Storytelling Creatures

World Making with Eliza Naranjo Morse

Eliza Naranjo Morse, Light from Love Triptych, 2024, acrylic, glitter, and clay on canvas, 60 x 144 in. Tia Collection.

Eliza Naranjo Morse, Light from Love Triptych, 2024, acrylic, glitter, and clay on canvas, 60 x 144 in. Tia Collection.

By Mariko O. Thomas

In her 1988 collection, Favorite Folktales from Around the World, the folklorist Jane Yolen introduced humans as the primary source of stories, writing that, “Only humans can create tales that change or structure the world in which they live.” However, this statement is challenged by the menagerie of beings which painter and sculptor Eliza Naranjo Morse calls forth in her art. When encountering her luminescent and kaleidoscopic paintings of creatures, it becomes difficult to argue that humans have been the only ones to weft and wend the fabric of stories. We are summoned to question the possibility that these creatures can teach us enough to imagine their tales as interwoven and instructive to our own lives. With almost unassuming deftness, Naranjo Morse’s iridescent teal and purple beetles move with veritable personalities, and the clouds in the sky tell parts of the story—despite the flat planes in which many of her creatures live their lives and play out their narratives. There is something cinematic and deeply animate about the whole affair, like the viewer is entering the world of movement and dreams that are at once a powerful stride into the unknown and deeply reminiscent of an ancestral time when humans lived as tiny players in a more magical and vibrantly alive world.

I get to speak with Naranjo Morse on a day where she is at home, and when the Northern New Mexico air is crisp, with the tickle of autumn unfurling, and after she and her mother have gathered all the tomatoes and peppers from the garden. Word on the street is that her mother makes a mean pepper jelly—and don’t even get her started on the pickled carrots. I am on a video call with her, away from that beloved landscape, so I beg her for details of the season, and we chat about the glowing mats of cottonwood leaves and the sense of completion that comes with winding down harvest season. She indulges me with generous observations of a place we both love, her eyes warm and wide even through the computer screen. She tells me that she has a sincere love for the landscape of New Mexico, and for the soil in this area. Her expression reverent, she says, “I drive by dirt and am like, ‘I love you.’ Pick some dirt up and feel this legitimate reciprocal love.”

Naranjo Morse is from here. Like, deeply from here. On her curriculum vitae, under the education heading, she writes “The ongoing education I receive from my Pueblo elders which spans considerations of language, values, knowledge systems and creativity that is rooted in Tewa worldview as it meets a current global experience.” That kind of from here. The line precedes the list of her formal education and gives her CV an active life force that challenges the sterility of these sorts of documents, and it roots her work in the cartography of mesas and monsoons that make up Northern New Mexico.

Born in Albuquerque with her twin brother and brought back to Tewa homelands, Naranjo Morse remains there to this day. An out-of-commission post office once served as her studio, though now the studio is in the house she and her partner are building, and at the time of my interview with her, they were pushing to get windows installed before winter. She makes her work ensconced in the very community where she was raised, a place where art as a way of life was normalized from her nascency. Naranjo Morse teaches art at the Kha’p’o Community School, is an avid auntie to her nieces, and is also an avid niece to her aunties, with whom she spends a significant amount of time assisting in their projects, accompanying them to do talks on various topics of their expertise, such as relationship and reciprocity. She also supports her mother Nora Naranjo Morse’s work building and sculpting, and is helping to care for Nora’s installation, Always Becoming, at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. From what I can tell, Naranjo Morse is honored to be interwoven in the undertakings of her family. “Sometimes I feel like I need a little headset like a wedding planner,” Naranjo Morse says, laughing. There isn’t an inch of ego or ire in her voice, just a sense of joy that she can be there, and an enviable sense of clarity about her family role and the wisdom of her elders.

This makes sense, as Naranjo Morse’s family provided the first fertile soil in which her artwork began to bud and flourish. From a kinship group comprised of an inordinate number of artists and craftspeople, she says that somebody was always sculpting, making pottery, or drawing; or her mother was gathering random bits and bobs to spray-paint and render into something meaningful. She often handed Naranjo Morse a lump of material with an encouragement: “Here’s some clay, go over there and make something.”

Place in NM (4 May 2018 – January 28, 2019), National Hispanic Cultural Center Art Museum. Photograph by Addison Doty.

Naranjo Morse spent much of her youth making things. She spent a good amount of time with her cousins, building forts from old lumber, elm sticks, and piles of leaves, choosing prime rocks for her “tea kettles,” and making tunnels in the dirt. She also adored involving Trolls dolls (figurines with solid little bodies with wrinkles in their hard plastic foreheads and shocks of hair in neon green or burgundy sprouting out of the tops of their heads) in her childhood art projects. When she summoned these toys into the conversation, she ushered in a whole era of memories. As a child, she loved to use Trolls as the catalysts for creation as she considered what they needed to live out their stories. For example, the Trolls needed a tiny painting next to their cardboard couch (also made by Naranjo Morse), or miniscule cardboard candy. Her adoration for creatures which were not particularly cute nor particularly human makes sense. As her work evolved, it continued to feature sometimes overlooked creatures. From making Trolls rugs and tables, she moved on to drawing people, flowers, worlds, and monsters. She told me that she would, quite literally, draw anything. She enjoyed making comic books and cartoons—anything with a sense of sequence, and to occupy herself, she often played “pass it” with her family; a doodle would be passed from person to person until a story developed organically.

“I knew from my Pueblo family and also my non-Pueblo family that art could be incorporated into every task,” Naranjo Morse says. “All normal activities—from cleaning the yard to plastering the wall with mud—those were all made into normal daily practices as opposed to something at an arms-length, like now you’re doing art.” In a gaggle of tight-knit cousins, the kids went from studio to studio, or house to house, looking for activities and art supplies. Drawing was an activity to which Naranjo Morse dedicated enormous amounts of care and practice. She says the idea of something two-dimensional felt radical, and she wanted to know what stories those flat shapes could tell.

Naranjo Morse remembers a major shift that crept its way into her consciousness when she was around nine. Her uncle, who was blind, was coloring with her in a Gremlins coloring book (other creatures from the 1980s, with similarly wild hair and wrinkled faces). She peered over at her uncle’s coloring page as he made circles all over the page, picking different colors as he went along until the page was a mass of blue and green and yellow swirls, which gave her pause and filled her with wonder. “It was so much more beautiful than trying to color a Gremlin in,” she told me, “The colors were moving around each other, it was significant to my sense of what is possible in illustration—and prescribed systems. It affirmed my sense that art was boundaryless.”

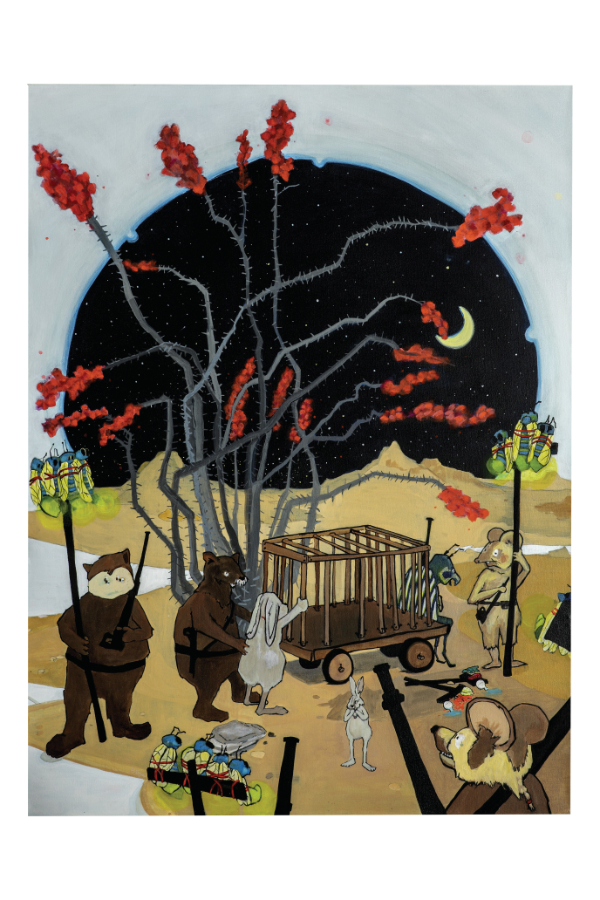

It is clear Naranjo Morse took her uncle’s coloring seriously. Her art practice is wide-ranging, from sculpture and installation to drawing and painting in riots of color, but the most arresting for me are her cartoon-like characters. Some of her drawings feel as if you’ve stepped into a dream of whimsey, but with some serious undertones. In one painting, a frog and a rabbit are in a moment of conflict with an armed beetle which pulls a jail cart—but all under a strangely calming nighttime sky and the shadow of a carmine ocotillo plant. Naranjo Morse notes that as she gets older, she has become more invested in the lives of landscapes and incorporating them as storytelling beings in her paintings, working to give them voices and agency to move and tell the story swirling in and out of the painting. She says,

Landscapes have all of the history; certain hills or mountains have deep meaning for people—they are holders of enormous significance. When I was younger, I was very interested in what people were doing or what was happening so the space was more open, but now [in my current work], how do I make a space that helps tell a story? The New Mexican landscape becomes the most beautiful landscape for figuring out how to do that. Animal-like storytellers are important to me but now it’s like … wait a minute, if I put these Beings next to an ocotillo plant, then I’m able to offer them the same unique medicine that the plant offers. If they are under a quarter moon, then what does it mean about how a story is growing? Or receding if the moon is waning? These details become significant [in order to] love earth and stories, but also to tell a story.

There is a sense of animacy that permeates Naranjo Morse’s work, and she thinks about materials not only in terms of selecting the right medium, but also the resonance of what the vegetables, animals, and minerals can indicate in terms of landscape’s history. Last summer, she started painting amaranth frequently, enamored with the history and significance of the plant. She felt that by drawing amaranth, the plant’s story is acknowledged, along with its perseverance and nutrients. Then, as a byproduct, the human story of our historical relationship with those magenta leaves is revealed. “It’s exciting to begin using plants as storytellers,” Naranjo Morse says. “I’m thinking about the power corn holds as an expression of one’s life going through stages, and how human survival is dependent on the more-than-human relationship not just with the corn harvest, but all the life that made it possible. There’s a kinship that comes with knowing corn through different stages; if the tassels form it means it’s a certain part of summer. And that means a whole environment of experience.” These plant stories become narrative details in her paintings, helping the journey playing out in two dimensions communicate the long relationship between humans and amaranth, or humans and corn.

Naranjo Morse also draws tools. “I like shovels. I like sticks. I like toys, they remind us to … return to a time when we held something so precious,” she says, noting that she watches her little nieces walking around with pouches and purses they fill with small, sparkly things. “They are all precious about it,” she laughs, “and they just have some rocks and maybe a little figurine or notebook or something.”

Naranjo recognizes the ways that these small items which make up our lives can have storytelling significance, and that there is reverence in how children care for the flotsam and jetsam that adults can overlook. In her mixed-media collaboration with Brandee Caoba, Carrying, Collecting, Letting Go, The Feeling of Us,that was part of the exhibition Because It’s Time: Unraveling Race and Place in NM exhibited in the National Hispanic Cultural Center Art Museum from 2018 to 2019, Naranjo Morse depicts a human-like character moving through space and time, carrying and collecting parts of environment and ancestry that make up their own identity—all the precious little bits that allow us to become who we are.

This attention to tiny things is evident throughout Naranjo Morse’s work and approach. For example, she smears in a little slip of clay in all her paintings to remind the paintings that they are connected to the ground, even though the paints themselves contain plastics, as many art supplies do. She takes comfort in knowing the paintings will have a connection to home and a form of grounding, even when mounted on walls away from the place where they were made.

It is often difficult to discuss the concept of animacy without verging on anthropomorphism. It is human habit to project our traits onto more-than-human beings by refashioning them in our own image, but the way that Naranjo Morse interacts with her characters is not quite that. Her work reflects the things humans can learn from other creatures. She draws insects because they tell a story about a more communal way of being. She loves to render badgers and leans into how smart and tenacious they are—not graceful, but hearty and dedicated to getting something done. She draws stars because they are “a reminder that it’s not just us; we’re being held within a much larger natural system; it’s a reminder of what is possible and how connected we are.” She creates with care and a belief that everything deserves to be cherished.

Naranjo Morse’s most recent work in the group show, Vivarium: Exploring Intersections of Art, Storytelling, and the Resilience of the Living World at the Albuquerque Museum was no exception to this care. A vivarium is a clear container where viewers can watch nature. The exhibition simultaneously played with the idea that vivarium means “place of life” in Latin and could be a way of observing or putting the natural world under a microscope. Artists troubled this meaning by providing myriad opportunities to view junctures in human and non-human environments and built and natural spaces. Naranjo Morse, along with a handful of other artists from other Indigenous communities, presented a compendium of approaches as to how the non-human world continues in its resilience. These ideas, which included heavy engagement with animism and mythology, a confrontation of consumerism and environmental neglect, and the uplifting of hope, were meant to foster public dialogue for ecological and societal changes.

The world seems ripe to recognize the timely necessity of Naranjo Morse’s work, as she was recently named as one of The National Museum of Women in the Arts’ “Women to Watch 2024.” When I mention this honor, she smiles and says, “It took me way too long to be brave enough to make the art I wanted to.” She tells me that she had doubts (like so many) about doing her heart’s work, and about whether her creature drawings would be understood as having meaning beyond being cute. “The honor of being selected to represent New Mexico in the exhibit in Washington, D.C. was an affirmation to express my creative truth and be brave about it,” she says. Then, thoughtfully, she expresses gratitude for the chances she has been given and hopes for those same chances for as many young and elder artists as possible. “How can institutions lift as many creative thinkers up and give them as many chances as possible?” she asks. “Because sometimes it takes more than one chance and one person to fully explore what we are meant to share. This helps us and our world so much more.”

I think of this collective approach to living as I sink into her triptych titled, Light from Love. It is a bird’s eye view of deer, birds, squirrels, and all manner of other creatures with brightly colored possessions roped to their backs. They are moving towards an unfathomably deep circle in the center painting, where the galaxy swirls and the sparkle of stars winks up at them, almost as if it were calling them all home after a long day. Whether it is beetles or plants or family, Naranjo Morse is firm on the preciousness of creatures great and small, and her work serves to imagine a world in which all beings are held in an interwoven net of stories and stars.

—

Mariko O. Thomas is an independent scholar, instructor, and writer who moves between Arroyo Seco, New Mexico, and Whidbey Island, Washington. She has a PhD in Environmental Communication from University of New Mexico and researches plant-human relationships, environmental justice, and storytelling. Thomas is also co-founder of an arts and ecology collaborative called Submergence Collective, an associate editor for the academic journal Plant Perspectives, faculty at Skagit Valley College, and pretty decent at reciting fairy tales.