The Beautiful City of Tirzah

1. Brad Wilson, Western Screech Owl #1, 2011, pigment print mounted on board, 20 × 29 in. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Museum purchase with funds from the New Mexico Photo Council, 2019 (2020.21.1). © Brad Wilson.

1. Brad Wilson, Western Screech Owl #1, 2011, pigment print mounted on board, 20 × 29 in. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Museum purchase with funds from the New Mexico Photo Council, 2019 (2020.21.1). © Brad Wilson.

By Harrison Candelaria Fletcher

Animals come after my father dies. Dogs. Cats. Ducks. Geese. A goat. A peacock. They wander to our North Valley home several years into his absence—appearing on our doorstep or catching our eye from feed store cages. Always, we take them in. We line our laundry room floor with old bath towels, fill cereal bowls with tap water, then flick off the ceiling light to watch them sleep.

“Strays make the best pets,” my mother tells the five of us kids. “They won’t leave.”

In memory, I see this: Beggar’s Night, 1970. My big brother is late. Again. Our mother said he can play after supper on the ditch bank behind our house and to see if neighbors will give him Halloween candy a day early, but when I peek outside to check on him, the sun has already set. Shadows drip like blue ink from the cottonwoods. But I don’t say anything to our mother, who sits in her antique rocker tapping a Russian olive switch on the floor. I scoot on my knees across the hardwood to take my place before the living room TV, where my three sisters huddle before the movie of the week, Dr. No. It’s a school night. We’ve changed into our flannel pajamas. Our hair is damp from the bath.

“Mom!”

The back door thuds open. My brother clomps through the kitchen, breathing hard as if he’s been running. Our mother stands, grips the switch, and intercepts him in the dining room. The overhead light flicks on, bright as an interrogation lamp.

“Wait!” my brother pleads. “I found something. Look!”

I scramble to my feet and jockey for position with my sisters.

Our brother reaches into his brown corduroy jacket, extracts a small bundle, opens

his hands.

A baby bird squints at us.

“An owl,” mother says, setting aside her switch. “It’s adorable. Where did you find it?”

My brother had been hurrying home along the acequia when he heard a rustling from the bushes. When he slid down the embankment to investigate, he startled a hatchling that skittered through the dirt but couldn’t fly. He thought it might have broken its wing, so he scooped it up.

“I looked for the nest but couldn’t find it,” he says, shifting his weight from one foot to another. “Then I saw its mama by a tree. Someone shot her or something.”

Our mother holds the owl to the warmth of her body.

It looks up at her and blinks.

An ornithologist who lives down the street tells my mother we’ve adopted a screech owl, probably a female, he guesses, given the description over the phone. Although it’s not allowed under City of Albuquerque codes, we can probably nurse the chick until she gets stronger. Feed her bits of stew meat, he advises, and later mice. Keep her in a cage or an enclosed room. And watch out for cats.

My mother follows every instruction but one: the cage. She wants the owl to fly freely in her home. She retrieves a cardboard box from behind Safeway, lines it with newspapers and old towels, and places a piñon branch inside as a perch. Then she sets the whole thing on the dining room pottery case, which our tabbies can’t reach.

The owl is the size and shape of an upside-down pear. Her feathers are gray with black-and-white speckles. She has two tufts on her head that look like ears or horns, and her beak is as sharp and shiny black as her talons. What I like best are her eyes, piercing yellow, the size of dimes. When she looks at me, it’s like she’s reading my mind, or seeing something I can’t. One of my aunts won’t meet her gaze. The owl’s eyes, she says, are too human.

My mother considers the bird’s name carefully. Usually, she names the pets after artists or literary figures she admires, like Toshiro, the Japanese actor, for the silky black-and-white cat. Sometimes she chooses characters from her favorite films, like Tonya, from Dr. Zhivago, for the German shepherd.

For the owl, though, my mother decides on Tirzah.

“Tirzah,” she says, savoring the syllables, which break like the morning light through her bedroom window crystals, turquoise and gold. “My little Tirzah.”

“What’s it mean?” I ask, watching her stroke the bird.

“It’s an old name. A religious name. From the Bible.”

Later, I look it up in the library.

“Tirzah—A city in Palestine, a beautiful place alluded to in the Songs of Solomon (`You are as beautiful, my darling, as Tirzah’).”

Each morning, my mother sets the owl’s box on the dining room table while she makes breakfast, sketches, or pays bills. Tirzah hops out from her box and waddles over to nibble my mother’s pen. If she leaves the room, the owl scurries after her. The only way my mother can finish her chores is to wrap the fledging bird in a washcloth and tuck her in the breast pocket of her denim work shirt.

Tirzah remains there for hours, lulled by my mother’s heartbeat.

On Sunday evenings, my grandmother, Desolina, stops by our house for pot roast stuffed with garlic. Over supper, she grumbles about her childhood in Corrales, growing up among horses, cows, and chickens in a drafty adobe where black widow spiders dropped from the rafters into her tin cup of milk or coffee. She hated every minute of it, she says, but learned the old ways despite herself. She knows how to bleed a goat, how to age red wine, and how to treat a rattlesnake bite with chewing tobacco. And she knows about spirits. While my mother collects the supper dishes, I line my toy knights on the table and listen to the two of them whisper in Spanish about dead relatives. When Desolina catches me eavesdropping—she always catches me—she laughs under her breath and beckons with a crooked finger. “Come here, mi’jito,” she says, leaning from her chair.

Then, in a low raspy voice, she describes the fireballs dancing along the Rio Grande bosque, the footsteps dragging down her hallway at midnight, and the crone who transformed into a banshee to chase her brother home on an acequia near Bernalillo.

“It’s true,” she says, nodding at my wide eyes, then breaking into a smile. “And did you go to church like I told you?”

When Tirzah flutters by, my grandmother makes the sign of the cross. Owls, she always says, are bad omens, messengers of the night.

“Que fea,” she mutters. “Why did you bring that ugly thing in your home?”

My mother shrugs. “I think she’s beautiful.”

When Tirzah settles on the back of a chair across from her, Desolina holds the owl’s gaze for a full thirty seconds. She slips a glow-in-the-dark rosary from her purse, turns her head, and spits.

I don’t go camping, like the other kids on my block. I don’t go fishing, boating, or even to Uncle Cliff’s Family Land. My mother doesn’t like tourists. Doesn’t like doing what everyone else does. Instead, on weekends, we go exploring. We pile into her peacock green `67 Comet and hit the road.

We visit old churches, abandoned graveyards, ghost towns, and adobe ruins, chasing a landscape and culture she says is vanishing before our eyes. She talks to old people, scours the ground for roots and fossils, and collects antique tables and chairs, while I run with my siblings through the juniper and pine playing Last of the Mohicans.

One Saturday morning, washed clean by spring rain, we pile into the bed of my grandfather’s F-150 and head north to Truchas, a village so high in the Sangre de Cristos we almost touch the clouds.

In a roadside meadow, my grandfather, Carlos, notices a slice of aspen bark—eight feet long, crescent shaped, with a knothole at one end. My uncle, who’s come along for the ride, says it looks like a cobra. I see a dragon. My mother says it has “character,” so we pitch it in the truck.

Before heading back to Albuquerque, we stop at a tiendita for gas, chile chips, and root beer. The viejo behind the counter tells us the bark was cut by lightning a few nights earlier. He saw the flash himself, heard the thunderous boom. This makes my mother smile.

Back home, she nails the plank across the living room wall. Tirzah notices immediately. She flies out from the dining room pottery case and claims the perch as her own, sliding down the arc to the knothole at the bottom, watching us through the dragon’s eye.

The owl isn’t my pet, although I’d like her to be. She won’t come when I call, perch on my finger, or take meat from my hand, as she does with my mother, uncle, or brother. It’s not that I’m afraid. It’s more that she’s too beautiful to touch. When she does approach me, I get nervous, and she flies away.

One afternoon, though, while I’m doing homework, Tirzah flutters down beside me onto the dining room table.

“Hi, pretty girl,” says my mother, who sits beside me sewing a blouse. “Are you thirsty?”

Tirzah waddles up to me, ignoring the water bowl my mother slides forward.

I tap the pencil eraser on my teeth.

“Go ahead,” my mother says. “Pet her. She won’t bite.”

“I know, but she doesn’t like me.”

“That’s not true. Just scratch her head. She loves that. Rub in little circles.”

I extend the pencil.

Tirzah flinches, eyes wide, preparing to fly.

“See,” I say, withdrawing my hand. “She hates me.”

“Wait,” my mother whispers. “Try again. Slower.”

I inch the eraser forward until it touches the owl’s head.

Tirzah squints but stays put.

“Use your finger,” my mother says. “Like that. See how funny it feels? Like a ping pong ball?”

Tirzah closes her eyes and leans into the pressure.

The more she relaxes the more I relax.

After a few minutes, the owl curls her toes and rolls onto her side, asleep.

My grandfather Carlos visits us on his way home from the highway construction crew. At sixty-five, after raising nine children and working all his life in construction, he insists on holding a job. He nods hello to us, settles into a corner rocker, and hangs his gray fedora on his bony knee while my mother fetches him a cold Coors longneck.

Carlos doesn’t talk much. He prefers to watch, listen, and absorb the warmth of a family life he never had as a boy. His father died when he was eight. When his mother remarried, her husband refused to raise another man’s son, so she sent him to a boarding school in Santa Fe. He ran away with a friend soon afterward, walking a hundred miles through the Rio Puerco badlands to the village of Marquez, where he worked handy-man jobs. Carlos slept in arroyos, caves, and abandoned barns during that trek through the chamisal and cholla. On those lonely nights, he told my mother, owls watched him from the junipers, bathed in silver moonlight.

One night when he stops by our house, Tirzah glides down to his armrest from her aspen perch. When Carlos extends a gnarled finger, she hops on. He raises her to his nose, and smiles.

Each winter, our house fills with the sweet scent of piñon. We have no fireplace or wood-burning stove, so my mother sprinkles trading post incense over the steel grate of our living room floor furnace instead. It reminds her of childhood on the rancho in Corrales, she says, crumbling sawdust between her fingers, then standing in the heat as sparks swirl before her eyes. As a girl, she stoked the potbelly stove in her grandmother’s kitchen. Piñon smoke reminds her of black coffee in tin cups, cotton quilts, and crackling horno flames. Piñon smoke takes her back, she says. All the way back.

When my mother leaves to prepare fried potatoes and green chile for supper, I take her place on the furnace vent, standing in the current until my blue jeans burn my legs. As Tirzah glides by, white smoke curling from her wings, I imagine I’m soaring through the clouds beside her, drifting like an apparition above the antique tables, Navajo rugs and clay pots, haunting this

room forever.

On nights before art show openings, I sleep to the hiss of my uncle’s propane torch and the click of his sculptor’s tools. He’s the youngest in my mother’s family of nine, fourteen years her junior. He moved in with us four years after my father died. My mother needed help around the house, and didn’t feel safe alone with small children on the farming edge of northwest Albuquerque. She also wanted a male role model for my brother and me, although my uncle is barely out of his teens. He listens to The Doors, Jimi Hendrix, Country Joe and the Fish. He has a wizard beard and shoulder-length hair and walks barefoot everywhere, even in the mountains. I think he looks like George Harrison stepping onto the crosswalk of my mother’s favorite album, Abbey Road, but my grandmother thinks he looks like Jesus. Desolina wants him to be a priest, to help atone for family sins, but he’s an artist, instead. With needle-nose pliers and rods of Pyrex glass, he creates intricate figurines of Hopi eagle dancers, Mexican vaqueros, and Navajo shepherds, then mounts them on driftwood and volcanic rock. I watch him from my pillow with his Einstein hair and welder’s glasses, crafting icy figures from fire. Tirzah perches above his worktable, drawn, like me, to his clear blue flame.

My brother finds most of our strays. Or they find him. He’ll see a German shepherd digging in the garbage, walk right up, and it’ll lick his hand, a friend for life. He has a way with animals, which soothe him in a way no one else can. He was six when our father died. He has the most memories.

He and I are polar opposites, our mother likes to say. And she’s right. My brother loses his temper like the strike of a match and plays hardball without a glove. I’m steady, docile, and brooding, like my duck, Hercules, with his blunt beak and orange feet, content to never leave his yard.

On weekday afternoons, Tirzah waits by the front window for my brother to return home from school. She hoots when he shuffles through the driveway, flies to his room while he changes from nice clothes into blue jeans, and perches patiently on his shoulder while our mother tethers them together with a strand of yarn—from boy’s wrist to owl’s leg.

Task complete, they step outside to straddle his purple Sting-Ray bike. I watch from the front porch steps as they pull away, Tirzah’s eyes swallowing light and motion—flashing chrome handlebars, fluttering cottonwood leaf, the neighbor’s dog yapping behind a chain-link fence.

“Be careful,” our mother shouts, but my brother stands on his pedals anyway, and steers a wide circle under the streetlight, gathering speed for the racing lap around the block.

Tirzah grips his jacket and leans into the wind.

My mother wants to bless our pets. Although she took a hiatus from the church a few years after my father died, she wants protection for our strays. So, on a warm Sunday in February, we load the ducks, geese, peacock, goat, and owl into our Comet, and attend the outdoor ceremony in Old Town.

We stand in line behind a few dozen puppies, kitties, gerbils, and bunnies. The priest chuckles from the white gazebo in the plaza as he sprinkles holy water. When our turn arrives, he stops mid-motion and appraises us behind silver-rimmed eyeglasses. My brother slouches before the dais, arms folded, Tirzah on his shoulder. I kneel beside the black Nubian goat, which suckles from a baby bottle. My oldest sister cradles the peacock, while the other two hold a mallard duck and a snow goose. Our mother lingers on the steps, eyes hidden behind her Jackie O sunglasses.

We’re longhaired, tie-dyed, and proud of it, in full bloom eight years after my father’s funeral, surrounded by the animals that brought new life into our home.

Parishioners scowl. A poodle yaps. A news photographer snaps our portrait.

After a pause, the priest mumbles a prayer.

The next day, we make the front page.

Tirzah surprises us. When one of the dogs slinks through the house, she contracts her feathers, squints, and becomes as thin and gnarled as a dry juniper branch, invisible against the gray of her aspen plank. She can change direction in mid-flight, too, hovering in place like a helicopter, swiveling her head, then returning silently the way she came. She’s also a stone-cold hunter. When we place a chunk of stew meat on her perch, she puffs up to twice her normal size, dilates her pupils wide, and pounces. She thumps the meat several times, then flings it to the floor. Yellow eyes blazing, talons scratching hardwood, she stalks her meal like a panther. Finding it, she opens her beak, swallows it whole.

During the day, the sun is too bright for the owl’s sensitive eyes, so she seeks dark corners to sleep. One morning, when the temperature hits eighty-nine, my middle sister reaches into the hall closet to flick on the swamp cooler but leaves the door ajar. The chain is broken on the overhead bulb, so the closet is always pitch black. Tirzah, gazing toward the opening from her perch, flutters atop the closet door. I hold my breath. My sister calls our mother. Normally, the closet is off limits to us kids and the animals. We try to shoo Tirzah away, but she won’t budge. She just stares into the cool abyss. After a moment, she lowers her head and hops inside. From then on, the hall closet becomes her sanctuary. To fetch her at feeding time, I must reach into the darkness, brushing my father’s things.

Breaking the Mold

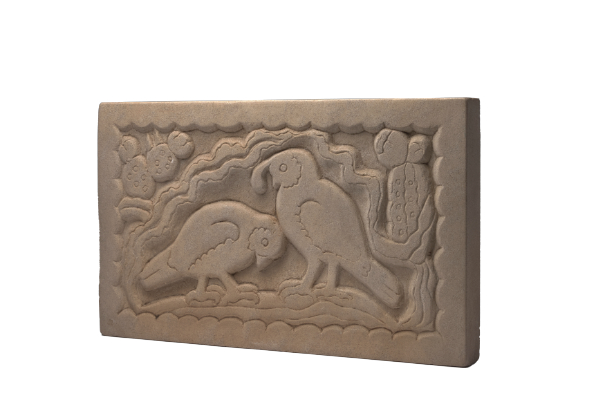

The animal-themed art that appears alongside Harrison Candelaria Fletcher’s essay—apart from the screech owl—is the work of Eugenie Shonnard. Eugenie Shonnard: Breaking the Mold opens at the New Mexico Museum of Art March 8, 2025, and is the first major posthumous exhibition of the acclaimed sculptor. Shonnard was a pivotal figure for the history of art and sculpture in the Southwest, widely recognized during her own time for her contributions to the visual arts, yet largely overlooked in recent decades. This exhibition, with an accompanying publication, seeks to reintroduce Shonnard to a new generation of art enthusiasts. The images in this article belong to the Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art, and were a gift of the Eugenie F. Shonnard Estate, 1978. © Museum of New Mexico Foundation.

Shonnard’s subject matter reflected her interest in the distinctive cultures she found in New Mexico, and she soon earned a national reputation for insightful depictions of the folk traditions of the Southwest.

Shonnard worked across a wide variety of sculptural techniques, but came to champion “direct carving,” also referred to as taille directe, which was popular among early twentieth-century sculptors. This approach to sculpture involves working directly on a sculpture without the use of models or maquettes for reference, making many of her sculptures one-of-a-kind objects.

Eugenie Shonnard: Breaking the Mold emphasizes the breadth of Shonnard’s long career, from her early Art Nouveau designs created under Alphonse Mucha’s direct influence to the sculpture, architectural ornaments, and furniture she produced as a mature artist. The exhibition closes August 24, 2025.

—

Harrison Candelaria Fletcher is the author of Descanso for My Father (2012), Presentimiento (2016), and Finding Querencia: Essays from In-Between (2022). He is the recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, MacDowell, and Helene Wurlitzer Foundation, as well as the Autumn House Press Nonfiction Prize, Colorado Book Award, and New Mexico-Arizona Book Award. A native of Albuquerque, he teaches at Colorado State University.

“Beautiful City of Tirzah” is adapted from Descanso for My Father: Fragments of a Life by Harrison Candelaria Fletcher by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. Copyright 2012 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska.