Traveling the Latin World through Nacha Mendez’s Music

Nacha Mendez (middle) with

the Nacha Mendez Trio, Santa Fe,

ca. 2021. Photograph by Alan

Barnett. Courtesy of artist.

Nacha Mendez (middle) with

the Nacha Mendez Trio, Santa Fe,

ca. 2021. Photograph by Alan

Barnett. Courtesy of artist.

By Leah Romero

Notes from a guitar and Spanish lyrics float out of the Hotel Santa Fe as the lobby doors open on a Friday, inviting residents and visitors to step inside and travel to Latin America. Accomplished musician Nacha Mendez’s (Chihene Nde Nation) right hand strums her Córdoba wooden guitar, laying down chords and syncopated rhythms. Her rich, full voice enters effortlessly, bringing in Spanish melodies to mix and float across the room. Mendez sits in the dining area of the hotel, lights from the floor catching the Southwestern geometric patterns on her black and terracotta skirt. A hum of conversation from diners accompanies the music, but all eyes are focused on Mendez. Her eyes are closed as she seems to become one with her guitar. One woman starts to walk by, then the music hits her ears, and she sits, entranced.

On Sundays, Mendez can be found at La Boca, the Santa Fe tapas restaurant. “I’m seeing more people come out to hear me, but one of the things that happens with non-Spanish speakers is that they’ll ask me, ‘Was that Spanish or was that Portuguese?’” she says. “I don’t sing in Portuguese, although I would love to learn the language, and I don’t sing Brazilian Portuguese to do any of the Latin jazz classics…but what happens with us when we’re having that conversation is that they’ll say at the end, ‘Well, I don’t know what you were singing about, but I really felt it’…They’re moved by it, they’re moved by the language.”

Mendez was chosen by Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham as one of seven recipients of the 2025 New Mexico Governor’s Awards for Excellence in the Arts, an honor celebrating the significant contributions of artists in the state. “The fact is that I have been working hard for many, many years—but so have so many people. There’s so many talented people in Santa Fe. And it’s either you love what you do or you don’t love what you do,” she says. “It’s just a weekly release of creativity, of joy—I feel good afterwards… It’s a great release for me to have—It’s almost like you’ve had all this pent-up emotion all week or pent-up physical thing going on with your body, whatever. Once you start singing or playing music, you’re letting it go. So I love it for that reason. It’s very healing.”

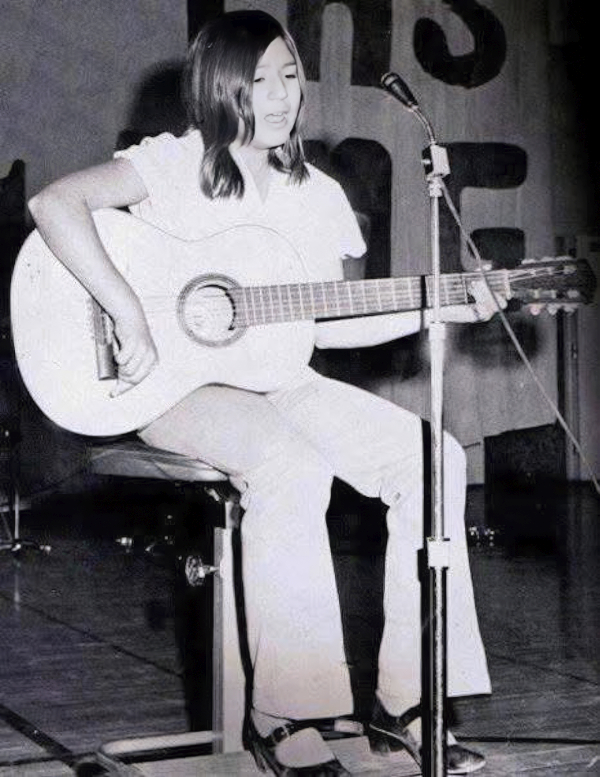

Mendez, also known as Margarita Cordero, was born in Chicago, but grew up in the Mesilla Valley. When she was six, her family moved to La Union, a colonia of southern Doña Ana County. She first picked up a guitar around that time and her grandmother was her first teacher; Mendez honors her through her stage name, Nacha.

Mendez’s grandmother traveled from California over the summers to visit and care for her grandchildren. Mendez started learning traditional Mexican songs on a plastic guitar given to her by her father, Galdino “Dino” Cordero. Huapango-style songs such as “Cucurrucucú paloma” and “La malagueña” were some of the numbers Mendez’s grandmother taught her, along with songs by José Alfredo Jiménez. “One of the songs I still do is called ‘Paloma querida’…and ‘Indita mía.’ I still do those, I learned those early on,” she says.

In first grade, Mendez had to take about a year and a half off from playing after an accident cost her the tip of her finger. “I was coming back from recess…and I closed the door behind me, but that day there was a really strong wind and it caught my middle finger on my right hand. It caught it and just severed it,” she recalls. Mendez went into shock, but a teacher quickly wrapped her hand, trying to slow the bleeding. “She says, ‘We’re rushing you to the hospital now because this is major.’ And I said, ‘No, you can’t take me yet until I find the other part of my finger.’” None of the teachers could find it, so Mendez was taken to the hospital where doctors stitched her up and placed a stent on her hand. It wasn’t until afterward that she started to feel the pain.

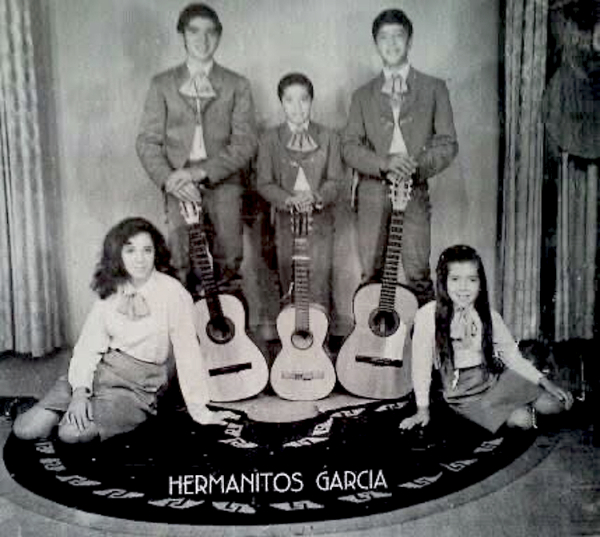

Once Mendez was finally healed, her father bought her a Tres Pinos guitar from Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, and arranged private lessons with Don Luis Garcia of Anthony, New Mexico. When she pointed out her injured finger, Garcia told her not to worry, that they would figure out a way around it. All of the Garcia family members were musicians in their own right. “They called themselves La Familia Garcia and I would take lessons from [Don Luis]. And then sometimes when he couldn’t do it, his son, one of his sons, would take over and teach me,” Mendez says. “They were actually well-known throughout the whole border region.” The family performed Mariachi at weddings and other events.

Later, Mendez played in the band at Gadsden High School. And because of an undiagnosed learning disability, music became a beacon of light for her. “I was extremely shy,” she says. “I was dyslexic, but nobody knew that I was—nobody could diagnose it. Nobody knew why I acted the way I did. And so, I personally pursued music and continued with it because it helped me. It made me feel better—it made me happy to express myself through song. It just was wonderful to have that in my life early on.”

It was Mendez’s music teacher, Ruth Madrigal, and her speech teacher, Jan Sanders, who noticed something wasn’t right. “They kind of took me under their wing and just gave me a lot of confidence,” she says. Madrigal would let Mendez hang out in the music room when she didn’t want to be in her other classes, as long as she worked on learning to read music. “I would sit there and I would try, but it was always so quiet, and she was in the other room in her office and I felt safe because I could just sit there and then just try to focus by myself.”

Sanders was bolder, Mendez says, calling her to the front of the class to talk about her week, what she was reading, or just what was on her mind. “I would start talking. ‘Well, I listened to David Bowie, the new album that he came out with, and I really liked it.’ I would just share.” Today, Mendez makes a statement with her confident personal style and performances, but gaining this confidence took a lot of time and support.

“It was continual development on my terms,” she says. “Honestly, I always felt pressure because my parents would have a barbecue or we’d be at a party and they’d say, ‘Go get the guitar and sing a song, m’ija.’ And I always like, ‘No, I don’t want to.’ And so, it was always going to be on my terms… And that’s how, through the years I was like, ‘I’m going to do music the way I want to do music.’”

Much of Mendez’s musical development happened in high school, including forming a rock band with her cousins—her uncle, Jimmy Carl Black, was a drummer in Frank Zappa’s band, The Mothers of Invention. Black’s youngest son, Geronimo Black, was a guitarist and collaborated with Mendez on her second recording. “They’re very talented individuals,” she says.

In college, Mendez studied journalism and mass communications at New Mexico State University, and her love for music led her to work in radio. She worked for KNMS, the campus radio station now known as KRUX. “It was easy for me to go to radio, because nobody could see me. I could just be behind a microphone,” she says. She enjoyed playing any music she wanted. “Because no one was there in the studio with me… I got brave. I was able to speak, and I didn’t have anybody making fun of me… I could just be myself, and I could just slowly get out of this shell that I had been in for many, many, many years.”

Mendez pauses between songs Friday night to talk to the audience. She shares that she wrote her song “Bodega de amor” in Cuban bolero style, sung in Spanish and Italian and recorded with an Italian man who happened upon her music. “He put it all together and I had sent him my voice from my studio here in Santa Fe,” she says, plucking the strings of her guitar in anticipation. She chuckles as her fingers dance and she begins singing.

Mendez followed her older brother, Frank X. Cordero, to Santa Fe in 1978 and continued her work in radio. “He had already been here, he raved about it,” she says. “He got a job for a hotel, working, and then he was just so taken by everything. And I think at one point he sent me a picture…of him and Ginger Rogers—and I was like, ‘Oh, my god, you know, that’s Ginger Rogers, so it must be a fun place.’” She went for a visit and decided then and there to make the move.

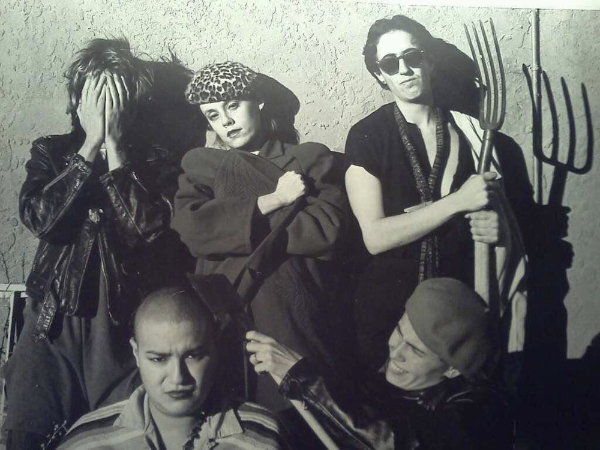

She took over her brother’s apartment lease and didn’t look back. “It was like it was meant to happen,” Mendez says. Over the years, she has worked for several other radio stations, including KAFE, KTRC, KLSK, and KIOT in Santa Fe. She also started playing guitar during the noon hour at a restaurant that is now Cafe Pasqual’s. “Back then, they were like, ‘Oh, we can’t pay you, but we can feed you and you can make tips,’ So I said, ‘I’ll take it,” Mendez says. “I did that for a little while, and then I just took off with that. I started working with other people musically, in bands.” She joined several bands, including an all-girl punk band called the Quadrasexuals, which needed a bass player. She also played in Madonna Moderna, a group that played new wave music.

Mendez relocated to the Tribeca neighborhood in New York City in the mid-1980s, after a friend invited her to visit. She continued her radio career, working at Pacifica Radio’s WBAI station. “I was [in New York] for five years, but I felt like there was a sensory overload constantly. Smells, noise—it was very stimulating—and so, I just wanted to be back in New Mexico,” Mendez says. She didn’t play a lot of music in New York, but she did study flamenco-style guitar briefly. However, her injured finger complicated some of the techniques, like playing tremolos. Her teacher, Manuel Granados, who was visiting from Barcelona, Spain, told her not to worry. They focused on rhythm guitar instead, or playing the foundation of chords and rhythms in a piece. “I took a few classes with him that were very impactful,” she says. “I’ve been a very strong rhythm guitarist for many, many, many years.”

When Mendez returned to Santa Fe, she continued performing at restaurants, performing with bands, and forming her own bands. In the early 1990s, Mendez was living in Chimayó when she was approached to join a different kind of project. “I would go … sit in church, and I would pray. I was really struggling… I would say, ‘Someday I just want to make a lot of money and do what I enjoy doing and maybe see the world.’”

A friend called one day, informing her that American composer Robert Ashley was coming to Chimayó and was searching for someone to collaborate with on an opera about lowriders. Now Eleanor’s Idea was one opera in a trilogy that explored Hispanic culture in the Southwest. Mendez helped bring the “language of the low riders” to the composition. When a singer was unable to tour with Ashley and the company, Mendez was offered a spot on the tour. “I’m memorizing three operas and then I go on tour with him and I’m seeing the world,” she says.

Mendez joined the company in New York for rehearsals and performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. The group included established American vocalists Joan La Barbara, Jacqueline Humbert, Amy X Neuburg, Thomas Buckner, and Sam Ashley, Robert’s son. The company went international, flying to Japan and visiting the major cities of Tokyo, Sapporo, Kyoto, and Kobe. They stayed in the country for a full month and went on to visit Strasbourg, France, and other locations. “It was my first time ever leaving the country,” she says. The music part of touring wasn’t difficult for her, Mendez says, but she did develop camaraderie, and there was “always a really high sense of professionalism, like being there on time, rehearsals, and learning your repertoire. All of that was really great learning for me because I had never been in a professional touring group like that, an opera company.”

After returning to New Mexico, Mendez visited her original music teacher—her grandmother. It was around this time Mendez decided to go back to her Latin and Spanish music roots and asked to use the name Nacha Mendez in her grandmother’s honor. She also returned to performing solo, just her voice and a guitar. The original Nacha Mendez passed in 2002 at the age of 97. “Her last song that she sang for my tías and I, as she lay in her bed and was in her last days, was ‘Canción mixteca.’ She sang along with my recording of that song,” Mendez says. The song was featured two years later on Mendez’s second album Volando. “That was a poignant and emotional moment but encouraging for I felt she was continuing to bless me with her voice,” she says. “¡Qué lejos estoy del suelo donde he nacido! Inmensa nostalgia invade mi pensamiento,” the Mexican folksong goes.

Mendez calls her genre Latin World; she plays traditional Mexican songs she learned in childhood but also expands into and explores music from the rest of Latin America and Spain. She writes her own pieces, influenced by tradition and her experiences. Music making becomes a collaborative experience, and Mendez gets ideas for what music to dive into next. “I’ve discovered that Latin music is very diverse…

There’s so much repertoire to choose from. And I found that when I ever perform, say, a song from Puerto Rico, or a song from Chile, or a song from Argentina, people in the audience would say, ‘I like that song. Do you know this one? Because I like what you did, because that’s our song from our country,’” Mendez says. “It creates, for me, community to get to meet people. And then I’ll say, ‘Did I do good? I mean, I didn’t screw it up, did I?’ And they go like, ‘No, no, we love your version of it.’”

Overall, she says she feels that she’s carved out a niche in Santa Fe, something different from classical music, jazz, blues, and Americana. “I think part of my success here is that I do present [Latin Music] and it’s different. Because people come from other cities where that might not be the main type of music that they hear in their hometown,” Mendez says.

While Mendez has worked hard in her career, she also dedicates her time to assisting young musicians beginning their journeys. She taught private lessons about twenty years ago, and music classes for a short time at Moving Arts Española, an after-school arts program. In March 2021, she established the Nacha Mendez Music Scholarship for New Mexican Girls of Color, which awards scholarships to girls between eight and fifteen years old who are studying music. The nonprofit organization awarded its first scholarships in May 2022 and has since awarded a total of forty-eight scholarships ranging from $500 to $2,500. The organization hosted its first annual Frida Fest Santa Fe, named after Frida Kahlo, in early November at the Museum of International Folk Art as a fundraiser for the scholarship, featuring art and a lineup of local musicians.

Mendez says she enjoys traveling across New Mexico to schools to help spread the word about the scholarship. “I want them to know that doors will open for you… Because you could be in situations and put in these places where you would never dream of being a part of, like, you could join a choral group or a band or, you know, try out for a competition or something. And you just all of a sudden, you’re like traveling and moving.” She also stays busy leading music workshops, including a recent class at New Mexico School for the Arts.

As for what is on the horizon, Mendez says she is interested in exploring the jazz genre, particularly Latin jazz, and finding new ways to bring people together through music. Mendez is a member of the Mary Esther Gonzales Senior Center in Santa Fe, where she takes the odd pottery class and uses the gym, but says she would like to find time to play music there during lunch. “I noticed some of the people don’t know the songs that I know, but I’m sure the people that are there would know those songs. Especially the Hispanic people that are there would know the songs that I’m singing. And I think they would love that.”

After a short break to hydrate and chat with restaurant staff and patrons, Mendez returns to her guitar in the dining area of the Hotel Santa Fe. One of the last songs she sings in this second set is called “The Peace Song.” The melodic line is simple, but the message is weighty: “Every day I pray for peace in the world.” She starts in English, but continues to recite the line over and over, switching to Spanish, Italian, Russian, Hebrew, and many other languages. The lyrics are like a chant that blends with the repeated notes of the guitar, and the audience quiets, focused on Mendez’s figure in the spotlight.

—

Leah Romero is a freelance journalist based in Las Cruces. Read her work here.