Feet, sandals,and the power of political agency in the ancient southwest

By Jim O’Donnell · Illustrations by Marty Two Bulls Sr.

Eight hundred years ago, something profoundly interesting happened in the American Southwest. Over the course of about one hundred years, the Puebloan world consciously transformed itself from a stratified hierarchical society to a system with no apparent markers of classor status. In our current state of political and climate chaos and anxiety, the experiences of Ancestral Puebloan people teach us that deep societal change is possible.

I returned to Yucca House on a dusty morning in late May, maneuvering my truck down a gravel road lined with abandoned irrigation pipes, pumps, hoses, and sprinklers. I parked past a “No Trespassing” sign, near a windswept farmhouse surrounded by a green lawn. A brown haze of dust, pollen, and smoke from fires hundreds of miles away cloaked Sleeping Ute Mountain and the mesas to the south.

Beyond a creaking metal gate lay the remains of what was once a thriving town, home to hundreds of people. Seven hundred years ago, farmers worked plots of corn, beans, squash, and bright bee plant watered from a bubbling spring. Others fashioned ceramics or tended cooking fires and flocks of turkeys. Laughing children raced through the plaza where dancers celebrated connections of sky, earth, and ancestors.

Then it all came to a bloody end.

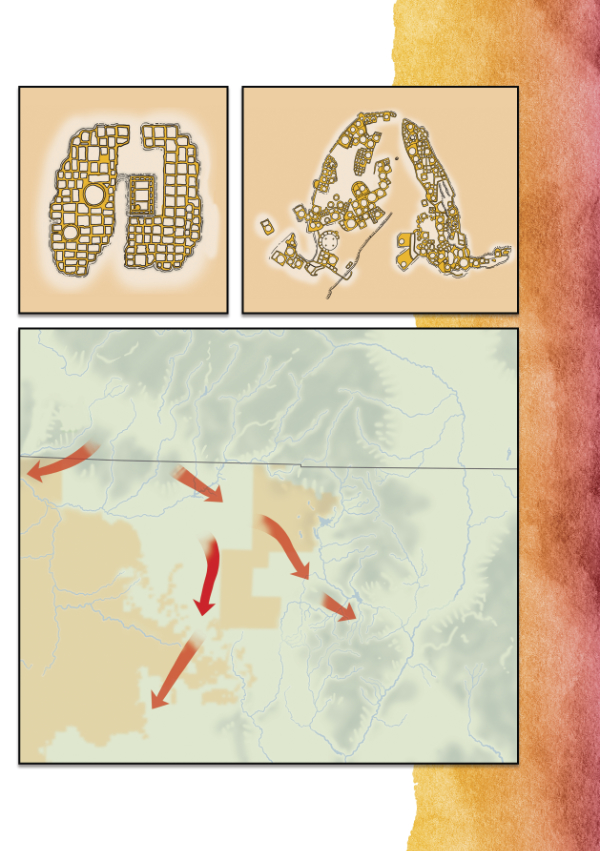

Today, Yucca House is a national monument six miles from Mesa Verde National Park in the southwestern corner of Colorado. Plowed, leveled, and irrigated fields surround mounds of rubble. An astounding number of rattlesnakes inhabit the site. The ancient walls are of coarse sandstone blocks standing in intersecting rows, creating a mesh of rooms that appears like an L-shaped waffle when viewed from above. The wooden roofs and stone towers of the town collapsed centuries ago. Save for the wind, a deep, well-earned silence embraces the ancient settlement.

Yucca House stands out as one of the largest archaeological sites in southwestern Colorado, but more importantly, it is the communal plaza where children once played that makes this place particularly intriguing.

“The layout of the lower plaza and its central public space is dramatically different from those at other Mesa Verde villages from that time,” archaeologist Scott Ortman, author of Winds from the North: Tewa Origins and Historical Anthropology, tells me later. This communal plaza hints that the people of Yucca House may have been experimenting with something profound, a complete reordering of their spiritual lives and the creation of a new socio-economic organization. Something where power seems to have devolved from elites to the common person. Something increasingly focused on the well-being of the entire community. Something more resilient.

And it was that experimentation that may have gotten them into trouble.

In the 1270s, widespread violence engulfed the Mesa Verde region. While Yucca House has never been formally excavated, Richard Wetherill, writing around 1900, noted the remains of dozens of individuals apparently murdered there. At nearby Castle Rock Pueblo, forty-one people were massacred, their remains showing signs of extreme trauma. At Sand Canyon Pueblo, where I worked as a young archaeologist in the late 1980s, dozens of people were apparently killed, and possibly more, given that only about five percent of the site has been excavated. Other Mesa Verde sites likewise bear the remains of victims as well as artistic representations of violence. The collapse of the Mesa Verde system was a very bad time, Ortman says.

It was also an instructive time, something worth considering in our modern world of climate change and political turmoil.

Eventually, the Ancestral Puebloan people of Yucca House and the larger Mesa Verde region up and left. Demographic studies suggest that between the years 1250 and 1290, an estimated 35,000 individuals—the majority of people in the region—migrated south and west. Some went to the Hopi mesas, others to Zuni lands, some to Acoma Pueblo. The largest group, around 15,000 individuals, made their way to the middle Rio Grande Valley of present-day New Mexico. These Ancestral Puebloans, most archaeologists now believe, were the ancestors of today’s Tewa people.

Who brought such violence to the people of Castle Rock, Sand Canyon, and Yucca House? We may never know, but it is possible the perpetrators were the region’s ruling elite, perhaps desperate to cling to power as their world collapsed around them; or perhaps common people seeking change. Most likely, it was part of the back and forth of a complex regional civil war.

The migrations of the Tewa people’s ancestors from Mesa Verde region to the Rio Grande and the creation of a whole new way of life upends much of how historians and archaeologists think about the ancestors of present-day Puebloan people, the value of Indigenous histories, and how pre-Columbian Indigenous nations chose to structure or re-structure their worlds. It places Indigenous experience at the center of self-conscious decision-making. The Ancestral Puebloans were cognizant political actors, shaping their own reality. It also teaches us that deep social change is our birthright as human beings.

Dr. Ben Bellorado points to a series of white boxes lining a table in the Mesa Verde Visitor and Research Center. Each box contains a real sandal once worn by Ancestral Puebloan people of the Mesa Verde region.

“Clothing and representation of clothing tells us a lot about social identities and power structures,” Bellorado says. “And since footwear was usually made of yucca leaves or fibers, it survives better than other types of clothing.”

Social and economic inequality were a part of daily life in the Four Corners region from 800 to 1300. Bellorado studies nearly 8,500 years of footwear traditions from across the region. By far the most prevalent type was the simple yucca sandal. These were easy to manufacture. They wore out quickly but were also easily replaced.

Then there were the twined sandals. These specialized items were made for over 1,500 years beginning around 200. The twined sandals, Bellorado explained, were rare and complex, employing finely woven, pre-made yucca string. They took days, if not weeks, to construct and would have been expensive in terms of both time and material. The twined sandals had both colorful and textured treads that left unique footprints in the sands of the region. They were also uniform in nature, suggesting a regionally shared way of constructing them.

“These were hands down the most complex textile ever made in the American Southwest,” Bellorado says.

It appears that certain communities specialized in the creation of these high-end sandals. The raised treads likely signaled that the wearer was a member of a privileged elite or a political organization, family, or a group in control of vital esoteric knowledge. “You could see these prints in the sand and tell what groups their wearers belonged to based on the tread design,” Bellarado explains.

The size and shape of the sandals suggests they were worn exclusively by adult men during both the Chaco and Mesa Verde eras. Weavers may have been holders of specialized spiritual knowledge, holding positions of prestige and imparting that knowledge into the sandals themselves.

Footprints, apparently, mattered. Twined sandal symbolism turns up in pottery, petroglyphs, plaster murals, and other artworks from across the region. Footprints mattered, perhaps in part, because feet mattered. Or more importantly, toes. Polydactylism is a condition in which a person has more than five fingers or toes on one or both of their hands or feet. In the 800s and 900s, individuals bearing this unique genetic trait appear to have founded a nascent nation-state in the Chaco Canyon region of northwestern New Mexico, with its capital at the bottom of Chaco Canyon itself. Several ornately buried six-toed men were found at Chaco. Recent DNA studies suggest that these individuals were related through the female line and had elite lineage lasting at least 330 years. Interestingly, the six-toe motif shows up in Indigenous Mesoamerican art from the same period, adding to the growing body of evidence of some yet-to-be understood political/religious connection between the northern Southwest and Central America. The greater Chaco political system, often referred to as the “Chaco Phenomenon” appeared soon after the collapse of Teotihuacán in Mexico and the elite of Chaco enjoyed chocolate, copper, and macaws—all products imported from Mesoamerica.

“Think of Chaco as a sort of small Rome,” Ortman tells me. “The center of the world, a place of riches, a place of nobility. Chaco was a place where wealth went in, but it didn’t come back out.”

Probably because it was a tax or tribute. The movement of wealth from the common people to an elite or ruling class.

The fourteen Great Houses at Chaco were “a sink for fancy things,” says Bellorado. One room at Pueblo Bonito, for example, held more turquoise than in the rest of the entire Southwest. In the next room, archaeologists found more jet gemstones than in the rest of the entire Southwest. Other rooms contained macaw skeletons and feathers, flutes, uniquely crafted arrows, carved wooden staffs, and ceramics decorated in ways that were unusual for the region at that time. Finely made shell necklaces, silver, abalone, and conch shells abounded. Small, privileged groups, families, or organizations enjoyed life in finely-built and decorated multi-story Great Houses with large kivas, fancy redware ceramics, and towers. Some archaeologists call these Great Houses “palaces.”

At both Chaco and later at Mesa Verde, Ortman sees evidence of a status competition between families—a sort of Game of Thrones.

“Does this apparent wealth inequality suggest a political hierarchy?” asks Dr. Tim Kohler of Washington State University. “We can’t be one hundred percent sure, but more often than not, they go hand in hand.”

From about 850 to 1150, the Chaco political and economic structure came to dominate the Four Corners region. Besides the Great Houses, Chacoans constructed a system of wide formal roads to facilitate a regional system of tribute. They expanded their power with colonies archaeologists call “outliers,” and they grew social hierarchies of extreme inequality. Indigenous histories of Chaco mention slavery, torture, and weather control. These are sensitive stories and the details are not mine to tell, but it seems that both the Diné and modern Puebloan people agree that Chaco was a place of darkness and sorrow.

Kohler, Ortman, and a team of researchers modeled wealth differences in the Four Corners utilizing Gini coefficients, a commonly used statistical measure of income inequality within a certain population. They found that increased maize production across the Southwest resulted in staggering population growth beginning around 500. Life expectancy likewise increased through this period. Around 900, Gini coefficients skyrocketed, indicating a rapid growth in wealth disparity. Soon after, the first Chacoan Great House appeared.

Interestingly, the work of Kohler and company suggests that, at the time of Chaco’s rise, people generally tolerated this wealth disparity. Still, not everyone was happy with this powerful new polity. Those on the rim of Chacoan influence actively resisted the new hierarchy. Some populations moved north and west to escape Chacoan domination. Others moved east of the continental divide into the Rio Grande basin that would one day become the new homeland or, as the Tewa say, the “middle place.” Still, during its initial rise, Chaco was somehow able to compel social cohesion while suppressing conflict within its sphere. And then it couldn’t.

Authoritarian political systems are inherently fragile. So, too, systems of extreme wealth inequality. In their research, Kohler and his colleagues demonstrate a “significant tendency for periods with high wealth inequality to be followed by periods of high violence.”

Under the weight of internal conflict, political reorganization, and an extended drought, Chaco fell apart around 1150. “The people intentionally dismantled the power of Chaco,” Dr. Bellorado explains. But the elite had to go somewhere, and the remnants of Chaco appear to have moved north to what is now Aztec Ruins National Monument on the Animas River. And yet, Aztec Pueblo didn’t last, perhaps couldn’t last, and those that hung on moved south. Stephen Lekson of the University of Colorado and author of The Chaco Meridian believes the majority of what remained of Chacoan society eventually ended up at Paquimé in Chihuahua and then, perhaps, Culiacán on Mexico’s Pacific coast. Another group hung on in the Mesa Verde region, attempting a new polity centered in the canyon heads of Mesa Verde and the surrounding landscape.

For 150 years after the collapse of the Chacoan state, the people of the Four Corners struggled to make sense of what happened and to figure out what came next.

Around 1080, a curious feature began showing up on the twine sandals. The “toe jog,” a fabric projection where the pinky toe is positioned, appears as if accommodating a sixth toe. These toe jogs coincided with a massive expansion of Great Houses across the region, perhaps signifying an attempted revitalization based around the memory of a Chacoan elite. The toe jog might represent an attempt to tie the present and future to a nearly mythological past.

“It was not unlike current political and religious revitalization movements seen throughout the modern world. It was an attempt at societal renaissance of the reimagined past,” Bellorado says.

Like Castle Rock, Sand Canyon Pueblo may have been yet another attempt at revitalizing the Chacoan legacy, imitating many key architectural and planning features. It was a large, fortified, and carefully laid out town constructed rapidly in the 1240s. In many regards, it is strikingly similar to Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon.

But like Chaco, Sand Canyon was doomed. The end came around 1280. During excavations, archaeologists uncovered a mess of human bones scattered in a way that suggested a battle, followed by a mass killing. Most intriguing was the discovery of the remains of a six-toed male known to archaeologists as Block 100 Man. The depression fracture on his skull indicates he was killed by a harsh blow to the head. Was this man a descendant of the Chacoan ruling clan? It seems likely.

While Sand Canyon may have been an attempt at retaining and reinvigorating the Chacoan legacy, Yucca House seems to have been the opposite. Originally a Chacoan outlier, the people of Yucca House began transforming the town’s layout around 1200, opening the communal plaza and lessening indicators of hierarchy.

Amid what may have been a regional civil war, mass socio-cultural experimentation was underway across the region. Their world turned upside down, Ancestral Puebloans scrambled for something new.

The post-Chacoan revitalization movement lasted right up until the 1260s when both toe jogs and twined sandals suddenly disappeared. In fact, production of all types of sandals— simple and complex—essentially ceased by 1350 and there is no evidence that anyone in the northern Southwest made or wore sandals again. Instead, they were replaced with simple leather moccasins that all looked generally the same. When it came to footwear, you could no longer distinguish one person or group from the next—and this was probably true with other forms of clothing. Simultaneously, architectural forms simplified and became uniform. The status of one household or another could no longer be visibly distinguished. So too with ceramics. The intricate designs that had characterized Ancestral Puebloan pottery in the Mesa Verde region for centuries were no longer made. Instead, the narrower range of design structures and systems developed in the Rio Grande Basin took hold. It is as if a whole social structure that had once dominated Chaco, Mesa Verde, and the San Juan Basin was deliberately rejected and remade.

This type of conscious break with either the past or other cultures is known as schismogenesis, a way one group or culture defines themselves in opposition to their neighbors—or their past. In this case, the Tewa people consciously created a new society in direct opposition to the one they had lived under for centuries.

Clearly, something big was happening but it had yet to reach its conclusion.

The economy of the greater Mesa Verde polity of the late 1100s and 1200s centered on the family unit, with each family economically self-sufficient while possibly offering goods and labor to their rulers. Markets, it seems, did not exist; there was little incentive to grow surplus food and there was no method to redistribute surplus—except up, as tribute. As the population expanded, families farmed increasingly marginal areas, wild game such as mule deer were hunted out and the gulf between the haves and the have-nots widened.

To further complicate matters, the people of Mesa Verde became overly dependent on maize for their diet. Some studies estimate that by the early 1200s maize made up around eighty percent of the caloric intake in the region. As wildlife populations collapsed, the people of Mesa Verde began raising turkeys for meat, feeding them with, yes, maize. The entire food system became a house of cards built around a single source.

And to make things worse, tree-ring data indicate that around the year 1000, a remarkable climactic shift began. For centuries, the American Southwest had enjoyed relatively cool and wet El Niño-like conditions. Then, during the height of Chaco, a La Niña pattern took hold, not every year but more often than not. By 1200, hot and dry conditions dominated the region. Interestingly, around the same time the city of Cahokia along the Mississippi River near present day St. Louis also crumbled, burdened itself by inequality, hierarchy, and climatic shift.

Michelle Hegmon, an archaeologist at Arizona State University’s School of Human Evolution and Social Change believes it was not so much the drought that took down Mesa Verde. After all, Ancestral Puebloans were skilled at managing the vagaries of the Southwest’s mercurial climate and had weathered much worse climactic shifts. Rather, it was the social reaction, or lack of reaction, to the drought that ultimately tore things apart. According the Hegmon, the culture of Mesa Verde was deeply conservative and hierarchical, perhaps still clinging to the old Chacoan habits. As the climate warmed and dried, corn production dropped off dramatically, the ruling elite failed to react. Malnutrition set in, then starvation, then violence.

“They were very established in their ways,” Hegmon tells me. In other words, they were culturally stuck. Clinging too rigidly to traditional ways rendered them unable to deal with a new reality.

“They didn’t all have to leave,” Ortman says. “Even during that big drought, the land could have supported most of those people.”

The fact is, they chose to leave.

Archaeology allows us to reflect on present cultural and socio-economic choices by holding the mirror of the past to our gaze. But only if we pay attention to the evidence.

The fundamental weakness of sweeping, popular historical narratives such as those written by Steven Pinker, Jared Diamond, and Yuval Harari is that they ignore human agency, instead relying on environmental determinism and teleological thinking. These writers ignore more than two hundred years of accumulated archaeological evidence that would otherwise undermine the foundations of their books. As a result, these works reproduce the limiting anti-historical mythologies we were taught in school and leave out the human ability to make choices.

The human experience has never been linear. There was never a stage of human history when all humans survived in tiny egalitarian bands of hunter-gatherers and there was never one single “Agricultural Revolution.” Over the past 500,000 years, human beings have created a beautiful and bewildering array of social, political, economic, and spiritual systems. Humans have always had the ability to make informed choices. Viewing history this way offers us a far more interesting set of stories than the overly simplistic and frequently racist histories we have grown up with when it comes to Indigenous America.

Moving from a top-down and weak hierarchical system to a peaceful and resilient social structure bordering on the egalitarian, the Ancestral Puebloan experience demonstrates that we are not obliged to stick with structures that no longer serve us. Climatic changes may influence options available but at the end of the day, people make informed and conscious choices as to how they respond to challenges they face.

We do need to be careful here. Far too often, the past is viewed through the lens of the present. In the violence-wracked decades of the early twentieth century, archaeologists understood most Ancestral Puebloan architecture as defensive in nature. During the heyday of environmentalism of the 1960s and ’70s, ancient human societies were viewed as subjects dominated by the whims of regional environments and weather patterns with observed failings emanating from a perceived misuse of natural resources. Likewise, in our current state of dramatic income and power inequality it can be tempting to view the entirety of history simply as a product of the struggle between the haves and have-nots. But human beings are far more complex than that and even though current evidence points to a bloody competition between classes in the ancient Southwest and the birth of a creatively imagined future, we nonetheless need to remain aware of our biases and how they impact our thinking and interpretations.

As Stephen Lekson puts it, the ancestors of the Tewa voted with their feet.

Sometime around 1200, the ancestors of the Tewa began looking for other options. People travelled regularly into present day New Mexico, specifically to the Jemez Mountains. It takes about two weeks for the average adult to walk the 250 miles from Mesa Verde. What were initially trading journeys among familiar neighbors grew to something more. These people were scouting a new homeland.

“The decision to pick up family and move was not taken lightly,” says Dr. Matthew Martinez, executive director of the Mesa Prieta Petroglyph Project, and former lieutenant governor of Ohkay Owingeh, one of New Mexico’s six Tewa Pueblos. “Our ancestors took the time and put a lot of thought and consideration into their choice. The movement from Mesa Verde to the upper Rio Grande was meticulous.”

Archaeological evidence supports this.

For centuries, the people of Chaco and Mesa Verde regions had obtained obsidian—a volcanic glass—from a wide range of sources throughout the Southwest and beyond. Even though Indigenous tool makers preferred harder materials such as cherts or quartzites, obsidian was often utilized in the manufacture of tools such as scrapers and projectile points. After Chaco, the Mesa Verdeans imported obsidian almost exclusively from New Mexico’s Pajarito Plateau in the Jemez Mountains. Imports grew as Mesa Verde’s population declined in the 1200s then ceased completely as the people moved wholesale into New Mexico and Arizona.

Both Ortman and Bellorado theorize that the obsidian traders were less interested in the volcanic glass for tools, seeing its value more in the significance it carried. Most obsidian collections from the Mesa Verde region comprised small flakes, not tools.

In many Puebloan belief systems, mountains represent the physical connection and interaction between the earth and the spiritual world. They are sacred places, closer to the deities that control the weather. Summer rain storms form over the high country and springs that become great rivers are born in the mountains. Obsidian, a Tewa friend tells me, was believed to have been created by lightning striking the ground.

“It seems almost like they’re trying to get the glassy black material because of its color and association with the mountains and lightning or rain deities,” Bellorado says.

This suggests two things. First, that the people of Mesa Verde had strong connections with the northern Rio Grande prior to migration and two, that the initial migration was indeed a slow, methodical process of preparing the destination for the mass of people that would soon arrive.

“They’d learned their lessons,” Martinez says. “And they were ready for a better life.”

To be clear, not all archaeologists are convinced that the modern Tewa are the descendants of the Mesa Verdeans. The debate has, at times, been heated. Still, Ortman and others have accumulated a compelling amount of evidence for this theory from a wide range of disciplines—archaeological, biological, zoological, and linguistic.

One line of inquiry compared turkey bones from both Mesa Verde and the Tewa Basin. These DNA studies suggest that a new, genetically distinct type of turkey appeared on and around the Pajarito Plateau in the late 1200s. The new population of turkeys were different from earlier turkey populations in the region but identical to the birds that had been a source of food and feathers at Mesa Verde.

Linguistically, the Tewa have words that describe architectural forms and features never utilized in the Tewa Basin but that were common in the Mesa Verde region. It is the same with ceramics. Tewa words relating to pottery were clearly born in older words describing woven items or basketry, even though modern Tewa artists do not utilize baskets in their ceramics as did the people of Mesa Verde. These so-called “fossil words” also reference plants, water bodies, and other items that exist in the Mesa Verde region but not the Tewa Basin.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence linking the modern Tewa with Mesa Verde comes from oral histories. The Tewa themselves have numerous stories detailing their migration from the north to the Rio Grande. Stories recorded by anthropologists over one-hundred years ago finds the Tewa using names for places located in southwestern Colorado, places the storytellers had never visited.

“We have many terms for places in the north,” Martinez tells me. “It’s like a story of evolution. We know our people emerged from certain mountain ranges and lakes up north. They went through dark times, struggled, learned, changed, and came south.”

At the core of these stories, Martinez and others tell me, is adaptability and the willingness to change behavior, change government, and “turn over our way of doing things.”

Dismissing Indigenous histories as simple “mythology” ignores a vast historical resource that could answer many so-called archaeological “mysteries,” if done respectfully and under leadership of Indigenous people. It can also help us as a nation reconsider how we handle the challenges we face today.

Ortman received high praise from many Tewa folks for working with them on this research instead of simply extracting information. His research is all the more robust for the effort.

My former mentor Dr. Ricky Lightfoot, at my alma mater Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, tells me they have shifted much of their research to working with and under the guidance of tribal advisors. Lightfoot directed excavations at Crow Canyon for several decades and currently sits on the Board of Trustees. “We’re thinking more in terms of what we can give back to Native communities,” he says. “We’re focusing our research on things that matter most to modern Pueblo people.”

“I’d love to see the academy recognize traditional and Indigenous knowledge systems as the source for information and that our system influence policy, decisions, and research,” Brian Valle, former Governor of Acoma Pueblo says. “We have the responsibility to continue the connection to these places.”

Wind bent the sage and chamisa. I watched my steps, aiming to avoid rattlers. Someone had gathered a handful of ceramic sherds and arranged them in a square atop the sandstone wall. I came across several obsidian flakes and wondered how far they had come to be there in the dust of Yucca House. From the top of the main mound overlooking the townsite, I looked east to Mesa Verde, green against the gray sky. West, Sleeping Ute Mountain lay shrouded in yellowing dust.

One old Tewa story, Dr. Martinez tells me, describes Yucca House in amazing detail, referring to the ancient town as an ancestral home. “It is a place that is still alive for us,” he says.

Former Governor Vallo tells me that each Pueblo has different sensitivities about the power and spirit of Chaco and Mesa Verde and what happened there. “Both of these sites are incredibly important to Pueblo people. What we learned there are lessons still passed on orally and are key to the future of our culture.”

There was never an “abandonment” of Mesa Verde as pop-culture histories insist. Pueblo people simply do not think in those terms. Instead, Ancestral Puebloans seem to have pushed back against oppression and creatively imagined a whole new way of being in the world while simultaneously maintaining connection to ancient homelands and the memory of what they endured.

“We never left,” says Vallo. “We still visit up there. We gather medicines, clay, herbs, and we go to take offerings to those sites. Those sites are still alive. We are still alive.”

An Approximate Timeline of Events

Leading to the Great Ancestral Puebloan Migration

All dates are common era

200

First twined sandals appear in the American Southwest

850

Greater Chacoan political system established in the Four Corners Region

1000

Centuries-long climactic shift begins in North America

1150

Chacoan political system collapses

1080

Toe jog to accommodate six toes appears in twined sandals

1100

Aztec polity established near present day Farmington

1100

Yucca House established six miles from Mesa Verde

1200

Mesa Verdean travelers begin importing obsidian from Jemez Mountains

1200

Yucca House town layout transformation begins

1240

Sand Canyon Pueblo established

1250

Migrations to present-day

Pueblos of Hopi and Acoma, and upper Rio Grande basin Pueblos begin

1270s

Violence at Yucca House, Castle Rock, Sand Canyon, and elsewhere

1280

Sand Canyon Pueblo destroyed

1290

Migrations complete, Four Corners region largely empty

1250–1300

Tewa towns such as Tsankawi, Ohkay Owingeh and P’ohwhogeh Owîngeh established in the northern Rio Grande Basin

1300–1350

Sandal construction ends, Ancestral Puebloans begin wearing moccasins

Jim O’Donnell is the author of Fountain Creek: Big Lessons from a Little River (2024) from Torrey House Press. Learn more at his website.