Father, I Hardly Knew Ye

A Nisei Daughter’s Memories of Japanese American Incarceration

By Nikki Nojima Louis

Pearl Harbor, Honolulu, was attacked at 7:55 a.m. Hawaii time. It was 10:55 a.m. in Seattle on Sunday, December 7, 1941, which also happened to be my fourth birthday. My mother often talked about that day, telling of the two tall white men who entered our home that evening: the FBI. The younger man wiped his feet on the welcome mat when Mommy answered the door. When he removed his hat, she saw that his hair was the color of carrots. The other man gave orders; he did not take off his hat. Daddy was in the bathroom and didn’t come out, though Mommy heard the toilet flush. I was in my jammies, sitting in the kitchen licking Neapolitan ice cream from a spoon. The younger FBI agent said, “Cute baby.” “I’m four!” I replied. They took my father away in handcuffs.

I spent the first four years of my life with my father and the last three years of his life with him when I was sixteen years old. But after the FBI’s visit, my father, my mother, and I never lived together as a family again.

The first generation of Japanese who arrived in the U.S. is called Issei, from the Japanese word ichi, for one. The second generation of Japanese Americans, born to the immigrant Issei, is called Nisei, after the Japanese word ni, for two. The third generation, Sansei, and so on. I was born in 1937 to Shoichi Nojima of Tokyo, Japan, and Michiyo Nakatsu Nojima of Kumamoto, Japan. I’m a Nisei daughter, a child of World War II American incarceration camps, and a product of the Civil Rights Movement. I’m named after that all-American girl, Shirley Temple, the most famous child movie star of her time. I’ve always thought it was ironic that my mother gave me a name she couldn’t pronounce—but “Shulee Tempu” was my mother’s American dream child. When in third grade in Chicago my nickname evolved from Nojima to Nikajima to Nikki. Finally, my mother had a name she could pronounce.

Sadayo is my Japanese middle name, but I like the soft sound of “Sachiyan,” its diminutive, which my parents used. My mother looked up to my father’s family as high class, which in Japan’s feudal class system refers to the samurai, or ruling warrior class. As a Nisei American-born person of Japanese heritage, I straddled two worlds—the world of my parents and centuries of Japanese culture, and the turbulent and rejuvenating times of twentieth-century America.

My father was born in 1888, my mother in 1905. She had been orphaned in the States at age eight and shuttled to uncaring strangers and relatives in Japan. I’ve always thought of my mother’s childhood as a Japanese Jane Eyre. She revered education, classical ballet, high fashion, American movies, and Americans. She had a correspondence degree in dressmaking from Vogue and owned a sewing school in Seattle’s Japantown before the war. My father was soft-spoken, mild-mannered, and enjoyed golf, baseball, Japanese picnics, and people. He loved all forms of shibai, Japanese theater—the classical stillness of Noh drama; the stylized, flamboyant theatrics of kabuki; the love suicides of bunraku puppetry. Everyone in Seattle’s Nihonmachi knew my dad.

Until I was four, I lived with my mother and father on Jackson Street in the Nihonmachi section of Seattle, Washington—Japantown.

Jackson Street was the north–south tributary that divided Japantown from the bustling commerce of Chinatown. Our apartment building and my mother’s sewing school were a block apart, between restaurants, teahouses, bathhouses, barbershops, dance and music schools, the N-P Hotel, Japanese language school, and the Buddhist Church. Seattle’s Nihonmachi was the second largest in the United States. By the 1930s, the Japanese were the largest non-white group in Seattle.

My mother returned to the U.S. in her teens to work on her stepfather’s farm after he remarried. Years later, when she wanted to attend secretarial school in Seattle, her stepmother accused her of selfishness. She remained on the farm to help raise her step-siblings until age twenty-four when the family arranged an omiai, a match with the esteemed and eligible bachelor who fulfilled my mother’s dream of living in Seattle. Shoichi Nojima was a catch—educated, with refined manners, and from a samurai family. His suits were custom-made. Mommy said that when she leaned forward to sign the marriage certificate, she saw that he was forty-one.

My father had an ease in the Japanese community that my mother could never achieve. He was a Japanese American Pacific Northwest golf champion at a time when non-whites could only play on public courses. But I suspect that the seeming ease with which he dealt with the humiliations he was subjected to in white America was hard-won. He’d confided to my mother that as a young boy in Japan, he’d been spoiled and headstrong but that he changed overnight when he almost killed another boy in a fight at school.

As a child, I remember balancing large leather-bound photo albums on my lap, scanning the pages of sepia-toned and black-and-white photos. Community picnics in Seward Park, mushroom picking on Mount Rainier, my mother with Filipino workers at the fishing cannery in Alaska my dad managed in the summer. Photos of the twenty-six-inch-tall Shirley Temple doll in its glass case on the credenza in our dining room and the wall of shelves with tiny glass cases of Japanese dolls in brightly colored kimonos. They were treasured artifacts of the American Dream, in which my mother ardently believed. I would have liked to talk with my dad about his American hopes and dreams.

Throughout my childhood, my mother enthralled me with stories of her mother, who eloped with a doctor’s son to Hawaii; her grandfather, who had been a Buddhist priest in Kumamoto and had committed suicide; our visit to Japan on an ocean liner when I was three years old and our return barely a month before the start of WWII. I recall the Japanese ghost stories she told that were so frightening I had to sleep with the lights on. But most valuable to me now are my mother’s accounts of my father and their life together before the war. One story is of my step-grandmother Nakatsu calling in the middle of the night to beg my father to stop my Uncle Joe from marrying his white girlfriend. In the morning when he returned home, my mother anxiously asked what happened. Daddy, changing into his pajamas, told her bit by bit: they drove around in Joe’s car, talked about sports, and ordered pie and coffee at the Cherry Street Café. “That’s all?” Mommy demanded. Heading for bed, he said that Joe had parked in front of our apartment building, where they sat in silence, the motor running. “Kio tsukete ne, Joe?” my father had finally said, opening the car door. “Take care, okay Joe?” Uncle Joe did not marry his white girlfriend.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the removal of all persons of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast: the designated “war zones” of Washington, Oregon, and California. By spring of that year, we were assigned to temporary “assembly centers” on racetracks and fairgrounds, in stockyard pavilions, and abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps camps—wherever several hundred to several thousand people could be confined while awaiting completion of ten permanent “relocation centers” under the newly organized, civilian-run War Relocation Authority. In their internal memos, government officials, including President Roosevelt, referred to these “relocation centers” as “concentration camps.”

In the meantime, my father, who had been taken from us in December 1941, was held in the secretive system of Department of Justice- and Army-run camps with thousands of other Japanese men who’d been picked up without just cause or due process. In June 1942, following interrogation and confinement at Fort Missoula, Montana and Fort Lincoln, Bismarck, North Dakota, he was transported by train to Lordsburg Internment Camp in New Mexico. It was the largest and the only camp specifically built to house “enemy aliens.”

In May 1942, Mommy and I were bused to the Washington State Fairgrounds in Puyallup, where approximately 7,390 men, women, and children from western Washington and Alaska were crowded into horse stalls, hastily constructed barracks along the racetrack and parking lots, and under the grandstand. I remember the stacks of straw and burlap cases we were pointed toward upon arrival, and the night I spent sweating and scratching from the ticks that came with the straw we’d stuffed into makeshift mattresses. Later, I learned the nickname assigned to the Puyallup Assembly Center was Camp Harmony.

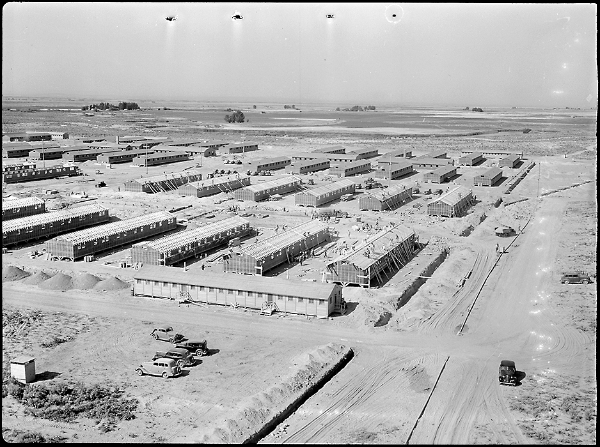

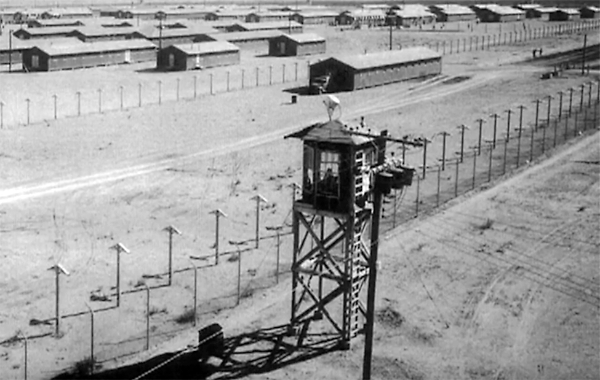

In August 1942, the occupants of Camp Harmony were herded onto railroad cars with blackened windows for the thirty-hour trip to the Magic Valley, seven miles east of Eden, in south-central Idaho. These poetic-sounding names bore no resemblance to the reality of the camp called Minidoka. Forty-four blocks of tar-papered barracks stretched across miles of barren land. At a population of approximately 9,390, the barbed-wire town of Minidoka outnumbered the population of most other Idaho towns. Each block contained twelve barracks divided into sections or “apartments” of varying sizes depending on the number of occupants. Each apartment contained a bare lightbulb in the ceiling, sleeping cots, a potbelly stove, and a coal bucket. Mommy kept a chamber pot in the corner, as the latrines were a distance away. We faced constant blinding sandstorms and extreme temperatures in summer and winter. Gun towers and searchlights that swept across the camp at night completed the look and feel of a concentration camp.

In June 1945, three months before the war’s end, my mother and I joined the diaspora of Japanese Americans who, instead of returning to the West Coast, settled in the Midwest—in our case, a slum apartment on the far north side of Chicago. Each internee released from camp received $25 as a fare-thee-well to three-and-a-half years of incarceration.

My father spent the first year of his imprisonment in Lordsburg, along the Arizona border in the southern boot heel of New Mexico. Lordsburg was a hardscrabble US Army-run camp specifically built to hold the men who had been rounded up by the FBI in the hours and days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. It was run like a prisoner-of-war (POW) camp, although these men were civilians—a bugle wake-up at 6 a.m., lights out at 10 p.m., and regimentation throughout the day. The population of about 1,500 incarcerees was male, and almost entirely Issei. Their average age was fifty-five—far from the youthful enemy soldiers captured in the Pacific that many people in town thought them to be. My father was fifty-four.

In November 1943, Lordsburg was redesignated a POW camp for Italian soldiers captured in North Africa and Italy, and later for German POWs. The Issei were transferred to a camp in Santa Fe, a mile-and-a-half from the downtown Plaza. Although hostility toward the internees was sometimes virulent, there were also exchanges of generosity and compassion that created openings in the barbed wire of fear and hostility.

Ninety-year-old artist Jerry West told me his father, Work Projects Administration (WPA) artist Hal West, worked the night shift as a guard at the Santa Fe Internment Camp. I’ve learned from author Gail Okawa, who shared interviews for her book “Remembering Our Grandfathers’ Exile” with me, that many Santa Feans learned that the Japanese men in their midst were educated, peaceable, and outstanding gardeners. Hal told his son that the men grew vegetables in the arid soil of Santa Fe that New Mexicans had never seen. A friend I housesat for in the Casa Solana neighborhood, where the Santa Fe Camp once stood, remembered elderly neighbors talking about buying eggplants and leafy greens from prisoners who were occasionally allowed to set up vegetable stands outside the Camp. This at a time of rationing when Spam, canned Vienna sausages, and sandy Wonder Bread were our daily fare in the mess halls of Minidoka!

In postwar Chicago, my mother found work as a maid, then as a seamstress in the linen room of the Edgewater Beach Hotel, a luxurious resort on Lake Michigan. My uncle, Frank Kamo, had preceded us from Minidoka and lived in the same building. Mommy and Uncle Frank spoke Japanese and ate Japanese food but were also invested in American ways. Mommy still loved movies, opera, and classical ballet. Whenever the Ballet Russe and American Ballet Theater came to town, we’d ride the el to the Civic Opera House in the downtown Loop. Uncle Frank took me to stage shows at the Chicago and Oriental Theaters, Chicago Cubs baseball games, Riverside Amusement Park, and Lincoln Park Zoo with my best friend, Carol Harmon.

We lived in a slum apartment on the north side of Chicago, where I ran with a rowdy gang of white neighborhood kids but attended ballet school, Girl Scouts, and took piano lessons from Professor Frederic Berendt, a Jewish refugee who’d been conductor of the Vienna State Opera. Ballet school gave me entrée into a part-time career as a professional dancer. Every summer break from school I performed in grandstand shows at state fairs throughout the country, including the segregated South. I was always the only person of color.

When my father was released from the Santa Fe Internment Camp in June 1946, a year after the war ended, he joined us in Chicago. I was nine, and in the Brownies, the junior Girl Scouts. I was a busy kid, very much “lessoned up” by my mother with piano, dance, and school. I ran with different sets of friends from different groups, changing personas to fit in—always the “insider-outsider.”

I wasn’t prepared for this quiet, old-fashioned, older man so unlike my flashy Uncle Frank who bought me bubblegum and banana splits and let me eat hotdogs every other inning at Chicago Cubs games. Frank, Mommy, my piano teacher Professor Berendt, and his wife all spoke fractured English, yet they had adjusted to Chicago’s fast-paced New World-ness. Why couldn’t my dad? One day, when he bought me a hotdog from a street vendor and insisted I eat it at home, I stood on the sidewalk screaming and ran home crying. Although I’d bragged that my daddy was going to be my date for our Brownie troop’s father-daughter dinner, I went instead with our troop leader Ma Mengden’s husband, Pa. I never told my dad about the dinner, nor have I thought of my childish cruelty until now.

When it was announced that my father was returning to Seattle, though, I was genuinely distressed. I remember my mother pointing out the nightly beer battles between the couple next door, the shared bathroom with tenants who never flushed the toilet or scrubbed the tub, the odor of cabbage, booze, and urine in the halls, and the abuse my father endured in the low-paying jobs he was offered. Chicago was stormy, hustling, brawling—hog butcher of the world. I understood.

When I was sixteen, I returned to Seattle to live with my father. He’d suffered a heart attack playing golf on the public course with his longtime friends who’d survived the camps, and I lived with my step-grandparents while he recovered. I finished my senior year at Garfield High School with newfound friends: Anglos, Sephardic Jews, Black Americans, Chinese Americans, and Filipino Americans. The least open and approachable were my fellow Nikkei, Japanese American kids with whom I’d been in Camp Minidoka a few years before. What I didn’t understand then was community trauma. A year later, I enrolled at the University of Washington, where I majored in Literature and Theater.

Life with my dad was easygoing and affectionate. Although his circumstances had been considerably reduced since the war, he still had standing among the Issei and Nisei families that had returned to Seattle. We lived in the Central District—in an ethnically diverse working-class neighborhood that reflected the student population of the high school I attended. Daddy somehow became a kind of Pied Piper of the neighborhood. Without seeming to exert effort, he attracted little kids and a dog, Mutty, and a cat, Kitty, who belonged to the Black family next door but lived mostly at our apartment. Every day, by the time he got off the Jefferson Street bus after work to walk the two blocks home, Mutty, Kitty, and some kids would be trailing after him. Maybe it was the bag of Japanese senbei crackers he always carried?

When he suffered his fatal heart attack in December 1957, a couple of weeks after my twentieth birthday and two days before Christmas, I had completed finals at the University of Washington the day before. I’d spent the previous year dancing in California and Las Vegas but declined an offer to perform at Radio City Music Hall in New York because I wanted to return to school. It was real luck that I was home that fateful day. In the morning, my father called out in pain from his room. Mutty and Kitty hovered anxiously on his bed. The doctor rushed over; the ambulance came. He died soon after arriving at Harborview Hospital. My mother flew in from Chicago—the first time she’d been in Seattle since 1942—and fainted at the funeral.

During the time I lived with my dad as a teenager, I remember him speaking of his camp experience only once, and that was about the generosity of a Santa Fe guard. I don’t recall the circumstances of that conversation—I had hardly any interest or curiosity about the camp experience then—but I do remember that my dad said the guard called him by his camp nickname, “Sam,” and told him to walk around the Plaza and enjoy himself. Years later, when I related this incident to members of my Asian American theater group in Seattle, an actor who was particularly embittered by his family’s Minidoka experience, opined that the guard ditched my dad to get together with a girlfriend, or to grab a beer, or for any other reason than kindness.

So, I was later grateful to learn of Reverend Charles Kingsolving, who received death threats for conducting Episcopalian services at the Camp and offering evening prayers to “anyone who wanted them.” His son John Kingsolving related to author Gail Okawa that when the phone rang in their house, his dad would say, “Another damn phone call,” and hang up. Emotions were fraught because of New Mexico’s heavy losses in the Battle of Bataan in the Philippines and the atrocities of the Bataan Death March. Gail has also shared with me that Joe Valdes, a former mayor of Santa Fe who ran errands at the Cash & Carry Grocery on Palace Avenue when he was thirteen, verified what my father had told me—that many of the guards treated their prisoners humanely.

I’ve spent the past fifteen years in and out of New Mexico, fact-finding the lives of the Issei men held in Lordsburg and Santa Fe: community leaders, Buddhists and Shinto priests, Christian ministers, Japanese language teachers, businessmen, journalists, fishing boat owners. Many had lived in the U.S. for decades and had fathered American-born children, as had my father, but were denied citizenship due to long-held Asian Exclusion laws. They were allowed to live in this country only as “resident aliens.” The attack on Pearl Harbor changed their status to “enemy alien,” and their roundup by the FBI and military was immediate and swift.

I’ve scrutinized group photographs of prisoners in my research of the Lordsburg and Santa Fe Camps, searching for the face of my father. At one time he sent us a photo of himself and a group of other men posing with golf clubs—one of many official photos I’ve seen that documented the recreational facilities which the men were allowed. I hated that photograph for making Santa Fe look like a resort.

In 2012, I attended a symposium at the New Mexico History Museum on the Santa Fe Internment Camp. At one point in the program, Mollie Pressler, curator of the Lordsburg Museum, asked the audience if they knew of anyone who’d been in the Lordsburg Internment Camp during World War II. I raised my hand and said, “Shoichi Nojima.” Mollie took out a stack of rubber-banded 3 × 5 index cards from a plastic cake box and removed a single card from the stack. She announced to the audience my father’s name, vital statistics, and the date he entered Lordsburg Camp with one dollar in his sweater pocket. This began my relationship with the Lordsburg Museum, which led to research, interviews, and writing of a reader’s theater script on the Camp and the controversial deadly shootings of two elderly prisoners by a guard in 1942. My father was in Lordsburg at the time of the shootings. Did he know these men? Was he aware of the shootings? Did he fear for his safety?

Barbara Kingsolver writes that “memory is a complicated thing—a relative to truth but not its twin.” This challenges the assumption that our memories accurately reflect reality. In my case, it challenges the idea that if I’d been able to sit down for a conversation with my dad about his feelings or experiences or anything—we would have gotten “to the truth of the matter.” While I don’t know all the facts of my father’s life, I feel I know much of his truth. I’m certain that being with him the last three years of his life—and even the first four years of my childhood—was a gift of time and not a lament for the time we didn’t have. I feel I “know” my father through my mother’s interpretations of him, through the time I spent with him as a teenager, and through the journey of discovery I’ve been on since I arrived in New Mexico in 2008 as a newly minted PhD at age seventy. Sixteen years later, I’m still here and learning.

My time in Santa Fe parallels my father’s—although our stays are more than seventy years apart. I’ve had the privilege of meeting Santa Feans with childhood memories of the Camp and its inhabitants, and through them have felt the world in which my father had lived. The two worlds I straddle are in balance; the past informs the present. When I view the adobe structures of Santa Fe, stroll across the Plaza, or look up at the same night sky, I know my father has been here before me.

—

Nikki Nojima Louis is a child of American concentration camps and the protégé of the Civil Rights Movement. In the Pacific Northwest, she was active in multicultural theater as a writer, performer, and producer of women’s, peace, and social justice shows. In New Mexico, she thrives on writing, directing, and touring living history plays that connect the past to the present and us to one another. Louis received the 2024 Upstander Award from the Holocaust and Intolerance Museum, and subsequently discovered that an upstander is a person who speaks out and stands up in support of others. She strives to be that person.