Art and Activism at Highlands University

Photographs from the Voces del Pueblo Exhibition

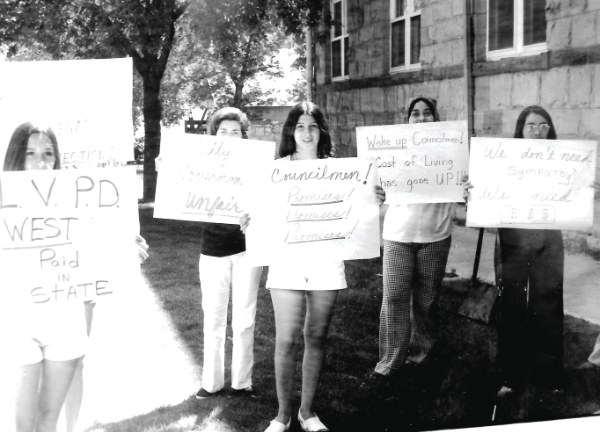

Las Vegas Police Department Protest, 1973. Silver gelatin print, 5 ½” x 9”. Private collection of David Montoya and Susan Seymour.

Las Vegas Police Department Protest, 1973. Silver gelatin print, 5 ½” x 9”. Private collection of David Montoya and Susan Seymour.

By Myrriah Gómez

If you are walking on the New Mexico Highlands University campus in Las Vegas, New Mexico, and you find yourself on the south side of Hippie Hill, and you know where to look, you can see the phrase “Viva la Raza” scratched into the sidewalk. You can see it best during golden hour, when the sun starts to set across the plains of Nuestra Señora de los Dolores de Las Vegas Grandes. And, if you stand outside of Professor Eric Romero’s office, you can see a poster for the first meeting of the National Caucus of Chicano Social Scientists in 1973, the organization that would later become the National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies (NACCS).

As a twenty-year-old Chicanita, I sought out that history when I was a student at Highlands. I sought it out in classes like Chicano Literature with Professor Daniél Martínez and Poesía Chicana with Professor Lillian Gorman. When Highlands saw a mini resurgence of the Chicano activism of the 1970s during the early 2000s, the old timers told us about the murals activists had painted on campus during the Chicano Movement. But that story had been covered up as part of the larger whitewashing—both literal and figurative—of student activism at Highlands.

A new exhibition documents Chicano art and activism at NMHU in the 1970s. Voces del Pueblo: Artists of the Levantamiento Chicano in New Mexico, currently on view at the National Hispanic Cultural Center until February 8, 2026, documents the art and activism of six featured artists— Ignacio “Nacho” Jaramillo, Juanita J. Lavadie, Francisco Lefebre, Noel Márquez, Roberta Márquez, and Adelita M. Medina—all of whom were students at NMHU in the 1970s. The exhibition was curated over seven years by Dr. Ray Hernández-Durán and Dr. Irene Vásquez and contains 146 artworks by the six artists. Themes include community, family, querencia, land, home, and others. A focus of the exhibition is El Movimiento (the Chicano Movement).

In stark contrast to the colorful drawings, paintings, and tapestries created by her peers, Adelita M. Medina’s black and white photographs help narrate the underlying story that the artists tell about the Chicano Movement at Highlands. Her photography documents a multigenerational movement that occurred not only at the university but across the city. The roles that women and children played during the Movement have been overshadowed by the stories of the men, and Medina’s photos provide a window into the educational front of the Chicano Movement in New Mexico. Most interestingly, her work provides a snapshot of the little-known alternative school for Chicano youth in Montezuma, just five miles north of Las Vegas. At the center of El Movimiento in Las Vegas was the demand for educational equity at the K-12 and college levels and a culturally relevant curriculum to help students connect to their language, history, and cultural practices.

The Highlands Uprising

In 1970, upon the impending retirement of NMHU president John C. Donnelly, students and community members lobbied the Board of Regents to hire Dr. John A. Aragon, a Nuevomexicano educator from the University of New Mexico. Instead, the Board selected Charles Graham, who had been dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater.

After Graham accepted the initial offer, Chicanos began protesting. Students occupied the administration building at Highlands for eight days in May 1970. District attorney and president of the West Las Vegas school board, Donald A. Martínez, filed a lawsuit to stop the hiring of Graham. Ultimately, Graham did not take the position and later stated in an oral history interview that he declined because it was the “peak of the Chicano Militant Movement,” and that Chicano students at Highlands “never had a chance to do much there, except go and learn how to be teachers in a very traditional Anglo way.” Graham acknowledges that “the Board was wrong to appoint me, and I think they were almost deliberately ignoring some of the factors in this situation.”

The regents allowed the vice president under Donnelly to act as president until Dr. Frank Ángel was hired in 1971. Ángel was Las Vegas-born and the first Chicano to be hired as president at Highlands. In his speech at Ángel’s inauguration, U.S. Commissioner of Education S.P. Marland Jr. noted: “Thus it seems to me, in a sense that I am sure President Ángel will understand, somehow inaccurate to celebrate the fact that, 340 years later, one of our 1,400 senior educational institutions should be headed by an American of Mexican descent. Instead of saying, ‘Isn’t it wonderful?’, we should be asking, ‘What took us so long?’”

Ángel was the first Chicano president of any four-year university in the U.S. The New York Times wrote of his hiring: “He is widely regarded as a father figure, or patton [patron], for Chicanos who have risen through the state’s colleges and universities.” During this time, fifty-four percent of students enrolled at Highlands were Chicano. Las Vegas was—and remains—a low-income, predominantly Hispanic-identifying community. Although Ángel was not the protestors’ first choice to become NMHU’s president, Martínez said at the time, “If you’ve been knocking at a door for many, many years and you get it opened a crack, you’re not going to be mad at the fresh air coming in.”

The protests led to the creation of cultural studies programming at Highlands and eventually resulted in the hiring of several Chicano professors and administrators. Although there were similar efforts on campus to add a Black Studies curriculum, the university made it impossible to institute an intercultural program that included both Chicano and Black Studies; thus modest efforts to create a Chicano Studies program prevailed. Willie Sánchez, an associate professor of math at NMHU during this time, told The New York Times in 1971 that, “The Chicano element for some time has felt it is necessary to provide proper role models. […] It’s pretty difficult to convince a kid that there is a place for him in the world when there is nobody to look up to.” He went on to say: “If all [NMHU administrators] are going to do is be a pallid reflection of Northwestern University or of the University of New Mexico, then let’s buy a bus ticket for the students and send them there.”

The Chicano Movement brought to the surface many of the lingering tensions from New Mexico’s territorial period. This included the creation of a hyper-mythologized Spanish American identity for Nuevomexicanos, who had adopted a Spanish identity in large part due to the push for statehood, when being “mixed” blood was looked down upon and seen as a barrier to advancement. Across the country, the Chicano Movement was a resuscitation of an Indigenous past that many Nuevomexicanos still found unacceptable. However, almost everyone agreed that the Spanish language should be protected and that a just education included the ability to use, learn, and teach Spanish in the classroom. Many of the students participating in the protests at Highlands had been punished as children for speaking Spanish in the classroom, and now they protested for the inclusion of Spanish in the school curricula as a fundamental right.

Chicano Studies and Art

One professor hired to teach art and Chicano Studies at Highlands made a lasting impact. Pedro Rodríguez was hired in 1971 to direct a new Chicano Studies program. All six artists exhibiting work in Voces del Pueblo at NHCC were Rodríguez’s students at Highlands. In 1972, some of them traveled to Mexico City with Rodríguez and learned to paint murals. When the students returned, they painted various murals across campus depicting Chicano history and culture under his tutelage. The murals appeared in Connor Hall, Burris Hall, and the student union building, among other locations. However, according to Hernández-Durán, President Frank Ángel is remembered as having publicly stated that not only were murals not art, but that Mexico had nothing to do with New Mexico. He ordered them to be whitewashed.

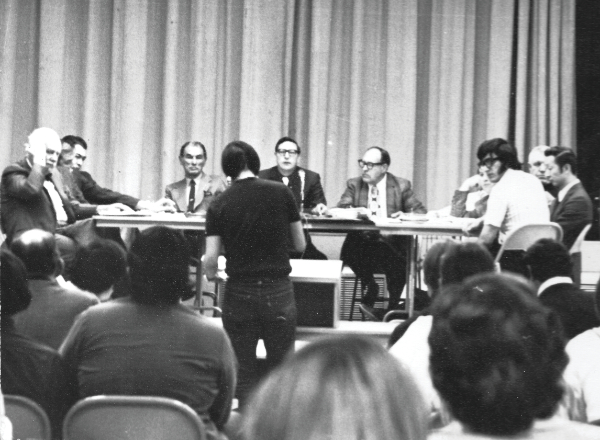

NMHU student Adelita M. Medina’s photo “Meeting with Frank Ángel and the Board at NMHU” (1973) documents one meeting in which Chicano students protested Ángel’s presidency. Chicano activists were targeted by the administration during this time, especially the artists. Francisco Lefebre was expelled by Ángel for painting a mural of Ché Guevara at the student union building. Rodríguez was later denied tenure and dismissed from Highlands, and Juan José Peña was hired to replace him. Ultimately, the Chicano Studies program at Highlands did not endure. In Medina’s “What Happened to Chicano Studies?” (ca. 1973), a group of Highlands students stand in front of the administration building protesting with signs; a banner with the United Farm Workers eagle hangs from the balcony behind them.

The protests at Highlands inspired Chicano students in the East Las Vegas City Schools to protest what they deemed discriminatory practices and the absence of a culturally-relevant curriculum. Several of Medina’s photos show protests at school board meetings and outside of the Las Vegas Police Department. One photograph shows five Chicanas standing outside the police department holding protest signs in support of several activists who had been jailed. Highlands students were the central figures in the protests across town.

Medina was a student in 1971 when she became involved in the movimiento. She was a single mother to a six-month-old baby and living in an apartment next to the Plaza Hotel when she heard protesting outside in the park. She saw students from Highlands chanting and marching and saw her older brother Benjie and his friend Fred. “We’re protesting against the discrimination against Chicanos at Highlands,” her brother said. “I think I’m gonna march with you guys,” she told them. “And that changed my life forever,” Medina says.

She avoided the stereotypical roles that women were often assigned, even in activist spaces. “They’re gonna ask us if we know how to type,” she told her friend Sylvia Gutiérrez. “Tell them we don’t know how to type.” Sure enough, when asked the expected question, the women said no. Medina and Gutiérrez disrupted the male space of the Movement in Las Vegas in multiple ways. They often met the other leaders at the home of Lucy López (Mama Lucy) on Hot Springs Boulevard to strategize about what actions to take at the university. According to Medina, the local politicians invited them to these meetings.

During the summer of 1971, Medina began working on the famous Chicana newspaper El Grito del Norte with Elizabeth “Betita” Martínez in her hometown of Española. She was hired as a proofreader and soon learned newspaper layout and photography. Her photography training helped her capture the images now on view in the Voces del Pueblo exhibition. When El Grito moved to Las Vegas, Medina continued working on the paper until its final issue in July/August 1973.

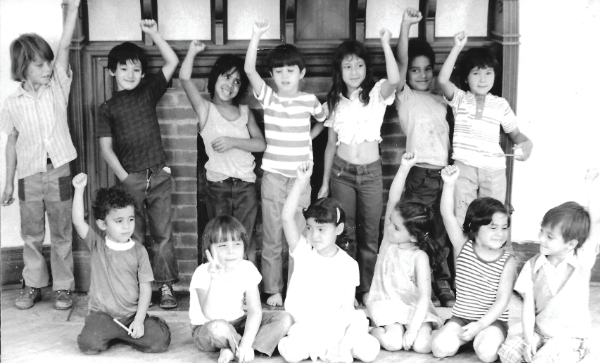

Her photographs in the exhibition document the events at Highlands, the walkouts and marches by East Las Vegas middle and high school students, and the grassroots education that happened just outside of Las Vegas at the Escuela Antonio José Martínez in the 1970s. As Hernández-Durán writes in the exhibition text, “Photographs documenting the Chicano movement in New Mexico show children learning about farming, conveying how this longstanding love and respect for the land has been passed down from generation to generation.”

Medina’s photos are powerful for various reasons. Most images of the Chicano Movement across New Mexico universities depict violence. The New Mexico Museum of Art curriculum on “The 1970 Protests & Violence at the University of New Mexico” is entirely composed of images ranging from photos of the armed National Guard to paramedics loading a sheet-covered body onto a stretcher. Medina’s photos instead document women and children planting seeds, making food, and holding up signs during peaceful protests.

Escuela Antonio José Martínez

On August 26, 1973, Chicanos Unidos para Justicia (CUPJ) took over one of the buildings at the Montezuma Castle, which had recently been a seminary for Mexican Jesuits until the Archdiocese of Santa Fe announced plans to sell the property in 1972. That day about one hundred people marched from the Plaza Vieja in Las Vegas—after celebrating an outdoor Mass there—to the Montezuma Castle. CUPJ had been petitioning the Archdiocese of Santa Fe and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops to rent the castle to start a school for Chicano youth, to no avail.

After CUPJ occupied the building and refused to leave, the archdiocese began to work with them. In a letter to the general secretary of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, Archbishop James Peter Davis states, “After many meetings with those concerned, I am pleased to report that the Montezuma Seminary property problem has been thoroughly researched and the following conclusions are in order: […] The old buildings, including the castle, the former chapel building and sufficient farm acreage to provide agricultural development for educational purposes and food supplies for the school, will be made available by grant of use to Chicanos Unidos para la Justicia.” In this way, the Escuela Antonio José Martínez, named after Padre Martínez of Northern New Mexico fame, was established.

The CUPJ assigned Adelita M. Medina and David Montoya as coordinators for the Escuela. While it was not accredited by the New Mexico State Department of Education, it did earn accreditation from the Rio Grande Educational Association (RGEA), a regional accrediting agency for non-public schools. In January 1974, the New Mexico Supreme Court ruled that the State of New Mexico could not regulate non-public schools, which validated the RGEA accreditation. The school had approximately seventy-five students with instructors that included licensed teachers and professors from NMHU. According to co-curator Irene Vásquez, “Students from NMHU and community members organized the Escuela Padre Antonio José Martínez to provide youth with a culturally inclusive education that centered the wisdom and resilience of their land-based communities.”

In one of Medina’s photographs, “Niños sembrando en Moctezuma [sic]” (1973), a dozen or so children line a bordoin an empty field and sow seeds while one shirtless boy around five years old looks on. In “Chicanitos at the Escuela Antonio José Martínez” (1973), a group of school kids pose in front of a fireplace for a class photo, but in this one, the kids all raise their arms in a power fist, and one child opts for a peace sign. All the kids have smiles on their faces.

In April 1973, CUPJ held a Chicana Conference at the Escuela. People came from across New Mexico and Texas, Wisconsin, Delaware, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania to address issues related to housing, healthcare, welfare, education, employment, childcare, sex discrimination, and the penal system. Those were the issues in which the Escuela Antonio José Martínez

was interested.

In “Sylvia and Pita in the Kitchen at the Castle,” three rows of lunch trays line an industrial kitchen counter. Two women stand in the foreground with two men in the background. Medina says the women of Las Vegas—mothers of the children who attended the Escuela—showed up to run a baking cooperative and bake bread at the castle to share with the families.

The Escuela was, perhaps, one of the best examples of mutualismoin Las Vegas during that era. One mother, Esmeralda Torres, wrote in a letter published in an issue of Tierra y Libertad: “The bread Co-op has been a very good community program also. It has given us ladies a cooperative community spirit that had almost been lost in our culture, plus the practical knowledge and savings. Again, I want to say mil gracias for all you have done for this community in general and my two children, in particular. Quedo en su deuda.” The school was mutually beneficial to the children, families, and teachers who participated in the Escuela. But the school only lasted two years, total. During that time, it provided a free and reduced lunch program, school credits, educational materials, and transportation.

In Voces del Pueblo, just above Noel Márquez’s painting entitled “Nuestras raíces” (1990) is a quote attributed to Quintin González that says, “Not all Chicano activists are artists, but all Chicano artists are activists.” The impact that participating in the Chicano Movement at New Mexico Highlands University had on this group of artists is undeniable—and Medina continues to use her art as activism to this day.

As a student at Highlands in the early 2000s, there were things I could not understand about Chicana/o activism on campus during the 1970s, but I better understand now that I work at the University of New Mexico. Voces del Pueblo, and especially Medina’s photos, deepened my understanding of the significance of Highlands within the greater Chicano Movement. Her photos document the presence of women andchildren working to create and institutionalize a curriculum in which students learn to protect and project their culture. Voces del Pueblo is a reminder of the importance of educating students about their homeland, people, and ways of life.

In Rudolfo Anaya’s novel, Heart of Aztlán, written during the Chicano Movement but set in the 1950s, one of the characters says, “I believe in revolution, like Lalo believes in revolution, but I think the revolution will be done by educating our children. Later, they will return to help us, in their own way they will return to work for our good. I trust in that.” I, too, trust that university spaces have been and can continue to be revolutionary spaces where we will neither be punished nor made to kneel down and beg forgiveness for speaking Spanish or practicing our cultural values.

—

Myrriah Gómez earned her bachelor’s degree at New Mexico Highlands University. She is an associate professor in the Honors College at the University of New Mexico and the author of Nuclear Nuevo México. She thanks Dr. Ray Hernández-Durán, Juanita J. Lavadie, Francisco Lefebre, Adelita M. Medina, and Dr. Irene Vásquez for sharing their time and knowledge with her.