Acts of Love and Protection

A half-century ago, savvy political and ideological alliances forged two federal conservation acts that transformed New Mexico

Hikers enjoy the sunrise view from the Continental Divide Trail just to the south of Cuba, New Mexico. Photograph by Sherman Hogue/ Bureau of Land Management, New Mexico.

Hikers enjoy the sunrise view from the Continental Divide Trail just to the south of Cuba, New Mexico. Photograph by Sherman Hogue/ Bureau of Land Management, New Mexico.

BY CATALINA VICENTE WITH PW CHATTEY

What’s the longest hike you’ve ever been on? A few hours, maybe a day or two? How much ground did you cover? Did you enjoy the scenery?

Now imagine a hike that’s a bit longer. Perhaps twenty to thirty miles—in one day. Now repeat—every day—for five months. Add in about 450,000 feet of elevation gained and lost, plus unpredictable bouts of dangerous weather, rattlesnakes, grizzly bears, scarce drinking water, thin air, and some of the most spectacular views on the planet. Now you’re beginning to have a sense of what it’s like to hike the Continental Divide Trail (CDT).

Stretching 3,100 miles along the spine of the Rocky Mountains and traversing five US states between Mexico to Canada, the CDT is one of the world’s most challenging hikes. As the highest, longest, and remotest of the nation’s three long-distance hiking trails, it’s the most coveted jewel in hiking’s fabled Triple Crown, a prize only 400 or so people have claimed since the early 1990s: hiking the full lengths of the Appalachian, the Pacific Crest, and the Continental Divide Trails.

Luckily, you don’t have to hike the entire CDT to appreciate what this formidable national treasure has to offer. That’s because the CDT, as part of the National Trails System, benefits from ongoing, dedicated public and private support to provide outdoor recreation, education, and opportunity for elite hikers and ordinary human beings alike.

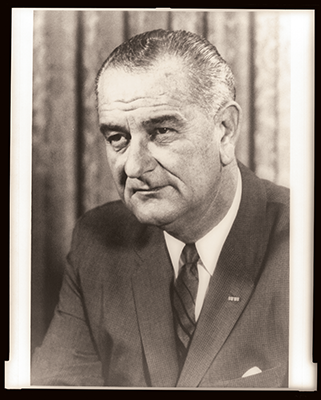

The National Trails System Act (NTSA) turns fifty this year, alongside the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (WSRA). President Lyndon B. Johnson signed both landmark conservation laws on October 2, 1968. In New Mexico, both laws have created new jobs, boosted tourism, attracted public and private financial resources, and generated important scholarly research into the state’s rich past and present physical, biological, social, and cultural landscapes.

Over the past decades, these changes helped transform mid-twentieth-century New Mexico from one of the nation’s best-kept secrets to a world-class home for its residents and a destination for visitors and people who aim to move here. One of the most notable people from the latter category was former US Secretary of the Interior Stewart L. Udall, who moved to Santa Fe from Arizona in 1989. He spent his final two decades here, working—with increasing conviction and urgency—to educate others about local and global environmental problems, activism, and justice. (His son Tom is currently the state’s senior US Senator.) [Read more in Jack Loeffler’s El Palacio article “Remembering Stewart Udall”: bit.ly/udall_loeffler]

During his service for the durations of both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, Udall positioned himself as a consistent—and persistent—champion for conservation ideas. He played a key role in the story about how the National Trails System and Wild and Scenic Rivers Acts became laws, together with a veritable cascade of related proposals, including the Wilderness Act and the Land and Water Conservation Fund (both of 1964). Over the ensuing decades, the consequences of those achievements reshaped our understanding of and relationship with the environment.

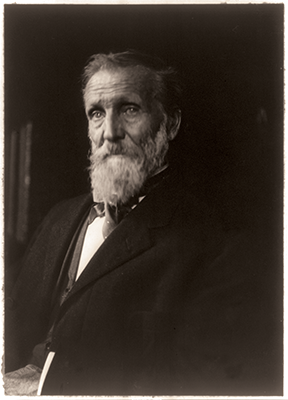

Udall’s conservation values were distilled from the principles of natural resources stewardship espoused by rugged big-game hunters and the Boone and Crockett Club, which Theodore Roosevelt founded in 1887. The traditional American conservationist believed in responsibly managing natural resources and harvesting them sustainably to ensure ongoing supplies and long-term human use.

At the other end of the spectrum, preservationists, such as Sierra Club founder John Muir, argued that natural resources need protection from human interference. Muir and other preservationists also argued that the aesthetic value alone of certain landscapes merited their preservation. For example, nineteenth-century photographs helped transform the land in Yosemite into a landscape—an object to be looked at. Distributed widely, these spectacular photographs helped pave the way for Yosemite National Park in 1890.

Broadly speaking, throughout the first half of the twentieth century, the progressive conservation philosophy won the day, not least due to Theodore Roosevelt’s newly established Bureau of Forestry and his robust expansion of federally protected lands and monuments, including the El Morro, Gila Cliff Dwellings, and Chaco Canyon monuments in New Mexico Territory. In the 1930s, Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration harnessed natural resources through infrastructure development, building enormous dams for irrigation, flood control, and hydroelectric power for booming Western cities.

After World War II, so the standard narrative goes, America’s rising middle class bought homes, appliances, and cars with powerful, gas-guzzling engines. They lived in tidy, suburban neighborhoods, and they took long weekend drives for pleasure. The US highway system provided mobility and access to remote lakes, mountains, rivers, beaches, and trails. But existing national parks and recreational sites strained under increased use.

As part of a nationwide initiative to satisfy the nation’s growing recreational appetite, Congress passed the Outdoor Recreation Act (1963), which in turn led to the establishment of the important 1965 Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF). Udall was instrumental in shepherding both into existence. The LWCF’s broad purview still provides crucial funding for major recreation sites, as well as for protected parks and wilderness areas. However, by the end of the decade, unchecked toxic industrial waste, dangerous pesticides, radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing, and simple garbage had so polluted the environment that the federal government could no longer insist that it was merely a state or local problem. The detrimental effects of these pollutants were making their way up the food chain, and mainstream Americans began to recognize the importance of ecology, the relationship between living things and their environments.

At around the same time, marine biologist Rachel Carson’s three books about ocean conservation and ecology caught Udall’s attention. Senator John F. Kennedy, whose own love for the sea helped shape his environmental consciousness, read them as well.

In what was to become her final book, the 1962 bombshell Silent Spring, Carson threw down the gauntlet against the unregulated, widespread use of the pesticides as well as radioactive fallout. Carson’s hauntingly persuasive argument became the crucial link that irrevocably tied conservation to public health. Both Udall and Kennedy anticipated the backlash, but nobody was better prepared for the it than Carson herself, who rallied hard despite suffering from terminal cancer. The chemical industry launched a vicious counter-attack on Carson’s research, her character, and her gender, but she retaliated by using her substantial Democratic Party connections to work directly with Udall and Kennedy to defend her findings. Kennedy was cautious to appear neutral and instructed his Presidential Science Advisory Committee to launch an investigation into Carson’s claims. By May 1963, the resulting report was very carefully worded:

Until the publication of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson, people were generally unaware of the toxicity of pesticides. The government should present this information to the public in a way that will make it aware of the dangers while recognizing the value of pesticides.

Congressional hearings on federal pesticide regulation began literally the next day. A week later, Udall testified before a senate subcommittee: “Carson has awakened the nation and has reminded us with compelling urgency that man is part of the balance of nature, and no matter how much we alter that balance, we still are a part of it.” By late 1963, momentum had shifted toward a more aggressive federal response to growing environmental problems. But with Kennedy’s assassination in November and Carson’s death the following April, Udall tragically lost both members of his environmental team.

Luckily, beginning in 1964, Udall found in First Lady Claudia Taylor “Lady Bird” Johnson a potent conduit to the president’s ear. They shared an unabashed love for the outdoors and the beauty of the natural world. A series of trips to federally protected sites—including a photo-op float trip on the Snake River, during which Udall pitched what became the National Trails System Act—created a personal and political bond between them. Their alliance helped keep the president focused on making measurable, visible progress toward his Great Society dream, even as Vietnam, domestic unrest, racial tensions, and the anti-war movement reached new levels of intensity.

As First Lady, Johnson actively shaped and promoted administration policies. She helped create and lobbied Congress for the Highway Beautification Act of 1965, which sought to reduce blight from billboards and junkyards on highway landscapes and replace them with native wildflowers. In this sense, Lady Bird reiterated John Muir’s advocacy for the natural landscape’s aesthetic value by including visual pollution with environmental pollution.

Udall’s ideological and political alliances with Kennedy, Johnson, Carson, and Lady Bird, together with a remarkably bipartisan Congress, helped shift environmental policy and mainstream values. The resulting legislation created a major legacy and opportunity for New Mexico and the country.

As we mark the golden anniversaries of the NTSA and WSRA, fierce debates over how to respond to today’s environmental challenges, as well as proposals to severely cut or eliminate the very agencies tasked with conservation and environmental protection programs, have led to an unprecedented ideological standoff. It’s unclear what this legislation’s legacy will look like in another fifty years, but this anniversary is perfectly timed to remind us of what we have gained, what we have to lose, and the importance of preserving America’s landscapes.

Catalina Vicente Archer is a writer and historical consultant. PW Chattey retired from the National Park Service to pursue the light as a part-time photographer and writer.

SELECTED SOURCES

Brinkley, Douglas. “Rachel Carson and JFK, an Environmental Tag Team.” Audubon (May–June 2012). bit.ly/2pVvIm0.

Johnson, Lyndon B. “Special Message to the Congress on Conservation and Restoration of Natural Beauty, February 8, 1965.” The American Presidency Project. bit.ly/2GuhpPC.

Larabee, Mark. “How the Wife of a President Helped Create the PCT.” Pacific Crest Trail Association (February 27, 2017). bit.ly/2uEZfF4.

Smith, Thomas G. “John Kennedy, Stewart Udall, and New Frontier Conservation.” Pacific Historical Review 64, no. 3 (August 1995): 329–62.

doi:10.2307/3641005.

Udall, Stewart L. The Quiet Crisis. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1963.