Dancing Back to the Desert

From Hoop Dancing in Gallup to the New York City Ballet

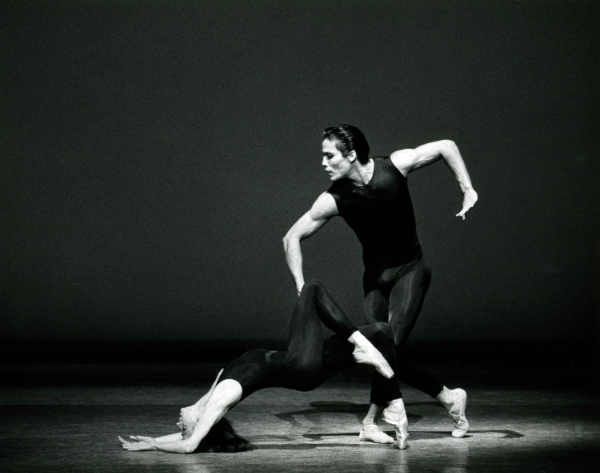

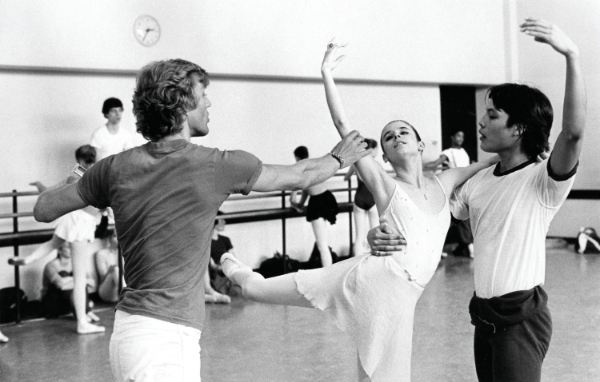

New York City Ballet dancer Jock Soto

in a studio photo in costume for Calcium Light Night, choreographed by Peter Martins, 1986. Photograph

by Martha Swope. The New York Public Library

Digital Collections.

New York City Ballet dancer Jock Soto

in a studio photo in costume for Calcium Light Night, choreographed by Peter Martins, 1986. Photograph

by Martha Swope. The New York Public Library

Digital Collections.

By Ungelbah Dávila

I follow Jock Soto across the TV screen, measuring his movements in lengths. The length of an arm, reaching out, every finger engaged with emotion. The length of his neck as his head looks skyward, his black hair blending into the stage, his brown throat exposed, veins pulsing. The length of his legs fluttering through the air in a moment of ethereal flight. The length of his torso bending to the side like a crescent moon. The length of his career with the New York City Ballet (NYCB): twenty-four years.

And then, the house lights are on and covering the stage where only moments ago Soto soared through the air like a dove, are hundreds of rose petals.

It’s a Sunday in June 2005, and Soto has just danced his last ballet as a principal of the NYCB. The program, Dance at the Gym, features ballets by five different choreographers—Jerome Robbins, Peter Martins, Christopher Wheeldon, Lynne Taylor-Corbett, and George Balanchine. Here, Soto takes his farewell bow before retiring at age forty, as ballerina Wendy Whelan, Soto’s longtime dance partner, whispers, “I love you.” Backstage, he embraces his parents, Josephine Towne (Diné) and José Soto (Puerto Rican), whose unyielding support set him on this path thirty-five years ago in a strip mall two thousand miles away in Phoenix, Arizona.

Today, Soto resides in Eagle Nest, New Mexico, with his husband Luis Fuentes in a home he had built for his parents with design input from his mom. He is still widely recognized as one of his generation’s most accomplished and influential male ballet dancers. In 2017, he received the New Mexico state Certificate of Appreciation for his contribution to the arts, and he is a recipient of the 2024 Governor’s Arts Awards. His illustrious career with the NYCB and the bittersweet night of his final performance are all captured forever in the documentary Water Flowing Together by Gwendolen Cates, in which his late mother recalls having several false labors with Jock because, she theorized, he was dancing in her belly.

“She often said that, and I didn’t believe her!” laughs Soto. “But I had an accident where I was in the hospital, dancing, apparently, in the bed, and they had to tie down my hands and wrists because I would just kick and do all this stuff. So yeah, now we believe that I was dancing in her womb.”

For the past fifty-nine years, music and dance have been a constant in Soto’s life. Born in Gallup in 1965, he spent his early childhood on the Navajo Nation, where he began hoop dancing with his mother at three. “My grandfather was known as a famous drummer and singer,” says Soto. “He’d take my mother and me out to the front of their little shack on the reservation, and he taught me how to dance. He’d say, ‘Follow your mom,’ and I was just like, ‘Oh, my God, I love this!’ And he would play and sing while we danced.”

His grandfather made Soto hoops to dance with, and he still remembers dancing with his mother at rodeos, intertwining intricate choreography with her for the cheers of the crowd. Amid the heartbeat of the drum, the dust from moccasins gliding on the desert floor, and the life-affirming symbology of the hoop, Soto garnered his first understanding of rhythm, performance, physical and spiritual balance, and using his body to tell a story.

“My mom was the first Navajo woman who did the hoop dance because it was always done by male dancers,” he says. “I tell my students now, I say, ‘Before you even walk into the studio, you have to think about what you’re going to learn and how you present yourself.’ I think a lot of it has to do with my heritage. I have had that awareness since I began hoop dancing at age three.”

The Soto family spent time on the powwow circuit, performing the hoop dance, selling crafts and fry bread, and living by modest means. And then one day in Chinle, Arizona, George Balanchine’s 1967 ballet, Jewels, crackled through the TV set and Soto’s world was forever changed. He was captivated by the weightlessness and masculinity of dancer Edward Villella, whom he calls his idol, as he lifted ballerina Patricia McBride through the air. “I saw that ballet on television, and I walked to my mom’s bedroom at five years old, and I said, ‘That’s what I want to do!’” says Soto.

In the 1970s, boys learning ballet was practically unheard of in rural Arizona, but his parents found Soto a school ninety minutes away in Phoenix. He was the only boy enrolled and after auditioning was given a scholarship to attend. It quickly became apparent that Soto possessed a rare gift, and his teacher urged him to apply to the School of American Ballet. At just thirteen, Soto was accepted into George Balanchine’s prestigious New York City school with a scholarship from the Ford Foundation.

With a rare and life-changing opportunity across the country in what may as well have been on a different planet from the tinkling bells of sheep corrals, warm scent of fry bread cooking on a wood stove, and sprawling red earth of Diné Bikéyah, his parents were met with a difficult decision. There was no way the Soto family could afford to live in New York City, so in an act of sheer faith, they left him on his own in the biggest city in the U.S. He called Manhattan home for the next thirty-eight years and remembers lying about his age to rent an apartment with other boys, pretending to be an understudy to sneak into theater wings and watch the NYCB, and giving up correspondence classes to focus on ballet full time.

“I survived with five other students, and you know, if we needed to borrow fifty cents for a hot dog, that’s how we ate,” he recalls. “But, my whole passion was to be in the studio with my teacher. That’s all I lived for. That’s all I wanted to do. When George Balanchine took me into the [NYCB] company, I was like, ‘I’m good now, everything’s good. This is my life.’ And from then on, until I retired at forty, that was my life.”

Despite having what is considered an atypical dancer’s body, Soto’s discipline and inherent talent landed him a spot in the NYCB by age sixteen.

“The directors that I worked with believed in me because I actually worked every single day for twelve hours a day. I didn’t have the body or the technique or the physicality that they had, and I wished every single day that I could look like them. I had to make myself look like them; that was my goal. Somehow, my directors saw my drive,” he says.

While Soto’s exceptional technique, powerful stage presence, and unique ability to blend strength with fluidity made him a standout performer, it wasn’t without intense physical and mental challenges. He remembers dancing early on between two male ballet dancers and comparing their bodies to his. At the time, he didn’t believe his body was as “exceptional” as his peers’ but resolved to work until it was.

“Sometimes I’d go home, and I’d just be crying, and I would think, ‘Why are these people treating me this way? Why are they picking on me? Is it because I look different?’ I questioned myself all the time. But my whole life was walking into that theater and walking out happy and proud,” says Soto. “My director at the time, after George Balanchine died, said he was going to promote me, but, and you could say this back then, he told me ‘You’re too heavy.’ Two weeks later, I had lost fifteen pounds because I thought if I want to be on stage, and if I want to dance like them, I have to become what these people [the audience] are paying for. It was a huge deal for me because I was eighteen, and two weeks later, I was promoted to a principal dancer, one of the leads, and I thought: this is what it takes now.”

Throughout his illustrious career with the NYCB, Soto became known for his versatility and artistic depth. He performed an extensive repertoire that included classical and contemporary works, collaborating with some of the most renowned choreographers of the twentieth century, including George Balanchine, Jerome Robbins, and Peter Martins. He danced feature roles in over forty ballets, many created specifically for him. His interpretations of Balanchine’s works, in particular, were highly praised, as he brought a unique sensitivity and understanding to the complex choreography.

“It’s a hard career to have, but the strength that my mother gave me is what made my career, I think,” says Soto. “I never, ever thought that I would be famous, and when people announce my name and say, ‘the famous whatever,’ I’m just like, ‘No, I just did what I needed to do.’”

Soto’s ability to partner with renowned ballerinas such as Heather Watts, Darci Kistler, and Whelan also earned him praise for handling tricky, breathtaking lifts with confidence. He attributes the ability to create sensuous and romantic stage relationships to getting to know the ballerinas on and off the stage.

“We would end rehearsal, go have lunch, and we’d talk about everything that they were going through, what they were interested in, or what I was going through. So, if I was dancing with somebody that I didn’t know much about, I’d want to get to know them better because I wanted to bring that to the stage,” says Soto.

While Soto is gay, he found that sharing a type of intimacy with his dance partner was essential. “There was one ballerina who I danced with a few times, who was a lot younger than me. I got frustrated because she was frustrated. I said, ‘Imagine that we’re having sex.’ I said, ‘This is about movement.’ It made sense to her, how every step you take has to be important. I said, ‘You have to think about how I’m putting your foot down on the floor.’ And guess what? That night, she brought the house down, and I say ‘she’ because she understood how I was moving and how I was doing all this stuff and manipulating her.”

In the nineteen years since retiring as a dancer, Soto has enjoyed a second act as a choreographer and instructor. He became a faculty member at the School of American Ballet, before permanently relocating to New Mexico, where he now teaches and choreographs for Ballet Taos and Festival Ballet Albuquerque. He was also a guest instructor at the Jillana School, an intensive summer dance program in the Taos Ski Valley, which closed during the pandemic.

Soto says he never expected to be a teacher or choreographer, but the great teachers he had inspired him to carry on the torch. “My life right now is going towards trying to inspire kids and dancers and show them and talk to them about what I’ve gone through,” he says. “You cannot walk into a studio of whoever you’re teaching or choreographing […] as a tyrant because people are scared of you already. I’m just trying to pass on what I’ve learned. And I can’t pass on what I’ve learned in negativity.”

In a dance studio at the Jillana School in 2019, a room of young ballerinas giggle as Soto corrects their technique or reminds them of their steps. “OK, that was really bad,” he says with a laugh, his voice soft and patient. The piano picks up, and the girls try again while Soto walks the room clapping the rhythm, a huge, proud smile across his face.

—

Ungelbah Dávila is a Diné writer and photographer from New Mexico.