury says, “because it captures, I think, the incredible challenge in front of us and quandary that we’re in, which is that we have to invest in the world that we’ve built and made … to find a way to invest and love what exists in a grounded real place, to live as we are in a tolerable way and change what we can.”

Even in the effort to become more connected and present, space can still teach us how to live better lives on Earth, Atterbury says. They cite Afrofuturists, Indigenous futurists, and writers such as Ursula K. Le Guin as models who think beyond the fantasies of conquest, solitude, and dissociation, “who use space as a metaphor but from a really grounded and creative place, trying to find a way to actually live in a necessary present, but with tools.” Drawing upon all the disciplines and tools Atterbury gathers for the journey —science, poetry, memoir, cultural histories—The Kármán Line vividly, insistently seeks both to make sense of what is and to imagine what could be.

_

Chelsey Johnson is the author of the novel Stray City and the director of the City of Santa Fe’s Arts & Culture Department.