Connecting Time, Place, and People

Employed on sovereign lands, the “Acoma Method” is a model for all archaeologists

New Mexico State Tourist Bureau. Corrals at the Foot of Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico, 1957.

Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), Neg. No. 090837. New Mexico Magazine Collection.

New Mexico State Tourist Bureau. Corrals at the Foot of Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico, 1957.

Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), Neg. No. 090837. New Mexico Magazine Collection.

By Laura Paskus

On a warm August morning about 150 years ago, the people who lived on the sandstone promontory above Di’ Chuuna would have looked east at the slumbering lines of Kaweshtima.

Even with the summer harvest underway, they might have wondered when snow would start draping the mountain. Today, the people of Acoma still time spring plantings to the shifting of that white shawl, so that when snowmelt arrives in Di’ Chuuna and the ancient irrigation canals, they are ready.

In the 1870s and ’80s, the riverbank would have been open, not yet choked with salt cedar planted by agents of the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. And the stream would have run higher and more consistently, before a warming climate and upstream water demands started to drop and dry its flows.

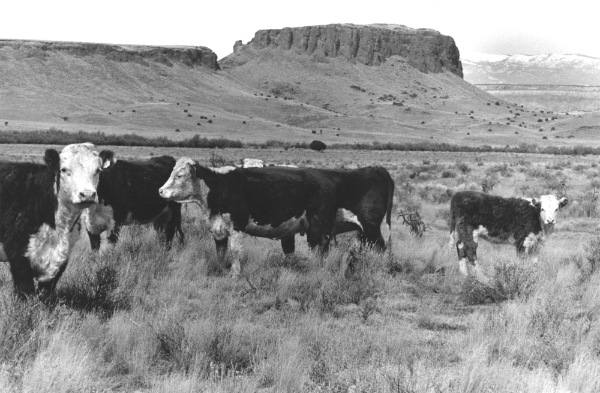

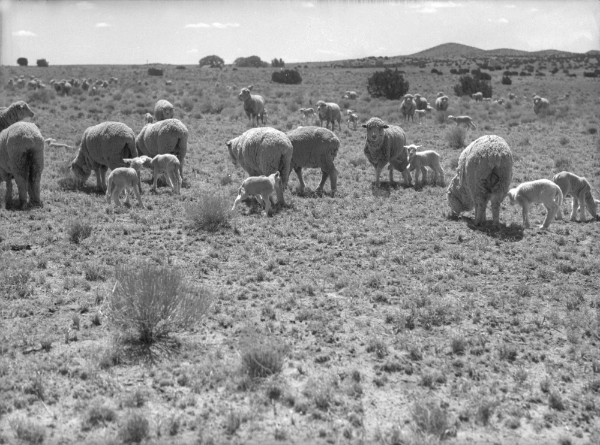

From this vantage point, the family living here would have watched their sheep and goats in the valley below, and over time, seen railway cars travel on newly laid tracks, and early automobiles putter and zip past on Route 66.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, significant changes were underway at the Pueblo of Acoma, whose people migrated from the north, passed through Wáphra’ba’shúka (Chaco Canyon) and Kásh’kútruti (Mesa Verde National Park), and settled at Haak’u more than ten centuries ago. At Haak’u, or Old Acoma, people harvested and conserved rainwater for centuries and even rebuilt the multi-story village after the Spanish destroyed it and killed and tortured hundreds of Acoma men, women, and children in the late sixteenth century.

Infinitely adaptable, the people of Acoma spent centuries developing knowledge of how to survive and flourish in the arid Southwest. And even as they maintain their culture, traditions, and ceremonies, they are a part of all that shifts and changes, too.

“When the railway came through here, there were (Acoma) people working on the construction, and they farmed at the same time,” says Steven Concho, the Pueblo of Acoma’s tribal historic preservation officer, as he describes the home that once stood above the river valley.

During that era, some people moved away from Haak’u, bolstering villages like Acomita and McCartys. People farmed and raised livestock along Di’ Chuuna. And as families grew, they added more living spaces, storage rooms, and corrals.

“From here, you can see all around the whole valley, up and down, and it was an important area to live at that time,” Concho says. The people would have witnessed and been a part of significant changes at the Pueblo of Acoma and across the West.

“This was a transition (time) between all the hustle and bustle of the West and the Acoma people still practicing their traditional culture,” says Concho. “It was around that time, the 1880s and 1900s, where you start to see this shift of people coming into the valley and starting to stay here a lot longer because all the resources are here.”

The mountain runoff, springs, and stream provided water, and people planted crops throughout the valley. “This was before Wal-Mart and convenience stores, so they had to rely on the land, raise sheep, raise cattle,” he says. “Coming to this valley made it a little bit easier for them.”

The railway brought jobs, and Route 66 made Albuquerque and the burgeoning uranium mines near Grants more accessible. Eventually, these pueblo communities closer to the highway and railway also gained access to electricity.

“Rather than being clustered very closely in a nucleated village, there’s a transition to modernity during this period, and even a rearrangement of how they were organizing their space domestically,” says Dr. John Taylor-Montoya, executive director of the New Mexico Office of Archaeological Studies.

Atop Haak’u, buildings grew by stories in the mesa’s limited space. In the communities along Di’ Chuuna, homes could spread horizontally, and today, archaeologists study not only what was held within the rooms—ranging from traditional pottery to canned foods—but how they were laid out. In partnership with community members, these archaeologists also better understand a family’s connection to landscape, culture, and history.

People lived in the home on the promontory above Di’ Chuuna, or the Rio San José, from the 1870s through the 1930s or 1940s, according to Taylor-Montoya. They raised sheep and goats, and used a mix of traditional Acoma pottery, grinding stones, and selenite (also used for the windows), along with commercially available metal tools and containers, porcelain tableware, and glass bottles.

Over time, the home’s sandstone walls collapsed. And the cleared outdoor areas—one a plaza or courtyard, and the other a corral or threshing area—had become ticked with weeds. The site was only excavated and studied ahead of an infrastructure project, the Mesa Hill Bridge and Road Extension, that the Pueblo of Acoma has needed for almost fifty years.

For decades, the Pueblo has sought funding to build a new bridge over the railroad tracks that separate its villages from Interstate 40. Since the 1970s and ’80s, as train traffic increased on the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway, residents and visitors have endured longer and longer waits on the road. Ambulances and other emergency vehicles get stuck at the railway crossing too, sometimes for up to twenty minutes if multiple trains are crossing.

In 2012, an average of ninety-five trains a day passed through the Pueblo, says Raymond Concho, director of community development at the Pueblo, and Steven’s uncle. Today, the official numbers are down to about sixty, but the trains are longer—sometimes up to three miles in length—and are often double-stacked.

Now, with federal funding in place, Mesa Hill Bridge and Road Extension is finally moving forward. The project will include a new span of road and a thousand-foot bridge over the railway, the river, farmland, and a natural gas pipeline. While advocating for and planning for the bridge, the tribal administration held community meetings and listened to traditional leaders, says Raymond Concho.

The Pueblo doesn’t undertake new development lightly, especially if it will destroy a homesite. But the project, which will level the sandstone rise and destroy the former homesite, is necessary for the community’s safety.

“If I had lived here, I would watch my sheep down in the valley,” Raymond Concho says while walking across the site, pointing to original plaster or whitewash still visible at the base of sandstone rocks that once formed a room. A train appears, and he counts the minutes it takes to pass.

Department of Cultural Affairs.

Ahead of the bridge and road construction project, the Pueblo hired the New Mexico Office of Archaeological Studies (OAS), and in late 2024 and early 2025, crews excavated the homesite. During this project, OAS built on work models and relationships developed a decade ago, which incorporate traditional and community knowledge, science, and public education.

“The ‘Acoma method’ is more than just collaborative or community archaeology, in that you’re working with and among members of the community,” says Taylor-Montoya. “The crux of it is having a real partnership.”

In 2014, OAS worked on an archaeological survey ahead of an energy project crossing the Pueblo’s lands. The Pueblo of Acoma Historic Preservation Office designed the project and archaeologists worked closely with the community. Cultural monitors accompanied archaeologists, who would oftentimes follow behind, as they walked the ground in staggered transects, looking for signs of buildings, artifacts, shrines, and other notable or special places on the landscape. Using a tiered system, they identified sites within the project area and preserved the privacy of the Pueblo’s cultural sites.

At the top of the tiered system were the most sacred and culturally sensitive areas, explains Taylor-Montoya. Acoma elders or monitors identified these places, which outsiders like archaeologists are not allowed to visit, never mind record. Then there were culturally sensitive places archaeologists were allowed to see, but which were mapped with a buffer around them for privacy. Finally, there were what archaeologists would traditionally call sites. Those could include remains of buildings or certain activities but weren’t necessarily culturally sensitive.

When it came time to work on the Mesa Hill Bridge site, OAS adapted its usual excavation practices, as well. Going into their very first meeting with the Pueblo, Taylor-Montoya says the archaeologists wanted to respect the boundaries, conditions, and specifications Acoma set. The state also integrated community members into the project as cultural monitors and hired local people to work with the state crew on the excavation.

While the project was ongoing, elders and others would stop by the site to check in, ask questions, and share their knowledge. Teachers from Haak’u Community Academy and Haak’u Learning Center brought students to visit as well. “They were able to see what they were doing over there and get it in their heads to become future archaeologists, future tribal historic preservation officers, whatever,” says Kathy Felipe, program coordinator for the Tribal Historic Preservation Office. “They were able to look at the site, and they have millions of questions.”

Traditionally, archaeologists were little more than looters and pot hunters. In the nineteenth century, the Southwest was full of white men who ripped apart sacred sites and ancient buildings, and desecrated graves. Even in modern times, archaeologists and researchers have often treated human remains and funerary objects with curiosity rather than respect. People who had been carefully laid to rest in the earth to be with their ancestors were torn from the soil, measured and photographed, and placed in boxes upon shelves in hundreds of museums and storage facilities.

There have been movements within the profession to work more closely with Native communities—and there are more Native archaeologists, as well—but archaeology remains an extractive field of study. And while the Pueblo of Acoma can’t control what archaeologists and researchers do on lands beyond their federally designated reservation, within their own boundaries they choose to work with archaeologists who show greater respect for the past, the landscapes, and the living community.

“Working with archaeologists, I like making sure that they understand our story and where we’re coming from,” says Steven Concho. He also wants to ensure they understand the people of Acoma. Typically, Southwestern archaeologists were drawn to—and valued—masonry buildings, kivas, and other human-made sites, such as where someone knapped a weapon or tool, cached a water pot, or ground and processed plants.

“What is important to us is not just a building,” says Steven Concho. “But it’s everything that ties to it, the landscape, the trees, the water, the fields or plants, its relationship to the mountain,” he says. “Everything is connected to a site.”

Steven Concho recalls the words of Aaron Sims, from the Pueblo of Acoma, who said, “One of the biggest issues that we constantly run into is the understanding of what is a cultural resource. For Acoma, all ancestral pueblo archaeological resources are cultural resources, but not all cultural resources are archaeological in nature.”

All archaeologists should strive to understand and respect tribes, whether they are working on or off sovereign tribal lands. Doing work this way is sensible, says Taylor-Montoya, and it bridges the gaps between scientific and traditional knowledge. It’s also replicable across communities and archaeological companies.

“Why shouldn’t we be doing this? Why can’t we have all this work in concert to bring a full, rich story? Sometimes it’s not intuitive. Sometimes (the scientific data) tells a different story than what the shared memory is,” Taylor-Montoya says. “But we should respect and value what has been handed down through the generations from the people who witnessed those things.”

Archaeological work like this fosters understanding and empathy, he says, and brings knowledge together equitably. “One of the cool things about archaeology is that it’s not just (studying) big people and great events,” says Taylor-Montoya. “It’s everyday life. So, you’re talking about what you made for a meal or how you cooked bread, and when you harvested corn. Those are shared human experiences.”

At the now-excavated homesite above Di’ Chuuna, Raymond Concho points across the valley to where he grew up, and to where Steven’s house is today. The past, present, and future are all here, watched over by the mountain, by Kaweshtima. Raymond recalls his childhood. He talks of an upcoming weekend celebration. And he sees the bridge where it will someday cross above the railroad tracks. All these stories, times, and places are connected.

Meanwhile, no matter where they work, archaeologists can be better community members. “The most important thing moving forward is archaeologists and tribes working together,” says Steven Concho. “No matter what the project is, we have to work together. We don’t own the land, we are stewards of the land. And our job is to protect it.”

—

Laura Paskus is a longtime writer and producer based in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and author of At the Precipice: New Mexico’s Changing Climate.