In Conversation with the Sea

Cara Romero’s photographic counterpoint to the dominant narrative

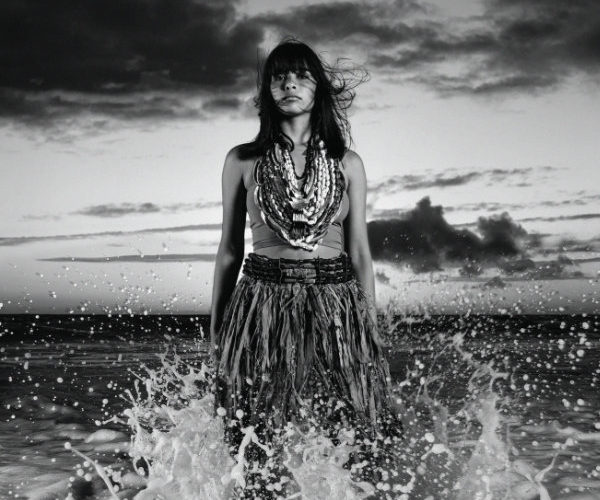

Hermosa, 2021. Archival pigment photograph. 47 ½ × 40 inches. © Cara Romero, courtesy of Gerald Peters Contemporary.

Hermosa, 2021. Archival pigment photograph. 47 ½ × 40 inches. © Cara Romero, courtesy of Gerald Peters Contemporary.

By Emily Withnall

Photographs by Cara Romero

In Cara Romero’s black and white photograph Sand & Stone, Chemehuevi and Diné woman Sheridan Silversmith is embedded in earth. Her head and clasped hands are above the surface of the hard, dry dirt, but the rest of her body is not visible. Silversmith’s gaze is powerful. She is not trapped or buried; she seems to draw strength from the earth. In another black and white photograph, Hermosa, Romero’s daughter Crickett wears a grass skirt and thick seashell necklaces. Crickett stands in the ocean with dark clouds behind her as frothing sea water rises around her. The image is a direct interpretation of the Chemehuevi Creator, Great Ocean Woman (Hutsipamamow). Sand & Stone and Hermosa are both testaments to the inseparability of the Mojave Desert from the first peoples who inhabited this landscape long before colonization—and continue to inhabit it still.

Chemehuevi resilience is a theme also evident in Romero’s photographic series, Jackrabbit, Cottontail, & Spirit of the Desert, which was showcased on billboards in Coachella Valley in 2019 as a part of the Desert X Biennial. The installation featured Romero’s four nephews, who wore Ray-Ban sunglasses and traditional feather bundles on their heads. In Evolvers, one photograph in the series, the young boys run barefoot on the dry earth surrounded by the giant wind turbines near Palm Springs. Their feather bundles mimic both the shape of the turbine’s blades and the shape of the mountains behind them. In other photographs in the series, the feather bundles mimic the shapes of palm trees and yucca plants. Referred to as “time travelers” in the series description, it is clear that these little boys are of the desert: past, present, and future. As Sand & Stone reminds viewers of Chemehuevi creation and inseparability from the earth, Evolvers says: “We’re still here.”

When I spoke with Cara Romero in April, she was at work on her most recent installation project in Southern California for the NDN Collective’s Radical Imagination grant. She has lived and worked in Santa Fe for twenty years, but Romero grew up bouncing between her father’s home on the Chemehuevi Reservation in the Mojave Desert and her mother’s home in Houston, Texas. Her mom is Anglo, and Romero is quick to tell me that she identifies as mixed-race—an identity that can make it hard to feel like she fits in anywhere. “I am a Chemehuevi photographer, but it can sometimes feel a little bit like people are just interested in me being Native,” Romero says.

Normally, she’d leave her husband, Cochiti ceramics artist Diego Romero, and their kids at home in Santa Fe to make trips back and forth for a big project. But the pandemic reshaped Romero’s plans in the spring: She decided to move her whole family to the beach for a few months while she worked. The grant allowed her to once again purchase billboard space in Southern California, but this time the billboards feature photographs of the Gabrielino-Tongva people, the first peoples of Los Angeles, across the LA cityscape. This project is a part of a larger body of work that includes photographs of other tribes native to Southern California, including the Ajachmem, Chumash, Tataviam, and Chemehuevi people, as well as personal work with her family.

The Tongva, like over fifty-five other tribes across California, are not federally recognized and have no land base. “There are modern struggles that go along with being Southern Californian first peoples—we experience a lot of invisibility and persecution,” Romero says.

The project is her way of acknowledging the ancestral homelands of many different tribes whose people are still very much present. “A lot of people don’t know that Los Angeles was the place of origin not only for the Tongva, but for all of the desert people long before it was ever settled by non-Native people.”

Romero didn’t pick up a camera until she was 20. She majored in anthropology at the University of Houston, partly because she couldn’t figure out what interested her and partly because the anthropology department included Native studies. Disillusioned by what she describes as an “incredible paucity of contemporary lived experience” in Native coursework, Romero thought she might use her degree to write new textbooks.

“I can remember always being so disappointed in the Native American history section, whether it was second grade at Thanksgiving or a fourth-grade mission project and all the way up through high school and into college,” she says. “I’m not really a writer though, so I thought maybe I would be a teacher, but I’m not really scholarly either.”

When she picked up her camera her senior year of college, however, Romero knew she had found her calling. With the mentorship of her instructor, Bill Thomas, she learned to shoot and develop silver gelatins. When he saw her talent for storytelling, he encouraged her to pursue content over technical skill. When she shot a series of a friend who had HIV, Thomas was moved, and the series became a part of a campaign to inspire compassion and awareness around HIV/AIDS. “That was it for me,” Romero says. “My whole purpose after that was to pursue photo documentary and photojournalism of Native peoples.”

Romero went on to pursue an associate’s degree in photography from the Institute of American Indian Arts and an applied science degree in photography technology at Oklahoma State University, where she moved into digital work. She describes her current work as an amalgamation of her background in film and her commercial training in digital photography. In her early days as a photographer, Romero says she and other Native students emulated the style of Edward S. Curtis, whose photographs were viewed as canonical to Native American photography. As Curtis had done, Romero shot in black and white, used sepia tones, and had friends pose in their regalia without any evidence of contemporary life.

This period in Romero’s trajectory was short-lived. When her “aha moment” arrived, Romero knew her primary audience needed to be other Native people. “We are functional modern human beings simultaneous to our incredible cultures, and we exist against all odds,” she says.

Romero’s work breaks down the boxes Indigenous people have been placed in by outsiders for centuries. Her sepia-toned TV Indians is a direct response to Curtis. In the image, five Pueblo people stand in a New Mexico landscape in front of a pile of old, clunky television sets. The TV screens depict a range of outdated and stereotypical images of Native peoples, from the Iron Eyes Cody to Tonto and Lone Ranger. The contrast between the Pueblo people and the images on the screens reveals how ludicrous the old stereotypes are.

This year, a new color version of TV Indians was printed for Alcoves 20/20 #4 at the New Mexico Museum of Art, which was on display through Summer 2021. In color, the photograph offers an even more striking contrast between the ways Indigenous peoples have been represented and the ways they actually look. In an online presentation Romero gave for Alcoves 20/20, she sits in front of a background of Mojave cholla. Her dark hair is long and she has bangs. She wears a plaid shirt, big plastic glasses, and long silver earrings. Even in the digital realm, the background of her beloved desert landscape reminds viewers of her deep connection to place.

“We are very culturally private, and it’s very uncomfortable to ask somebody, ‘Hey, can I go on your reservation and take a photograph of you doing anything,’” Romero says. “That’s when your camera becomes like a weapon. It’s been used against Native peoples for a really long time.”

For her, shooting ethically is about responsibility and respect for the people she is photographing. “I’ve always been trying to solve the problem of how to Indigenize this medium that I love so much so that it’s never taking from my community,” she says. “How can I be of service with this skill that I’ve acquired? I really come from that space of service to my community.”

Problem-solving is a part of Romero’s entire process, from start to finish. As a mother with three kids at home, she no longer has the luxury of walking around to find photos or immersing herself in a community for months at a time like many photojournalists do. “There was a time where I didn’t think I was going to get to make art and be a mom,” Romero says.

What she discovered, however, is that by turning to staged productions, she could do a lot of the dreaming and planning in her head while she folded clothes and washed the dishes. “The style that emerged was really a product of my environment,” Romero says. “They’re theatrical because I’m spending a lot of time in my mind and in my sketchbook daydreaming while I’m doing other, motherly tasks.”

When it’s time for the big shoot, her husband, Diego, takes care of all her normal responsibilities at home for the duration of her production. Shooting digitally also makes it easier for Romero to juggle her responsibilities, enabling her to work on postproduction when her kids are sleeping.

Romero says a typical photograph takes roughly three weeks to fully execute, but many can take longer. “All of my photographs start from an in-depth interview process,” Romero says. For her NDN Collective grant project, she interviewed elders, artists, scholars, and activists for two months before she started shooting. Interviews are Romero’s way of discovering what universal themes come up in the community and what stories people want to tell. “Sometimes I have an idea and I talk to them about it—and sometimes the idea comes from the person, and there’s this editorial aspect to it,” Romero says. “We’ll sit down for hours and hours and just talk about life, things that are important to the person, and then I’ll show them sketches of my ideas and let them pick a direction.”

Following the production, Romero shows her models the photographs to “make sure they’re happy with being immortalized.” In her efforts to repair the harm caused by photography in the past, Romero is focused on ensuring that her models’ representation is accurate and comfortable to them. “I really make an effort to ask, ‘Do you love it? Does your grandma love it? Do you want copies?’” says Romero. “It’s a compliment for me when people want copies.”

Not only does Romero give her models plenty of copies, but she pays them, too. “That’s been something that was always really important to me to not capture the exploitative nature of photography and to give back to my community. I always pay my models,” she says.

Romero mostly photographs her friends and family members, and she most enjoys the shared creation they engage in when she begins production. “I like getting up before sunrise and driving out to one of my spots in the desert with one of my dear friends at 4:30 in the morning,” she says. As they wait for the sun to come up, they talk about ideas and the plan for the shoot.

Collections of the Hood Museum and Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

“There’s something about the process and holding space for art that’s really, to me, a magical space of connection,” Romero says. “You’re talking about things that you wouldn’t normally talk about, and you’re sharing space and sacred time together. It’s like playing dress-up and playing imagination when you’re a kid.”

In addition to producing photos in the desert, Romero serves as the director of the Indigeneity Program at Bioneers, a Santa Fe-based nonprofit dedicated to finding solutions to environmental and social issues. She admits that her photography career has become successful enough that she could have stepped away from her role there, but she is committed to Bioneers’ important work. Romero runs the Indigenous Forum, an annual conference dedicated to environmental, Indigenous, and social justice issues, and she’s currently working on a project to create a methodology for tribes to adopt the rights of nature into their tribal governance.

“What that looks like is creating amendments or ordinances within tribal governments that reflect that nature is alive and deserves protection, and that we’re interdependent on our ecosystem,” Romero says. “A lot of tribes have colonial constitutions, so we’re looking at ways to incorporate this language of rights of nature. That work is really inspiring.”

Romero is also inspired by Bioneers’ work with traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), which is an interest she’s held since childhood. TEK involves sustaining traditional arts, medicines, and foods in a way that supports a tribe’s culture and the ecosystem it depends upon. “To be able to make abalone jewelry, the abalone ecosystem has to be healthy,” Romero says.

Bioneers’ influence on her work is particularly evident in her photograph Oil Boom, which depicts an Indigenous man submerged in brown water with pump jacks positioned above ground. And although it’s more subtle, in Water Memory, two Indigenous women float in teal-colored water, dressed in their full regalia—a reference to both the construction of the Parker Dam in 1934, which submerged her ancestral homelands under Lake Havasu, and to rising sea levels.

Collections of the Autry Museum, Crocker Art Museum, Nelson‑Atkins Museum, Museum of World Cultures (Rotterdam), and Palm Springs Art Museum.

Additionally, TEK appears in many of the photographs in her First American Girl series. In this series, Romero does not break down boxes, but rather, she constructs them—on her terms. She constructs the life-sized doll boxes herself, and then works with a model to assemble the precise regalia and accessories specific to a particular tribe. The series began as a response to the dearth of accurate representation in dolls and figurines. Naomi features a contemporary Northern Chumash woman dressed in her tribe’s traditional clothing and surrounded by pine cone shapes and bristle pine cones, which are central to Naomi’s culture. The Northern Chumash are located in California and the doll box’s hot pink background and pinecone checkerboard border is a nod to the state’s skater and MTV cultures. “Naomi in particular has so much about the Indigenous science of California in it,” Romero says. “In my work I try to show that we really need to focus on our ability to continue to not only preserve, but revitalize, these arts.”

Collections of the Museum of Modern Art (NYC), Museum of World Cultures (Rotterdam), and Nelson‑Atkins Museum.

Romero’s First American Girl series began with Wakeah in 2015. “Most dolls that you do find that are Native American are Plains Indian,” Romero says, “but they still get those wrong. And so Wakeah was really an attempt to own the representation and say, ‘If you’re going to do Plains Indian, it needs to be accurate.’” Wakeah is dressed in intricately beaded regalia of primarily white and red. She stands in a teal box with a black border and has her real-life accessories surrounding her, which include a backup pair of beaded moccasins.

Wakeah earned a ribbon at the Heard Indian Market in Phoenix later the same year. Then, in 2019, following a panel on matriarchy that she participated in at Indian Market, Romero met Helen Kornblum.

“The first time she showed up to my studio, she bought her own coffee and scones—and I was like, ‘I love you,’” Romero remembers. Kornblum was 80 and Romero had no idea who she was. “She kind of became like my adopted grandma,” says Romero. As they talked, Romero learned that Kornblum was a psychotherapist and had been collecting the work of women photographers for 60 years. “I had no idea she was an epic serious collector, and she wanted Wakeah and TV Indians for herself,” Romero says. “Then, after establishing this relationship, she dropped the MoMA bomb on me.”

At 82, Kornblum decided to submit 100 different photographs from her private collection to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, including Wakeah. MoMA curators ultimately selected Wakeah to include in the museum’s collection. Romero plans to attend the photo’s unveiling in the spring of 2022. “I could never have imagined. I think I cried a couple of times,” she says. “I really give Helen so much credit for being such a visionary.”

Kornblum has inspired Romero to begin her own art collection. She hopes that like Kornblum, she can make a difference in how museums represent women and Native artists. Romero has also been working as a consultant with three different museums to help correct issues with representation. Romero says, “Now, I have some kind of privilege that I can share.”

Most of the people who collect Romero’s work are women, and it’s not hard to see why. Her photographs of women are informed by Chemehuevi culture. “Chemehuevi women are taught to be strong and speak up and take up space and be protectors,” Romero says. In some of her photographs, such as Coyote Tales and Sheridan, the women look directly at the camera with confidence and strength. In other photographs, such as Kaa, TY, and Jenna, the women are each tuned into an inner reflection of strength, unconcerned by the viewer’s gaze. “It’s the opposite of objectification or voyeurism. It comes from a really maternal place, and a place of empowerment,” Romero says.

David Titterington, who has been teaching Romero’s work for five years at Haskell University in Lawrence, Kansas, says his classes are mostly comprised of women who really respond to her work. “We have a lot of single mothers and a lot of students from reservations just like hers,” he says. “There’s always this immediate recognition of the themes and landscapes and the bodies.”

Although Romero’s work does not overtly engage with the epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW), she is focused on creating empowerment and humanity in her depictions of women. “The idea that we’re not human, or that we don’t exist, or the racist mascots and stereotypes make us invisible and othered,” Romero says. “I think those are part of the systemic reasons why young Native women go missing.” When Indigenous people have been written out of history books, or do not receive federal recognition—like the Tongva she has recently photographed—it’s hard to gain traction on the MMIW epidemic. “These women are real and loved,” Romero says. “I hope that that message comes through in my work.”

Collections of the Autry Museum, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Palm Springs Art Museum,

and Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

Ultimately, love is Romero’s motivating force in creating her photographs, and is one reason she suspects many women connect with her work. “I really love the people that I photograph,” she says. “I’m trying to communicate that love and connection to other people, so I like it when people can feel the emotion from my work.”

When I spoke to her again three weeks later, Romero had been hard at work on her installation project and had given a variety of presentations at institutions around the country. “I have a collection of hoodies from all the colleges I get to lecture at,” she laughs. Her photographs, with their deep colors and powerful Native people, inspire conversation and the need to look and look again. Her work also appears alongside a lesson plan in PBS’s Craft in America “Identity” episode.

Romero has carried her early photography mentor’s legacy forward, and encourages students to focus more on content than aesthetics. “She inspires students and is able to awaken the inner artists in the students in a way that it’s very uncommon,” says Titterington.

Carlos Rivera Santana of the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, says the majority of his students are people of color who often struggle with gruesome histories. “Cara’s work has this way of processing it in a way that it’s not all horrible, but life-affirming, identity-affirming, people-affirming,” he says.

In the end, Romero’s photographs are new versions of the textbooks she wanted to rewrite when she was 20. “I am able to teach about environmental issues, social justice issues, representation issues, and problems with Curtis photographs,” Romero says. “It’s such an honor to have circumvented the system and figured out how to do it with what I was gifted at. I wasn’t gifted at the other stuff, but I desperately did want to teach people.”

Romero has discovered that photographs can often engage students far more than other mediums can, and she’s often surprised and moved by the emotional responses her work can evoke in others. An idea that’s nuanced or groundbreaking can often feel risky, but Romero has discovered that it’s the risky ideas that often resonate the most. “It’s the product of being really truthful to self and really having visual conversations with my peers and contemporaries and community,” Romero says. “My photographs are really an attempt to subtly combat one-story narratives.”

—

Emily Withnall lives and writes in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Her work can be read at emilywithnall.com.