So Far From Paris or Santa Fe

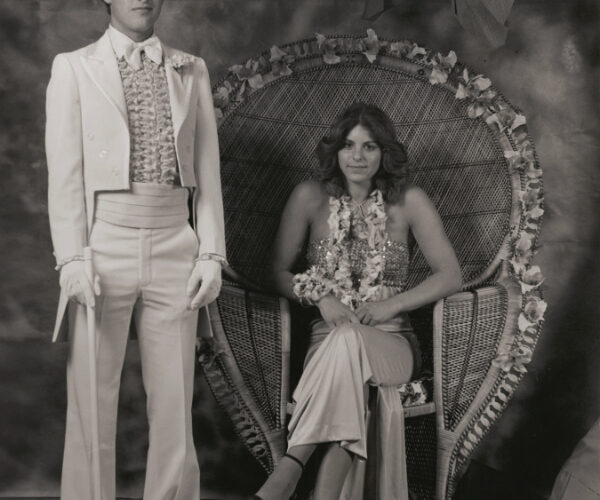

Couple at Prom, Robertson High School, Las Vegas, New Mexico,

1981. Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives

(NMHM/DCA), 164812.

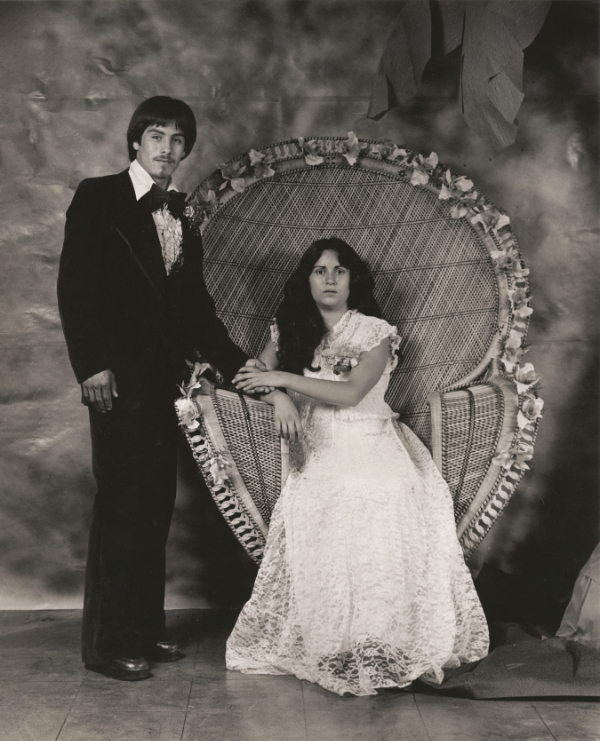

Couple at Prom, Robertson High School, Las Vegas, New Mexico,

1981. Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives

(NMHM/DCA), 164812.

BY SAMANTHA DUNN · PHOTOGRAPHS BY ALEX TRAUBE

Las Vegas, New Mexico. Fifty-four miles east of Santa Fe and worlds away from its golden adobes, art galleries, trustafarians. Across the ragged current of the Pecos River, beyond piñon and juniper to taller Ponderosa pines.

Las Vegas translated means “The Meadows,” and the town spreads in a malachite ribbon of fertile soil. The vast wilderness of the Kit Carson National Forest borders Vegas on the north; to the south and east the Llano Estacado yawns wide and empty all the way into Texas.

But in 1980 when you said “Vegas,” you really meant Monte Carlos with swivel bucket seats and chrome rims. You meant bronc riders and black tar heroin, Penitentes and La Raza Unida. You meant the United World College up at Montezuma and the state mental hospital along the way. The Old Santa Fe Railroad, roasted cabrito, Joe’s Ringside Bar, and the Plaza Hotel.

Vegas had a reputation.

“Vegas? You’re moving to Vegas? You, güerita?”

Pepper Griego sat next to me in eighth-grade homeroom at Capshaw Junior High. I’d just told her my family was leaving Santa Fe next month for Vegas. What I didn’t say was my single mother went bankrupt and we were getting evicted from our home in El Dorado.

Pepper, short and curly headed, always boasted, half serious, that she was the only Mexican in Santa Fe. Everybody else bragged like they were direct descendants of Don Diego de Vargas, puro sangre all the way to Spain. To which Pepper, Mexican by way of Michoacán, would say, “Pendejos. As if.”

Pepper leaned close to me. “Listen, even I would have a hard time in Vegas with the cholitas. You. Are. Going. To. Get. Killed. We gotta get your Spanish a whole lot better, but I don’t even know if that will help.”

She shook her head.

“Vegas. Híjole. Vegas.”

Soon enough, my mom, grandmother and I unpacked the U-Haul at a rough-looking stucco on a dirt road by McAllister Lake, with a lawn of rusted cars and weeds growing waist high. Then we were landing briefly at a rat trap perched off NM-65, where the busted septic tank spilled our stinking shame onto the road. It was a relief when we finally set up house in a single-wide at Lot 78 of the Enchanted Hills Mobile Home Park. That’s another, longer story, but for these purposes, thank god Pepper got it wrong. Not about the Spanish, she was right, I had to learn it better than Santa Fe required, but I didn’t get killed. In fact, I thrived in Vegas.

Well, mostly. The cholas waited in the school bathrooms, their eyes warning they could strike if they chose to. Then there were the drunk men Mom brought home from happy hour at El Rialto, but my reflexes were quick. On the bright side, I learned that the green chile enchiladas and an order of sopa-pillas at Charlie’s Spic & Span would cure any ill of body or soul.

Anyway, we’re skipping to the part where I, now junior class president at Robertson High School, am considering the ice-pink polyester sateen prom dress my mother and grandmother had driven all the way to the DeVargas Mall in Santa Fe to procure at JC Penney—or rather “Jacques Penné,” the preferred pronunciation in our house.

To accomplish this, two adult women had to drive 108 miles round trip in a rusting Ford Esquire station wagon that doubled to haul my horse’s hay and grain back from Farmway Feed. Alfalfa stalks poked through the back seats, permanently embedded in the blue vinyl. Dog hair, dust and hay swirled in a funnel cloud when anybody rolled down the windows. We kept Allerest in the car for when the cloud kicked up my allergies.

My mom called our car Mariah, after the old song “They Call the Wind Mariah” by The Sons of the Pioneers. Today, the name “Mariah” might bring to mind pop singer Mariah Carey, but she wasn’t around in those days, and even if she were, nobody would have heard her music on our local radio station. KFUN—which everybody just called “Que Fun”—played a mixture of country music, ’70s rock, and, strangely, a little Billy Joel, until it switched to Spanish programming after lunch, the cries of mariachis ringing through the afternoon.

But back to the dress: The flouncy peasant-cut top and the elastic waistband weren’t doing my Rubenesque silhouette any favors. I looked like a bowl of strawberry sherbet.

The real problem was my skin. Parents today will take their kid to dermatologists or order Proactiv on the infomercials, but then, and maybe still for kids who live in places such as I, what Clearasil couldn’t cure, CoverGirl would have to do.

Mom and Gram worked in tandem to apply foundation and false eyelashes, the only time I can remember them doing anything in harmony. Maybe that was thanks to the fact they knew the stakes were high. Their girl had a prom date with a boy, one they knew was too beautiful for me.

The day this beautiful senior asked me to prom goes down as one of the biggest surprises in the history of the world. Or at least in my life.

I was secretly in love with my neighbor Enrique three trailers up, but he only seemed to want to seek shelter at my place when his football star older brother was on a rampage, or to talk to my grandmother about old movies. He would never think to ask me anywhere, least of all a dance, so I assumed going with a fellow junior would be my fate. It was a week until prom and no one else expressed any interest, even though I was the class president and the theme that year was my idea: “An Evening in Paris.”

The fellow junior didn’t seem in much of a hurry to ask, being that he’d only smiled at me in the hall between classes. Let’s call him Jeremiah, a 4-H member, Wrangler-jeans wearer, brass belt-buckle owner, a tall, big-eared, skinny, nice but not terribly attractive kid, like me. That is to say white, Anglo, güero, or gringo, depending on who was doing the describing.

In Vegas, sometimes you didn’t need to call anybody anything to have the snot knocked clear out of you. Just being who you were was enough. This is what Pepper had been talking about—it was a small town where it was tough to be anyone who fell outside the prescribed ways of being.

Not only was I strawberry blonde—aided by Sun-In, a spray-in hair lightener that gave my hair the color and texture of oat hay—I was five foot eight, which is to say gargantuan. And my home was in a park where single-wide trailers lined up like saltine boxes.

My strategy for overcoming this was to join every conceivable school group that would have me—the Ski Club, the pep squad, student council, the student newspaper, the yearbook, the three-member French Club and even the track team, because although I had no perceivable athletic ability, I was big enough to throw a discus. My eventual election as class president was not so much a triumph of popularity as desperation. Nobody else wanted the job.

This is the girl a certain yearbook photographer I will call Joaquin Ortega approached at the lockers. Joaquin was my height but a good twenty pounds lighter. His hair was the rich shade of a coffee bean, his eyes the green of new grass, his lips thin, his nose straight, his cheekbones high. Skin, unblemished. It was easy to imagine his ancestors in the courts of Spain, perhaps confidants of Queen Isabella. If Joaquin had lived in Los Angeles he would have been “discovered,” his likeness put on billboards to sell designer ties or cologne, but in Las Vegas, he seemed almost delicate, neither cowboy, jock, nor vato enough to categorize, and so you rarely found him hanging with a crowd. I occasionally saw him talking to Enrique in the hallways, but I thought of him like a reclusive, rare bird; you might catch a glimpse of color and form, but nothing that could be held.

“How’s it going?” I remember he said, but I was too startled seeing the beautiful Joaquin standing by my locker to reply. He had never actually spoken to me before, even though we’d both been part of the yearbook staff.

The verb “to go” was the cornerstone of our teenage language. We used some conjugation of it in nearly every sentence, usually as a substitute for “say” or “said,” particularly when reporting events or transactions. For example:

He goes to me, “Are you going to the prom?”

And I go, “Like, yeah, I kind of have to because I’m class president.”

And then he goes, “So, you going with anybody yet?”

I go, “Not yet.”

So he goes all quiet, and then he goes, “Want to go with me?”

When I nod he goes, “Cool. I’ll call you later.”

As I recall that’s pretty much how it went, being asked to the prom by Joaquin. I think I held my breath, not entirely convinced that the elusive Joaquin Ortega had asked me to be his prom date. Maybe he had mistaken me for someone else, or maybe he had actually been asking if my good friend, the far cuter Cindy Perez, had a date. I thought it was likely he would come back and say, “Sorry for the confusion,” or “That was just a misunderstanding.”

But he didn’t.

In fact, on Saturday he called and asked if I wanted to help him wash his car. (Getting my number was easy—we were the only Dunns in the phonebook.) I don’t remember much of that day, except that the sky was a blue that seems only to exist in New Mexico, and that the interior of his car was navy fabric that felt like velour as I ran the vacuum over it.

He had a good sense of humor when he spoke, which wasn’t often, and I think I laughed more than I expected. He surprised me once by spraying me with the garden hose, pretending at first that it was by accident but then copped to doing it on purpose. I suppose I threw a soapy sponge in retaliation. Songs by Journey, Foreigner, and REO Speedwagon blared from the speakers of his Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme.

When he dropped me home in the now-shining Cutlass, he acted every inch the gentleman, holding the door for me and coming to the porch to meet Gram. He shook her hand, which she said was evidence of good breeding. Mom stuck her head through the screen door and said, “Hi there cutie,” like she did to anyone handsome. When his car pulled away and I could no longer see the taillights I’d Windexed to a glimmer, Mom shrugged.

“He’s pretty,” she said, cigarette in hand. “Betcha he’s queer.”

Why would my mom say that? Never mind that John Wayne and Charles Bronson movies had formed her idea of how a man should look and act. More likely it was her way of trying to protect me, as in, “Don’t get your hopes up sweetheart. A good-looking guy like that is not going to fall for a girl like you.”

I thought about her words all week while I worked with the dozen or so people who’d volunteered to help me transform our gymnasium into the Champs Elyseé. While draping midnight blue and silver streamers over the rafters and building the seven-foot cardboard replicas of the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe, I considered what I knew about Joaquin, which was almost nothing, and what I knew about homosexuality, which was slightly more than nothing. Gay rights had barely entered the national conversation, let alone a distant outpost in what still felt like the Wild West.

During my freshman year there had been a nice senior who had a high-pitched laugh and dressed in silky tops à la John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever. Frequent perms turned his curly hair orange, and he was always talking about going to Albuquerque, the big city. At school he never forgot to give me an “Hola chica,” smiling and joking, but when he walked down the hall a hiss of voices would spit homophobic slurs in Spanish and English. I never thought much about it, because everybody was teased to some degree, but during one summer, news spread that he had committed suicide. The rumor about the way he ended his life left a sick feeling in my stomach: throwing himself off a bridge. Up in the mountains outside of town. Late at night. Without his car nearby.

After that, I understood what people thought of you in a place like this could literally be a matter of life and death. Safer not to give anybody enough information about you to form opinions.

But that still begged the question, what did Joaquin want with me? I wondered if he, like me, had a big plan for the future that meant making a beeline out of Vegas as soon as he had half a reason to go.

From what I could tell, the usual dreams for kids in Vegas were to make it out to Albuquerque, possibly even Denver, perhaps somewhere like Austin. But my dream was crazier: Unknown to anyone, I was living my life according to a manual, which guided my every action. If I did as it directed, it would transform my life the way the fairy godmother’s wand cured Cinderella.

That manual would be Scruples, by Judith Krantz.

All right, so it wasn’t a manual, technically speaking, just a mass-market novel I’d found in one of Mom’s many stacks of paperbacks pressed along the trailer wall, their collective weight like boulders crushing the shag carpet. But the moment I first read the story—on a sick day, home from school—I was sure it had been written for me. I read it until I could recite passages, and I kept it on my nightstand for easy reference.

It was about a heroine, Billy Ikehorn (Billy, which was a boy’s name, not unlike Sam, my name. This I noted immediately). She was an intelligent but tubby and unattractive girl who came from a bitter family (more similarities). But this overweight shell was just the chrysalis; all it takes is a trip to France to release the real Billy. She goes to Paris, and in the process of learning to speak fluent French, learns how to dress and to wear makeup, becomes beautiful. When she comes back to the States, men fall in love with her, but not she with them, and through wits and classy beauty, she becomes famous, rich, trounces the bad guys, meets some gorgeous Italian who is her true love, and has the requisite happy ending.

I thought I had found a blueprint. I thought I knew how things would go. All I had to do was work hard. It was the reason I often sat holed up in my trailer bedroom, on my twin bed with the scratchy polyester, butterfly bedcover. I studied French, did all the extra credit, memorized poems by Apollinaire and mimicked out-of-date conversation cassettes checked out from the school library. I read Mademoiselle, Glamour and Vogue when Mom had enough extra money to splurge, even though it was like reading reports from life on Jupiter. I became prone to using expressions like “mais oui” and “zut, alors!” and was the only kid who would unabashedly greet our French teacher Miss Ortiz in the hallway with a loud, “Bonjour madame!”

So, it was no shock to anyone when it came time for the junior class to plan the prom, I pronounced there would be a Paris theme. Only about six people came to the class meeting anyway. There may have been other suggestions, half-hearted, like “Grecian Gardens,” and perhaps a weak complaint that such a big decision should be put to a vote, but I’m pretty sure I steamrolled over all that. Wasn’t prom about being elegant, about romance, about experiencing a glimmer of the fabulous adult world we would soon enter? What else could deliver that except an evening in Paris?

Joaquin, impeccable and creaseless in his blue tux and a tie, arrived to pick me up in the Cutlass right on time. Except he wasn’t alone—Enrique and two of his girl cousins were in tow, making it not a date but a gaggle of five. Which is to say, from minute one the night didn’t exactly go the way I’d hoped.

In the preceding week I had developed a small, chaste crush on Joaquin and secretly wished that he, thanks to his infinite sensitivity and superior intelligence, would see the latent Billy Ikehorn within me. In my fantasy he would proffer his arm and proudly usher me, in my floating swirl of pink sateen, past the entryway, which recalled the Pont des Beaux Arts over the Seine, and into the gym, metamorphosed into the Jardin de Luxembourg.

At the dance there was no way to stage my pastel flourish of an entrance with Joaquin, who walked ahead, laughing with Enrique at a joke only they shared. The gym had failed to transform into Paris: My bridge over the Seine appeared to be just a plywood riser over blue construction paper taped to the floor. The Arc de Triomphe wouldn’t stay up. And the cardboard Eiffel Tower looked like exactly that. But the streamers were kind of nice, and the twinkle lights dressed the cavernous gym so that it did look slightly more festive than the usual school dance. I considered all this as I sat at one of the tables, watching everyone mill around.

I might have been less disappointed that night had I known that one day I would live in France, and that I would eventually move to Hollywood and attend glittering events, and work for magazines like the ones I used to read, and that I would lose weight and learn a few tricks of the fashionistas and that I would, yes, even find the love of my life. Of course, if I had known all of that then, I would also have foreseen the innumerable failures that went along with France and Hollywood, the divorce and romantic disasters, the pains and illnesses, bankruptcy, betrayals, and deaths of people I loved that would also come along. That prospect likely would have cowed me so much I would have abandoned my Scruples blueprint and stayed in the relative safety of the Enchanted Hills Mobile Home Park. Which means, of course, I would have missed my entire life.

Joaquin and I must have had a token dance; the song “Open Arms” by Journey keeps popping to mind, so maybe that was it. Soon word came that a keg party was raging on the hill next to KFUN and the cruise on Douglas Avenue was hopping, cars bumper to bumper along that drag. Enrique and his cousins wanted to go, and, really, what was there to stay for in this paper Paris?

When we finally pulled up to the trailer, Gram’s reading light shone from the window, a small yellow glow through the curtains.

We’d dropped the other girls off at their house, so it was just Enrique, Joaquin, and me. Joaquin got out to help me out of the back seat and walked me to the porch. As I stood thanking him for the night, he suddenly leaned forward and kissed me squarely on the lips, putting his hand on my shoulder with the stiffness of a mannequin. I was as startled as I’d been the day he approached me at the locker.

When he pulled away, he smiled with what felt like genuine warmth and we looked at each other for a moment, not saying a word. The next day we would go back to our lives, passing in the halls, maybe venturing a “what’s up,” but nothing more. But that night we stood for a moment on the porch, his thin hand still on my shoulder, his green eyes looking into my blue ones. Did we know then that no matter where we eventually ended up, this unforgettable little town would always be in our blood, a haunting in our souls, the iron in our backbones?

The sting of disappointment faded.

“Thanks Sam,” he finally said, sliding into the driver’s seat. “Take care.”

I stood there until the red glow of the Cutlass’s taillights disappeared around the corner and watched as they moved down the road past the Fort Union Drive-In, until I could see nothing but night.

—

Samantha Dunn is the author of the novel Failing Paris and the memoirs Not By Accident: Reconstructing a Careless Life and Faith in Carlos Gomez. A longtime journalist, she is a senior editor for the Southern California News Group and now lives in Orange, California. Find her at www.samanthadunnwriter.com.