Pathways Through Opacity and Apocalypse

Contemporary artists navigate structures of power at the Palace of the Governors

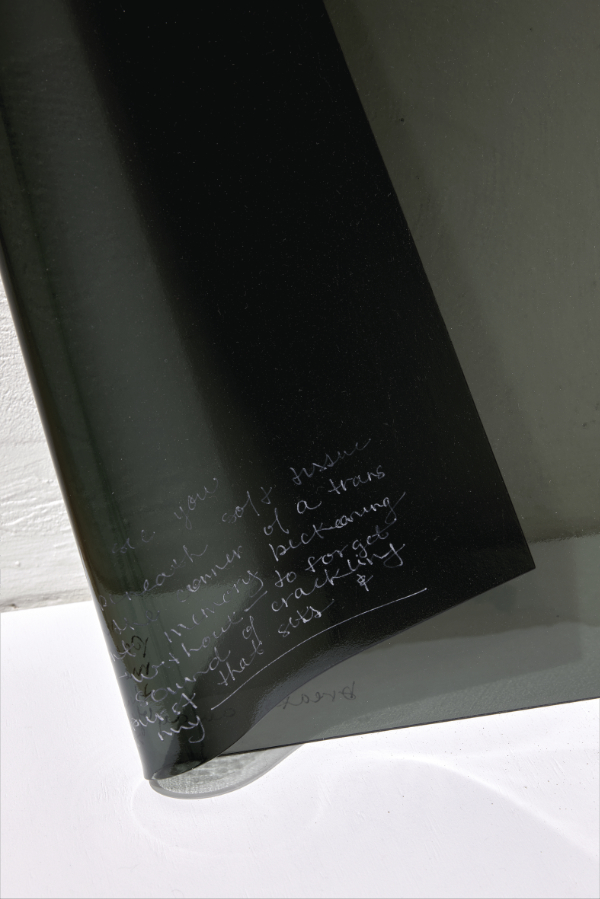

Multiple works installed by Charisse Pearlina Weston: brick to

block to base to sharpened rim, 2025 (front left); untitled corner piece

(on the balance), 2022 (back left); defiance reduced to a pinpointed warning

hum, 2025 (right). 12th SITE SANTA FE International: Once Within a Time

(details). June 27, 2025–January 12, 2026, installed at the New Mexico

History Museum, Palace of the Governors. Courtesy of SITE SANTA FE.

Multiple works installed by Charisse Pearlina Weston: brick to

block to base to sharpened rim, 2025 (front left); untitled corner piece

(on the balance), 2022 (back left); defiance reduced to a pinpointed warning

hum, 2025 (right). 12th SITE SANTA FE International: Once Within a Time

(details). June 27, 2025–January 12, 2026, installed at the New Mexico

History Museum, Palace of the Governors. Courtesy of SITE SANTA FE.

By Rica Maestas

Photographs by Brad Trone

To arrive at SITE SANTA FE’s 12th International: Once Within a Time installations at the Palace of the Governors, a visitor must first proceed through a series of doorways. Following an uncanny eyeline best suited for a dream sequence in a Hitchcock thriller, the eerie recursion within this ancient structure creates the sensation of re-entering the same room again and again. This phenomenological experience triggers an ominous feeling of timelessness, as if individual actors and actions have become gelled in the building’s material and historical heft.

It is no coincidence then, that Once Within a Time exhibitions by contemporary artists Daisy Quezada Ureña and Charisse Pearlina Weston can be found at a deliberate sidestep from this rather Jungian passageway. In diverging from the main artery of the oldest continuously occupied public building in what is now known as the United States, a viewer is freed from a centuries-old choreography, and newly able to imagine through and beyond the Palace of the Governors’ thick adobe walls. The presence of the paired exhibitions in this architectural eddy enables the artists to assert their wisdom in a setting historically hostile to women of color, and in so doing, offer urgent alternatives to hegemonic narratives about our shared past and present.

As each venue in Once Within a Time is tied to an organizing “figure of interest,” Weston and Quezada Ureña were each asked to reflect on the history of Esteban—the first African in the historical record to have set foot in the American West.

“The theme of the exhibition was so rich and there was so much information given,” says Weston of the extensive historical research that curator Cecilia Alemani shared in preparation for the show. From that background, Weston became fascinated by the layout of the Zuni-Cibola Complex, a fifteenth-century architectural site where Esteban may have met his end. “Zuni buildings included these strategic lines of sight that let inhabitants defend themselves and control who was allowed in,” she explains. “My practice deals with Black interiority, opacity, and resisting surveillance, so that kind of defensive architecture and its spaces of protection really resonated with me.”

Weston’s exhibition opens with two large glassworks that fill the small exhibition space, restricting movement, admission, and lines of sight in homage to Zuni Pueblo architecture. To the left, a collection of smoky glass slabs entitled brick to block to base to sharpened rim renders its physical boundaries ambiguous through repetition and layering. This uneasy visual prompts viewers to move with caution and a heightened awareness of their bodies, for fear of disrupting a delicate, sharp-looking, amorphous piece.

“I wanted to make people have to navigate really intentionally around these works,” Weston says. “I wanted that feeling of precarity relative to the glass to reflect the precarity of Black lives in these spaces.”

The surveillance and concealment of Black bodies within Western architecture is a frequent touchstone in Weston’s practice, a theme further explored by the wall-hanging collage called defiance reduced to a pinpointed warning hum. Situated to the right of the exhibition entrance and across from brick to block to base to sharpened rim, this piece layers broken glass, printed canvas, epoxy, and other materials within a large wooden frame evocative of a window. Though this murky piece refuses easy parsing, its form nods to Weston’s ongoing meditations on broken windows policing—an ill-defined and widely critiqued policing ideology that correlates an increased focus on petit crimes (like breaking a window) with an eventual drop in violent crime. Though variations of this strategy have seen widespread implementation in the United States—New Mexico included—since its popularization in the 1990s, broken windows policing has been continuously shown to supercharge police surveillance, incarceration, and abuse in communities of color. Questioning equivalencies between transparency, perceived order, and safety, Weston’s window-like work reminds us that surveillance and policing are ultimately modes of oppression, not protection.

According to the artist, protection can be found in relationship rather than transparency, as evidenced in this exhibition by the dynamic created by the two larger pieces, and the smaller work they partially conceal: untitled corner piece (on the balance). Nestled between a corner and a built-in fireplace, this slight, curving glasswork, adorned with lines of handwritten text, is rendered quasi-illegible by the curve of its surface and its position relative to its protectors. This arrangement bucks perceptions of glass as a placid, transparent medium through which one can remotely extract information (think windows, camera lenses, phone screens, etc.). Instead, Weston’s installation complicates our understanding of her chosen material, transforming glass from something so ubiquitous as to be rendered functionally invisible into a medium fully capable of concealing, distorting, and impeding—and importantly, one that reflects social roles and relationships.

Taken as a whole, Weston’s exhibition asserts that glass is not neutral or natural in our built environment, but in fact carries far-reaching ideological, practical, and social implications. Situating her work alongside Édouard Glissant’s essay “For Opacity” during our interview, Weston echoed the idea that the Western demand for perpetual transparency is a colonial strategy that advances white supremacy. In other words, if participation in society requires our constant comprehensibility, we must not only efface our individual complexity to remain consumable to others but also submit to the omnipresent surveillance and policing that maintains our flattening en masse. In symbolic dissent, the persistent ambiguity and personified positioning of Weston’s works challenge viewers’ assumptions about glass as a medium within the gallery and beyond. And more broadly, the work asks us to consider opacity and the discomfort of not knowing as a viable alternative to the oppression inherent in compulsory transparency. To borrow from Weston’s musings during our interview, “What happens when we sit with our not-knowing-ness? How might it be generative?”

The ambivalent role of transparency within historical constructions is significant in Quezada Ureña’s exhibition Past [between] Present as well, evident in the content of the works on view, and in their placement within the Palace of the Governors. One full wall of the gallery is punctuated by gleaming windows looking out onto the bustling plaza. On opposing walls, cutouts behind plexiglass reveal the New Mexico History Museum’s earthen structure beneath its white-cube veneer. The simultaneous visibility of the original architecture, the smooth, contemporary renovation, and the adjacent plaza lends the exhibition a sense of permeability, where portals between the past and present, inside and out, remain painfully open.

Past [between] Present engages directly with this architectural liminality by not only replicating the museological use of plexiglass in the installation, but by also displaying the artist’s curated artworks and artifacts between shoring posts. More often seen in construction or archaeological sites, the shoring posts in Quezada Ureña’s installation elevate some objects over others, demonstrate the historical, social, and political forces they withstand, and minimize deleterious effects on the historic site. Where art installation often requires invasive, damaging interventions to the spaces they occupy (like drilling into a wall or ceiling), Quezada Ureña’s works hover using pressure alone, like bones healing beneath a plaster cast.

As a viewer navigates this array of shoring posts and floating vitrines, it becomes clear that this vertical force barely begins to contain the power of the items borne between. Ghostly porcelain garments float alongside highly charged historical artifacts, including (but not limited to) guns belonging to New Mexican Confederate soldiers and glittering soil from the controversial excavation of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. However, the quietest of these historic pieces may also be the most explosive: shards of a bell likely used during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Like shrapnel lodged beneath the skin, these bell fragments rest directly on the centuries-old adobe bricks behind the museum’s plexiglass barrier, rather than within one of the artist’s vitrines. While this striking commentary might be easily overlooked by visitors unaware of local history, or those who simply miss the ceramic splinters in the Palace of the Governors’ side, this subtle choice speaks to lingering social rifts that have strained Santa Fe for centuries.

As the only successful Native uprising against a colonizing power in North America, the Pueblo Revolt expelled Spanish settlers from New Mexico and beyond, following decades of extortion, enslavement, and abuse of Indigenous peoples. Puebloan communities then occupied the Palace of the Governors for several decades, during which some say the tradition of vending under the portal began. This practice remains visible through the windows of the exhibition, though so too does the Soldiers’ Monument’s stone panel belying “savage Indians” and the annual celebration of Spanish forces retaking the Palace. This tension between colonizer and colonized has been on display on the plaza for centuries, but Quezada Ureña’s choice to slip historic Picuris bell fragments under the Palace’s plexiglass protection quietly honors the centuries of Indigenous resistance to social, economic, and environmental oppression in New Mexico.

Opposite this powerful installation, Past [between] Present highlights one of the most pressing instances of ongoing colonial injustice impacting the Land of Enchantment: nuclear extraction on Native lands. One of the artist’s porcelain sculptures takes the petrified form of a garment selected by a curandera to protect local journalist Alicia Inez Guzmán during her investigative tour of Los Alamos National Laboratories. Adjacent to this haunting piece is a retablo depicting Our Lady of Light and a ceramic child’s blouse filled with blue corn seed. Viewed optimistically, these companion pieces might suggest divine guidance leading the next generation toward nonviolence and ethical land use. However, the process of creating the artist’s sculptural works might suggest a more ominous read. After being soaked in slip, the sometimes-found, sometimes-gifted reference garments are incinerated in the kiln, leaving disembodied traces of their obliterated forms not unlike the eerie “shadows” left by Hiroshima and Nagasaki residents vaporized in atomic warfare.

A similarly apocalyptic interpretation lurks within the retablo depicting Our Lady of Light. While her visage could be viewed as a savior to Catholic viewers, she might also refer to the eponymous Spanish colonial missions that sprawled over present-day Texas. More broadly, the invocation of Catholic iconography might point to the role of the Church in the colonial occupation of the Americas and genocide of Indigenous peoples: an era historian Gerald Horne has posited as an apocalypse. This interpretation may be bolstered by the resemblance between folk depictions of Our Lady of Light and Our Lady of the Apocalypse (a precursor to La Virgen de Guadalupe), both of whom hold a male infant before a celestial backdrop of attending angels. Analyzed thus, the Light in question might just as easily refer to the possibility of nuclear annihilation as it does to a guiding light.

As we grapple with the weighty sense that Quezada Ureña’s objects impart about our presence amid contemporary apocalypse, the artist also provides some needed inspiration through the remaining artifacts in the exhibition. There are cases bearing historic Zuni pottery, beaded moccasins, and early belts made by renowned Santa Clara artist Porter Swentzell, a scale balancing the hands of an elder with those of a child, and a neatly folded ceramic t-shirt beneath the Quezada family molcajete. There is a map showing Cíbola, the site of Esteban’s ultimate liberation from slavery, be it by concealment or by death. Through these tender pieces, we might see our own freedom as made possible through focus on craft, creativity, community, and cultural transmission of knowledge.

Though each visitor to the Once Within a Time exhibitions at the Palace of the Governors will draw their own conclusions about the significance of the works on view, the aching social traumas they illuminate are undeniable. Both artists’ installations point to moments of confusion, flux, and unspeakable violence—from colonialism and nuclear extractivism to racist surveillance and policing—and demand that we acknowledge our presence in this ongoing history. In Quezada Ureña’s words, “Things are shifting, and we need to understand what we’re becoming.” A hopeful answer to this urgent uncertainty may lie at the intersection of these exhibitions: While implicating architecture in the persistent problems that plague us, Weston’s and Quezada Ureña’s work collaborates with the exposed adobe of their setting to illustrate the astonishing forms tiny flecks of sediment can take together. Weston’s mysterious glassworks, Quezada Ureña’s delicate ceramics, and the very walls of the Palace of the Governors, are all examples of the persistent social power of the things we build together, and the enduring generativity of many.

—

Rica Maestas is a socially engaged artist and writer from Albuquerque, whose creative and cultural work elevates lived wisdom and prioritizes mutuality.