Roads of the Dead

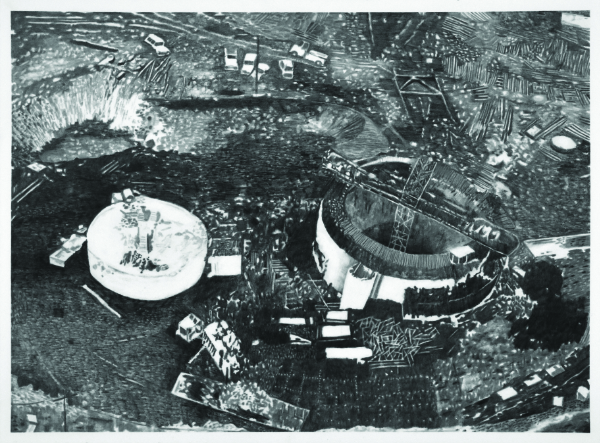

Construction of Titan Missile Intercontinental Launch Site (undisclosed location, pre-1961), 2013. Graphite and radioactive charcoal on paper. Albuquerque

Museum, museum purchase 2017, General Obligation Bonds, PC2020.9.5.

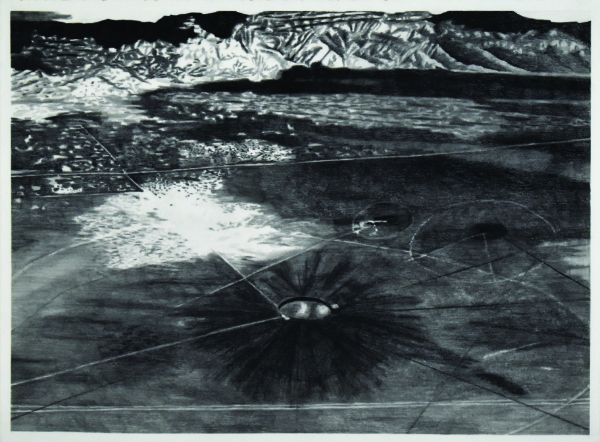

Construction of Titan Missile Intercontinental Launch Site (undisclosed location, pre-1961), 2013. Graphite and radioactive charcoal on paper. Albuquerque

Museum, museum purchase 2017, General Obligation Bonds, PC2020.9.5.

By Daisy Atterbury

Art by Nina Elder

I’m going to Spaceport America.

To access the spaceport, I’ll have to cross the Jornada del Muerto, a desert basin cut by a hundred-mile road. I calculate and the Jornada del Muerto is longer than the distance between the edge of space and my body on land. Trace one expanse, maybe you’d carve across another.

The Jornada has been mapped many times, including by Google. The online map’s layers include Satellite, Transit, Traffic, Biking, Terrain, Street View, Wildfires, and Air Quality. As you approach the area on screen, its layers reveal details.

Some few users have accessed the volcano and comment, Scenic, with a geotag. A user with a sad emoji suggests that the road’s proximity to the Trinity Site, where the first atomic bomb was detonated, gives the Jornada its name, Road of the Dead. Another suggests the name long pre-dates this explosion.

According to the Bureau of Land Management, the Jornada Wilderness Area is almost entirely composed of lava flows that are characterized by lava tubes, sink holes, and pressure windblown sand and clay materials, which support a variety of grass species and soaptree yucca. The area is also home to many species of dark reptiles and a large population of bats that live in a lava tube extending from a crater.

I recall the story of Raffia, a camel who carried a camera across the Liwa Oasis in Abu Dhabi to capture terrain on video for Google Maps. When you look up videos of Raffia’s footage, all you see are trains of more camels. I imagine the Jornada’s dark reptiles. What could these be? Are they on Street View?

I want to tell you:

The name Jornada del Muerto was given by Spanish conquistadores crossing south to north in retreat during the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, one of this continent’s first of many highly coordinated social revolutions.

Now the road is only crossed by a few people, including tourists.

You would quote Lauren Berlant:

No one wants to be a bad or compromised kind of force in the world, but the latter is just inevitable… The question is how to develop ways to accentuate those contradictions, to interrupt their banality, and to move them somewhere.

This person’s coping is difficult to distinguish from an exterminating impulse. This person’s ledger doesn’t add up. If the constraint is a kind of boundary, then why is it so maximally invasive?

We become identified with a wound, you said, and I am like, sure, let me. I persist in autobiography.

Dear __________________,

Can I tell you about driving to Spaceport America? I want to take you to the site of my nightmare. To fill the seepage holes in me with the excesses in you. I want my nightmare to be your nightmare so we can finally see. Backscatter

The Belt of Venus, also called Venus’s Girdle, is an atmospheric phenomenon visible shortly before sunrise or after sunset, during civil twilight. It’s the pinkish glow that surrounds an observer, extending roughly ten to twenty degrees above the horizon.

My windshield looks like paintings or a dry erase board. I take a photo, post it on my story, forty-five minutes from the end of my drive. I’ll park, stay the night, get on my tour. I’ll probably text, or maybe I won’t.

I’ll definitely compose a text. Will I send?

Here’s a photo of an alien sticker on the back of some guy’s trailer.

You like this.

I could write volumes.

In March of this year, I pulled up YouTube Live to watch Falcon 9’s launch of the Iridium-5 mission, SpaceX’s tenth flight of a previously flown (recycled) rocket. Ten satellites were to be delivered and deployed to low-Earth orbit for Iridium, a satellite constellation.

Iridium, the only satellite network that allows you to send out an immediate SOS from anywhere on Earth.

I’d heard about Iridium flares, where the sun reflects off one of the satellites’ flat, door-sized antenna arrays in the exosphere. These are sometimes visible in one bright flash from the ground. A man who worked at NASA once said, I saw one by accident. It looks like a police spotlight, WAY up there.

I wish to see one for myself—a seconds-long burst of police that outshines the planet Venus.

Back in the spring, I watched comments roll as the Iridium-5 launch mission counted down on YouTube. Anticipation seemed to turn to boredom as the time rolled on. But then the rocket’s wings came out. The mood shifted. Comments took a dark, frantic turn.

Don’t blow it up. Pray for them. Avatars hedged and fussed.

As I drive, I review in my head the various offerings available to the dead at Spaceport America. I’d read on Spaceport website that these unique funeral services are available to honor loved ones with a far out sendoff.

You can purchase the Earth Rise Service, which allows you to send a symbolic portion of your dead loved one into space. They experience zero gravity and are returned to Earth.

You can purchase the Earth Orbit Service, which places your loved one in orbit on the Celestis rocket where their DNA floats until it reenters the atmosphere burning up on entry and costs a little more.

You can order the Luna Service, which places your loved one’s cremains on the moon, the surface of our nearest neighbor, and costs a little more.

$12,500 is somehow less than I expected. Two cars in the rearview, I imagine funeral services that could be ignited by Celestis Memorial Spaceflights.

In a serene and dry, modern setting in the New Mexico desert, family and friends gather at the carefully chosen launch site. Anticipation is palpable, mingling with a sense of sorrow and wonder. The surroundings are serene under a breathtaking, unending sky. Attendees find solace in the beauty and tranquility of the notion of the cosmos. Guests prepare to bid farewell to their loved one.

The service begins with a procession, with attendees walking together in unity towards the launchpad. As the group approaches, gentle music fills the air. Adorned with the Celestis insignia and personalized tributes, the waiting rocket stands ready, a symbol of remembrance and also hope, for a future beyond this world. A speaker steps forward, offering comforting words and reflections for a life departed. The speaker shares memories, and anecdotes, all positive. These stories evoke tears and smiles. A vivid picture is painted of the beloved. The speaker’s voice resonates, carrying their words as waves across the launch site and through the atmosphere.

My great-aunt was a rancher in La Madera, New Mexico. I remember my great-aunt’s memorial. Her childhood asthma brought her parents west for the air, then brought my grandparents, my parents. These are colonial stories, familial, personal, historical, social, structural. Neighboring ranchers called my great aunt, Doña Jona. And also, Crazy, loca. She was never far from her shotgun.

Joan Atterbury ran three hundred head of cattle across hundreds of acres of juniper forest for most of her life. She married her ranch hand. As a younger woman, she was raped on the side of the road by a group of men passing in a car. As children, we sprinkled her ashes on the dirt ground of her ranch in the shape of a long cross.

I don’t know what to do with these stories. So many communities’ relatives have walked these lands. I drive, asking what rites have ushered them through this here, if not also beyond?

To think—already, some beings are being sent skywards, not returning to the Earth.

Perhaps for an extra fee, a visiting astronaut follows.

Perhaps, this astronaut offers a speech describing the science and miracle of liftoff.

At the moment of ignition, the Iridium-5’s Falcon 9 rocket engines, pixelated, roared to life on my screen. In the browser’s lingering feed, flames erupted from rocket base. Billowing clouds of smoke and steam engulfed the launchpad.

Watching the livestream, I’d wished hard at that moment for some newsreel—some teleprompter, or polyphonic chorus— put together a meaningful narrative. Not the emoji, or the rush of hearts, but some words, maybe a story of the complexities of occupancy and occupation; a text box, a tickertape; a convulsion of new narratives.

The Belt of Venus is like the alpenglow visible near the horizon during twilight, a backscatter of reddened sunlight so familiar it hardly bears remark. I’ve seen it included by happenstance, on nearly every painting of a mountainscape, sunlight scattered by fine particulates causing the rouged arch of the Belt to shine high in the atmosphere after sunset or before sunrise.

Miles on, the painting in my windshield becomes less lineated. Figures or shadows dance convex on its plane.

Es freue sich

Wer da atmet im rosigten Licht.

Let him rejoice

Who breathes up here in the roseate light.

What the Boundary

A particle, even an association, can flash into being, dissolve, then flash over there.

–Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, from A Treatise on Stars

I might’ve described our separation in terms of star death. You might’ve said my address was never directional. Barthes writes of ravishment, ravissement. I don’t know where to go from here having disembarked again. I sit at this threshold of change with a desire to be unknown.

The sky this far south is less hazy with smoke from smoldering northern forest fires. Still, I think about contaminants.

aaronseyer: The real “Rocket Man”!

levarforever: I’m so sad I missed the live stream

haljordan70: That’s great can’t wait till there is a manned mission

andyglatfelter: They said it couldn’t be done. Now 10x!!!!!!!!

multipole: Soon it’ll be hundreds, and then thousands

caindacosta: i want to get away i want to fly away

realjdcope: The future is here!

The U.S. Government’s Office of Nuclear Energy at present lists three reasons why we don’t launch nuclear waste into space.

1. It’s very expensive

2. Space is complicated

3. Rockets are not perfect

Finally:

It is not worth risking rocket failures when we already have safe and secure ways to store spent nuclear fuel right here on Earth.

In 1978, NASA published a technical paper titled Nuclear Waste Disposal in Space. The paper begins, The disposal of certain components of high level nuclear waste in space appears to be feasible from a technical standpoint.

The paper goes on to clarify that disposal of all high-level waste is, in fact, impractical, because of the high rocket launch rate required and the resulting economic and environmental factors. A separation of waste product, specifically unused uranium and cladding, might make storage of waste feasible on the surface of the moon or in solar orbit.

Remote mining techniques could be employed to recover the waste from the lunar surface.

In her study Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country, Traci Brynne Voyles writes about Indigenous and rural working-class communities who have borne the burden of nuclear weapons development in the southwestern U.S., starting when the U.S. Army began mining plutonium and uranium for use in atomic weaponry during WWII, and continuing with the present-day burial of transuranic nuclear waste in rural, wastelanded regions of the southwest.

waste (adj.) 1300, of land, “desolate, uncultivated,” from the Anglo-French and Old North French waste (Old French gaste), or from Latin vastus “empty, desolate.”

Masahide Koto writes, the primary targets [of nuclear warfare] … have been invariably the sovereign nations owf Fourth World and indigenous peoples. She lists nuclear warfare sites, most coded as tests—the start-to-finish detonation of nuclear weapons in the world.

Marshall Islands: sixty-six times

French Polynesia: 175 times

Australian Aborigines: nine times

Newe Segobia (the Western Shoshone Nation): 814 times

Christmas Island: twenty-four times

Hawaii (Kalama Island, also known as Johnston Island): twelve times

Republic of Kazakhstan: 467 times

Uighur (Xinjian Province, China): thirty-six times

Trinity, New Mexico

Radiation knows no semantics, and contagion knows no rhetoric. The military deployment of weapons, whether labeled test or strike, has all the effects and conditions of warfare unleashed upon the land and peoples it touches.

Water from the well tapped at my grandparents’ land has been found to contain uranium at four times the volume recommended by the health department for safe consumption. We arrive at thresholds, look at patterns, wonder about safety. My mom gets cancer. It’s probably from something else.

Elizabeth Povinelli writes, Familiarity breeds this nervous system.

On January 29, 1951, Geiger counters at the Eastman Kodak Company’s film production plant at Lake Ontario detected high levels of radiation as snow fell around the city. Six years earlier, just after the July 16, 1945 detonation of the first atomic weapon, known as the Trinity Test, Kodak experienced significant financial loss after receiving reports that their film rolls were coming out cloudy.

The company registered a complaint with the National Association of Photographic Managers, who telegrammed the Atomic Energy Commission. Tests snowfall Rochester Monday by Eastman. Kodak Company give ten thousand counts per minute, whereas equal volume snow falling previous Friday gave only four hundred. Situation serious. Will report any further results obtained. What are you doing?

The Atomic Energy Commission released a statement to the press. Investigating reports that snow fell in Rochester was measurably radioactive.

My mom’s uterine cancer requires radiation. I touch her back as she hears this at the doctor’s office. The problem, she tries to explain, is that she knows too much.

I look into calculating my annual radiation dose on a typical year, an idea I get from the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The tab says Radiation is All Around Us.

It’s a strange body feeling to attune oneself to a number.

It seems we live in a radioactive world, that radiation has always been constitutive of our material surroundings. I calculate my cosmic radiation, from outer space, which at sea level is only twenty-six mrem. At 7,000 feet where I live, this number is between forty and fifty mrem. I calculate my terrestrial radiation from the ground. A state bordering the Gulf or Pacific coast is exposed to twenty-three mrem. The Colorado Plateau area around Denver is exposed to ninety mrem. Everywhere else clocks in around forty-three mrem.

If you live in a stone, brick or concrete building, add seven mrem.

If you eat food and drink water, add forty mrem.

If you breathe the (radon in the) air, add two hundred mrem.

If you travel by jet plane, have porcelain crowns, wear a luminous wristwatch, use luggage inspection at the airport, watch TV, have a smoke detector, wear a plutonium-powered cardiac pacemaker, live within fifty miles of a nuclear power plant, or live within fifty miles of a coal-fired electrical utility plant, add more mrem. I do my best, and come out with 410.01 mrem, a number I have no emotional relationship to. This calculation feels like it betrays me, like everything I’ve heard about radiation’s destructive potential is wrong. Radiation is All Around Us.

According to the chart, natural radiation sources account for about eighty-two percent of all public radiation exposure. Man-made radiation sources account for the remaining eighteen percent for a typical person.

Executives at the Kodak Company, after their complaint following the secret detonation of a one-kiloton nuclear device, code name Able, at the Nevada Proving Ground, were granted “Q’’ clearances to receive information in advance of atomic tests to alter plant operations and protect film merchandise, so the company could secure profit margins despite radioactive fallout.K O D A K (1892)

You Press the Button, We Do the Rest!

Communities living downwind of the nuclear test sites were never given a warning.

The atomic story is one of tapping into, and harnessing, a destructive universal force of radiation, of matter’s self-immolating potentiality on Earth. The story goes, we’ve mastered it. But there is only story, itself a drive, and the inevitable unleashing of force, a narrative entropy that unspools in place.

The occupational exposure limit for radiation is 5,500 mrem per year. An occupational dose of 1,000 mrem increases the chance of eventually developing a fatal cancer.

The detonation of atomic weapons and the mining of heavy metals for their production is a known cause of harm for humans and various ecological receptors.

Radiation is all around us. One story betrays another.

_

Daisy Atterbury has written for publications including The Paris Review Daily, BOMB, and The New Yorker online. Currently teaching in American Studies and the Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies Program at University of New Mexico, Atterbury’s work investigates queer life and fantasies of space and place, with an interest in unraveling colonial narratives in the Southwest. This excerpt is from The Kármán Line, published by Rescue Press in 2024. The Kármán Line was a St. Lawrence Book Award Finalist and is described as “a new cosmology” (Lucy Lippard) and “a cerebral altar to the desert” (Raquel Gutiérrez).

Established by the New Mexico State Legislature in 1986, the Art in Public Places (AIPP) program sets aside one percent of state capital outlay funds for the acquisition or commissioning of original visual artwork for public buildings and sites across the state. Since then, AIPP has placed over three thousand artworks across all thirty-three counties, enriching communities with innovative public art that reflects New Mexico’s cultural diversity, as well as regional and national artistic excellence. The AIPP program is one of many arts and culture services serving the creative sector as the State Arts Agency within the Department of Cultural Affairs.

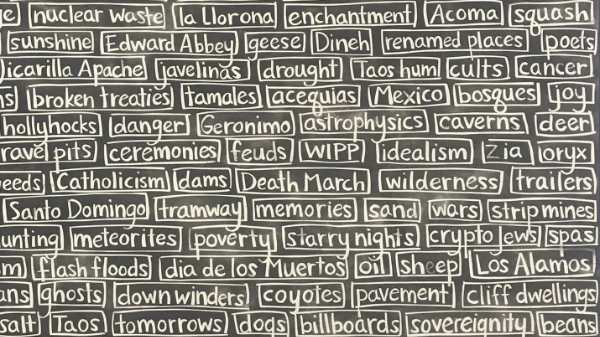

Nina Elder’s artwork has been acquired through the AIPP program historically, and most recently for the permanent collection. An Incomplete List of Everything in New Mexico is currently on display at the New Mexico Arts offices in Suite 270 in the Bataan Memorial Building in Santa Fe.