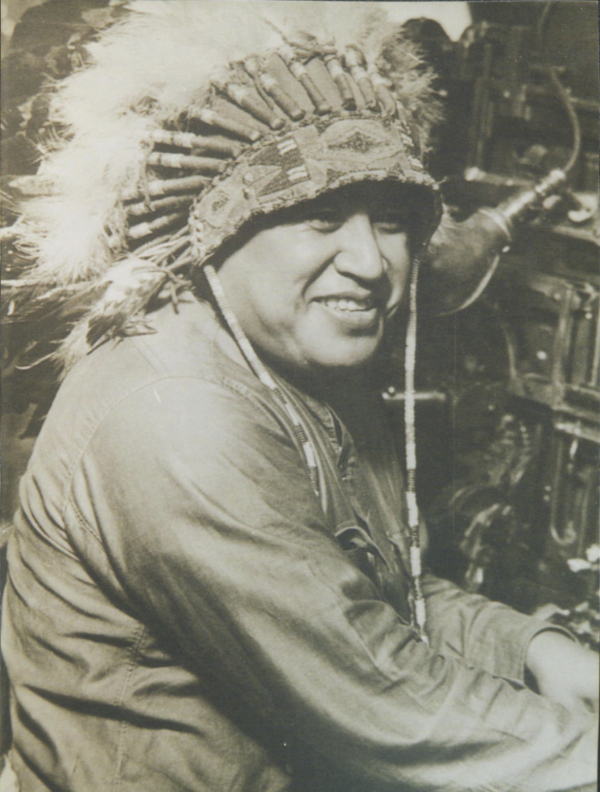

Almost Yuman (1972)

Deborah Jackson Taffa

Remembering the Animas River helps me forget, at least for a moment, the challenges, fears, and feelings of inadequacy I experienced in my childhood. Memoria praeteritorum bonorum. My own set of rose-colored glasses. A trick of the mind that helps me highlight the peaceful days, the quiet ones that punctuated the violence, pressures, and confusion of being a Native girl in a northwestern New Mexico town where cowboys still hated Indians, and three White teenagers murdered three Native men just before my family and I moved there for my father’s new job. Navajo people marched in the streets, and though we missed the protests and backlash, the town’s tension remained consistent, even after the Civil Rights Commission came in to keep the peace.

My early childhood took place in an era when good Native families didn’t move off the reservation because close friends and relatives called relocation a betrayal. It was a time of conflicting choices, when young people who grew up on the reservation faced a dilemma that pitted double-digit inflation and high reservation unemployment against the desire to belong to their tribe. It was a time when my father realized he wanted to be an individual, and my parents decided they wanted their kids to be mainstream Americans, thereby passing down an implicit appreciation of social climbing along with and in conflict with the realization that our people are excluded, ironically, from the central mythologies of the American identity.

I want to say ours is the iconic American story but that would insult non-Natives, the decent folk for whom the knowledge of broken treaties and forced assimilation is already a burden, and for whom oppression is likely also an inheritance. I don’t tell this story to create a divide. I tell it because there are too many dark corners in America that can be relieved of persistent shadows by shining a little light. I tell it because our story belongs to all Americans, some of whom may be surprised by its history. I tell it to celebrate our survival as a culture, as well as the hope, strength, and grace of my family.

This story is as common as dirt. Thousands of Native Americans in California, Arizona, and New Mexico could tell it. Anyone with a grandpa who was haunted by Indian boarding school, who stung his family like a dust devil when he drank. Anyone with a grandma who washed laundry until her fingernails cracked and bled, who went without eating when there weren’t enough groceries because she wanted her ten kids to have a few extra bites. Anyone with a mother who kept secrets so her kids wouldn’t find out about their father’s jailbird past. Anyone with a father who chose the violence of industrial labor over the violence of reservation life because he wanted his kids to get through private school and make better lives for themselves.

So many people could tell this story; it is shocking how little it has been told. Too many mothers have watched their kids thrown into cop cars without protest. Too many aunties have put ice on black eyes without saying a word. Too many grandmothers have watched their grandchildren, their hope for the future, head out to a party and never come home. Too many girls have pretended nothing happened after experiencing sexual harassment, only to redirect the hate towards the innocent face staring back at them in the mirror.

Native memoirs are rare because there are rules on the reservation. Talking to outsiders is taboo. We fear appropriation and fight about who has the right to speak. So why tell my story? Because I want Native kids to feel more connected and less lonely. Because I hate the portrayal of my people as dependents unable to better their own circumstances. Because I need to understand what aspects of my personality were seeded in that New Mexican town all those years ago. And because it has been so long since the events in this book took place, I am able to enjoy some gallows humor in the telling.

My inheritance stretches back to the Anasazi, over a thousand years in the cacti, sage, and sandstone lands, in the desert canyons, adobe homes, and turquoise stone Southwest. America runs like a river through my veins, yet throughout my childhood, Native representation gathered dust in museums. On television, in books, I saw costumes and mascots—never a portrayal of a mixed-tribe Native girl listening to music on her Walkman. Without a contemporary likeness of myself in the media, there was no confirmation that anything I experienced in my childhood was real.

My father was born in 1941 and he taught me never to confuse pity with comprehension. His Quechan (Yuma) grandfather was born in a time when California’s Indian population had plummeted ninety percent because of foreign diseases, Catholic slave-labor, and the government’s hiring of private militia to bring in Indian scalps. California’s first governor, Peter Hardeman Burnett, openly promoted genocide, calling for “a war of extermination” in his second state address. With the help of the U.S. Army, the California legislature distributed weapons to vigilantes who raided Native homes and killed 100,000 of my ancestors in the first two years of the Gold Rush alone. $1.1 million was paid to these murderers, and when it was done, the U.S. Congress agreed to reimburse the state.

When I was younger, I avoided writing about these atrocities. I told myself it sounded conceited. To have survived that much violence, my ancestors must have been powerful. It was like I was claiming to have super genes. Today I know my hesitation was shame: the silence that follows an apocalypse. To talk about what we suffered, to concede that we were victims, was not something we did in my family. And yet to write about the culture that was taken via the government’s assimilation policies, I must acknowledge the pain and remember the beauty in the middle-class life my parents jerry-rigged for me and my siblings in the high-desert arroyos and sun-scorched histories of the American Southwest.

I was raised to believe in the reciprocity of the land, and I know that, if I went back now, I would see that our favorite camping spot near Purgatory has aged just as much as me. During my childhood in the 1980s, my family and I were fishing on the shores of change: the Animas was the last free-flowing water in Colorado before it was dammed at the start of the twenty-first century; a bald eagle refuge not yet injured by the wastewater that bled from the Gold King Mine in 2015. Dad said the river’s full name was the Río de las Ánimas Perdidas, or the River of Lost Souls. He said if we got up early, we might get lucky and see them: the spirits of our ancestors floating downstream in the early morning fog.

I remember waking up and calling Dad to bring me my basketball shoes while I was still in my sleeping bag. Warm from their place near the fire, the shoes’ canvas made my toes cozy. I ran down to the water, where the grass was stiff with frost, and there was the smell of smoky pine in every breath. I squatted to wash my face, squinting at the outline of what I imagined to be the spirits of our ancestors on the other shore. If only I knew their names, I thought, maybe I could help them get home.

Today, they are the ones bringing me home. Reflecting on my visit to the Animas River when I was twelve, I hold my ancestors close to my heart, knowing I too will be an ancestor someday, adding to the chain of lives that came before.

With death as my guide, I remember what’s important, and listen for the river even now. “Do not participate in the erasure of your own people,” the voices murmur. “Do not be a silent witness as we fade.”

We sisters were broken girls. We twisted our ankles sailing off playground swings, toppled out of tamarisk trees, plucked yellow-jacket and broken glass stingers out of our skin. We slammed our fingers in car doors, burned our feet in campfires, and then sat in the waiting room at the Yuma Indian Hospital, ice pressed to injuries.

Joan broke her wrist. I broke my collar bone. Lori had a two-inch scar down the center of her chest. Monica slipped through the handrails of a tall metal slide and landed twenty feet below. The reservation was rowdy in the 1970s. By the time I was three, scars were a main source of pride.

Put a little whiskey in Dad’s beer, and he got to talking about his friends. Crushed under a fast-moving train. Stabbed in the chest during an alley fight. Propped against a tree at a public park with a hot needle sticking out of an arm. Killed in a landmine explosion in Vietnam. Mom tried to shush Dad when he told us his stories. But he said we needed to know the truth if we were going to survive, to hear how tough the world could be.

Swagger was a sure way for us kids to get praise. Despondency hung over the reservation, and when toddlers and children acted rebellious, adults saw hope and verve. A sassy girl was a girl who might make it, even against the odds. My sisters and I did what we could to impress.

We rejected all things girly. We painted our dolls’ faces with markers, tattooing their chins in the style of our female ancestors. We chopped off their hair, and when they grew grotesque, threw their heads in the trashcan, and danced their bodies around, calling out like barkers selling tickets to see Geronimo at the World’s Fair: “Come and see the Amazing Headless Wonders!” We were unruly Indian girls, not the friendly Thanksgiving Day types who knew how to cook and behave. Our mother said it was too late to teach us any manners.

Dad always said, “Broken bones grow back stronger,” raising us the same way his older brother, Gene, raised him. A father’s job was to control the pace of the world’s wounding; to dole out the pain in slightly bigger doses over time so that his kids would learn not to break under pressure. This is what I think of when I think of my sisters and me growing up: we didn’t get anything for free and we blossomed because of it, blood flowering into bruises, skin thick and ripened under the Sonoran Desert sun.

We rarely cried, knowing tears were a sign of weakness, knowing we’d never catch our father or his brothers wet-eyed. I remember seeing one man cry though—our neighbor, weeping the day his dog, Rocco, died.

You never saw a dog as spastic as Rocco. He made a play for freedom every time her neighbor opened his front door. “Rocco, you shit!” we’d hear him yell. Then the screen door would slam, and the chase would begin.

Rocco would never heel and our neighbor, who had a bad leg, could never catch him. It was dodge-and-go for thirty minutes every time, an entertaining show that my sisters and I watched with glee. We scrambled on top of the swamp cooler and cheered Rocco on, loving the way he sidled in and ducked away at the last second.

The downside to our afternoon pleasure was the finish. The longer it took the neighbor to catch poor Rocco, the harder he would kick him once he got him leashed. “You fat old bastard!” we yelled when he did this.

Rocco’s owner lived alone. He passed us Popsicles through the rip in his front screen door, but only if we would stay with him for a while after eating. Cold and sticky and sweet, the Popsicles were a treat we never had in our own refrigerator, stocked only with its week-old refried beans, lard-hardened cheese enchiladas, and Bud Light beer. When we finished, he’d come out and wash our hands with the hose. Then he would gather us around his lawn chair, take one of us on his lap, and crack stupid jokes. We could not leave because that would mean abandoning whoever he had on his lap. The rest of us gnawed nervously on the Popsicle-sticks until he let the unlucky one go.

“Next time I ain’t taking one of those Popsicles,” we would swear. Then his jalopy would crunch up the driveway and we would see him carrying sacks emblazoned with the words Del Sol Grocery to the carport door. Our mud cakes would fall to the ground. We risked plenty for those Popsicles.

“Don’t go near that guy.” Our parents gave us strict instructions to stay away from him.

Everyone said the only reason he lived in Yuma was because his ex-wife died and left him her house. They said never to trust an Indian who doesn’t want to go back to his own reservation. Their mean comments were rooted in jealousy. He wasn’t an enrolled Quechan (Yuma) tribal citizen, yet he had inherited a house on our reservation.

Property ownership on our ancestral lands became complicated in 1893, when the Colorado Irrigation Company started lobbying the U.S. government to build a diversion dam on our reservation. Suddenly, engineers and Indian agents were advocating for the government to “give” tribal members five acres each and sell the “excess land” to White farmers. Before this era in history, our home at the confluence of the Colorado and Gila Rivers had been mostly ignored by whites, many of whom had assumed southeastern California was sterile. Instead, it was an oasis in the desert, beneficial for planting.

By the time I was born in 1969, it was hard to imagine the sheer size of the Colorado River before it was dammed. For eons it had burst its banks in spring, carrying sediment carved off the walls of the Grand Canyon. There was always snow in the mountains, which meant an annual flood was guaranteed, and every year our ancestors went to higher ground until the water receded. When they came down, they planted in the nitrogen-rich silt deposited by the river: melon, squash, beans, and corn. They rebuilt the previous year’s swales and dams for irrigation, adjusting annually to the new contours of their farmland.

My inheritance should have been a house with abundant crops grown in some of America’s most fertile soil, but despite petitioning Congress, Dad’s great grandparents lost their battle and their land to the U.S. government via termination policies involved the Dawe’s Act. In 1911, purportedly to pay for canal construction and the tribe’s new irrigation costs, the government sold our best farmland for pennies on the dollar. Concrete canals were built for white farmers, cheap wooden ones for us. Maintenance fees resulted in the concrete canals being patrolled and kept in good condition, whereas ours leaked and destroyed the soil with alkalinity.

The 1912 flood was the last time Dad’s great-grandparents planted in the traditional way. By 1914, our family members, Dad’s Quechan grandfather included, received ten acres each (a number that paled in comparison to the average one-hundred-acre allotments on other western Indian reservations). In 1915, the government adopted a rule that Indian agents could lease Quechan land for ten years at a time if it was not being used to their liking, and from that point forward White farmers took over our reservation.

With eighty percent of our original treaty land sold, only three houses had been built by Dad’s family. Dad was the fifth child, and by the time I was born, his mother and two brothers called the houses home. The family had more acreage, but banks would not accept reservation plots as collateral, and even the houses we did have were gained when my grandpa, dad, and the family drove out to San Diego in 1956 to dismantle and transport prefabricated plywood houses that had been built for shipyard workers during the war. Because of this reservation housing scarcity, we lived in duplexes, apartments, and run-down stucco houses, rental properties on both sides of the river. Renting was a common circumstance for many big Quechan families, and therefore many people resented Grandma’s neighbor for his house on the reservation. Grandma herself was Laguna Pueblo, which meant they might have resented her too.

When the rattler got Rocco, our neighbor’s scream ripped the desert. I was hiding behind clothesline sheets in a game of hide-and-seek when I heard him yell the dog’s name. I came out of white cotton to see his shovel moving like a jackhammer as he chopped the rattler in two.

He threw the shovel down and limped over to Rocco. His good leg buckled. We inched closer. Rocco was bleeding out of two puncture wounds and his forehead was starting to swell. “What’re you staring at?” our neighbor yelled.

The rock wasn’t big, and he only threw one. It struck the back of my hand, and my sisters took off running. Stunned by the pain, I lost them. The memory gets lost, too, at this point, but I always say I ran down to the canal. I wouldn’t have gone home while I was crying. My sisters would never let me hear the end of it. And it wasn’t like I feared Dad would whoop me. He wouldn’t have. But even if he said nothing, I knew he’d be disappointed.

Dad had a secret. I could see it in his body and sensed it in the way Mom sometimes told us to leave him alone. I felt it in the air like static when he grew angry at the park, restraining himself, barely, in exchanges with leathery men in gallon hats, men who refused to let us play with their daughters. I had seen Dad knock a guy off his feet with one punch, but he was straightening his life out in my early childhood, and his new docility embarrassed me.

Dad belonged to the desert like a naturally rooted cedar, and the incongruent way he started shrinking small in town was scary. He sometimes had night terrors, jumping to his feet with his fists raised like he didn’t recognize Mom. During my early years in Yuma, he held a river of traumatic events in his body, and if the flood of pain hadn’t finally busted open, I never would have learned his secret myself.

When life grew stressful, and he had trouble sleeping, he always retreated to the land. I don’t know how many times he drove us out to go hiking near Picacho Peak, insisting that it was his job to help us grow strong. Mom always stayed back at the dirt parking lot, at the base of the desert peak, cracking sunflower seeds and reading. I would see her when the trail switched back, shielding her eyes with her book, fidgeting as she watched us climb higher.

The loose gravel was slippery, but Dad refused to carry us, and didn’t like it when we asked to rest. When we tried to sit and scoot down a slippery slope, he barked for us to stand. We would gain elevation gradually until we ran into rock walls. He would say, “wait,” then climb up, and call for us to come closer. He would grab us by our wrists and pull us up the face. Once we were together, we would walk farther until we were on top of the world.

Looking down at our Chevy Nova on the dirt road below, the vein in my neck would pulse, and my head would spin dizzily. The car looked like a toy, and Mom like a small doll waving her arms helplessly, worried to see us so high. The desert reduced Mom, like town did Dad. Out here he was towering, standing at the edge of the cliff, his hair whipping around in his face.

I usually shied away from the precipices, but Dad always came over. Squatting low to look us in the eye, he gave instructions: “If anyone moves from where I put you, you’re going to get a spanking.” Then he would take my older sisters, Joan and Lori, to sit on the edge of the cliff. Monica and I would huddle together hoping to stay where we were, but he always returned for us as well.

He would arrange us two on his right and two on his left with his arms extended across our laps like a safety bar. My legs would dangle heavy and the wind would blow across the sweat at my lower back. Whenever I shivered, feeling frightened, Dad would scoff and roll his eyes. “You’re not going to fall,” he would say, and trusting him, I would manage to relax and see.

The desert stretched on forever, and a green body of water snaked through the mauves and tans.“That’s the Colorado,” Dad told us, using his chin to point at the river in the distance. Our ancestral homeland stretched on as far as the eye could see.

Then Dad would grow quiet. He was always capable of keeping still for long periods of time. Sometimes we complained and pestered him to go home, sometimes he sucked us into the silence and I would lean up against his body and feel the weight of his wounding, as well as the difficulty of my knowledge that not everything was getting told.

—

Deborah Taffa’s memoir, Whiskey Tender, has been named to 2024 best lists at Esquire, Oprah Daily, ELLE, and The Washington Post. With fellowships and grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, PEN America, MacDowell, and the NY State Summer Writers Institute, she received her MFA in creative nonfiction writing in Iowa City. A citizen of the Kwatsaan (Yuma) Nation and Laguna Pueblo, Taffa is the director of the Creative Writing MFA program at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. This essay is an excerpt from the chapters “Animas (1981)” and “Almost Yuman (1972)” as they appear in Taffa’s memoir, Whiskey Tender, (HarperCollins, 2024).