Ritual Killing: Oryx in New Mexico

Photographs and essay by Marcus Xavier Chormicle

As the desert transitions from deep blacks to dim greys and blues, we creep through the mountain pass. We leave the city lights behind us and roll into the dark nothingness. Our headlights rip through the morning and carry us onto base.

Beginning in 1969, oryx were introduced to the Chihuahuan Desert. Frank C. Hibben, a foreigner to the desert himself, brought these aliens onto the land. Released onto the White Sands Missile Range, the largest restricted military airspace in the United States, the powerful creatures quickly grew in numbers and range. The oryx spread nearly as far north as Albuquerque, and to the south past El Paso. Hungry, thirsty, and amorous, they tore across the land.

I don’t remember learning about the oryx. They’ve always been a fixture in my life: Their skulls bleached in the Las Cruces sun in my grandparents’ yard, oryx flesh filling the freezer in their garage, heads racked on the wall in their living room. When I was young, I didn’t have a real concept of what was and wasn’t native. As I grew, I came to understand the pronghorn was, the oryx was not; the ocotillo was, the tumbleweed was not; my father’s parents were, my mother’s were not.

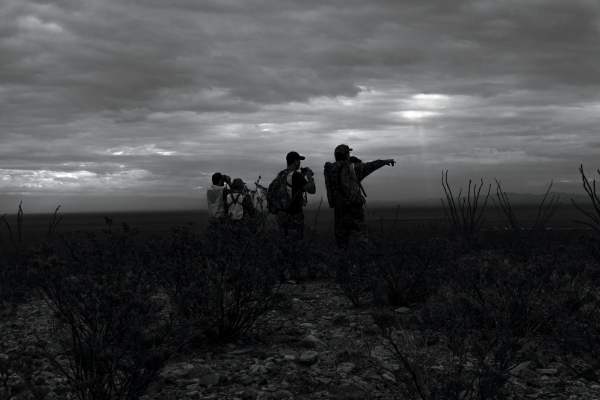

We followed the lines of sand on the desert floor to the base. The driver, a serviceman stationed at the base and the hunt sponsor, called in and listed our names one by one, as clearly as possible. Each of us had to match the list of approved hunters. We were cleared to cross. From the top of the hill, one of the hunters peeked an oryx one thousand yards out. We needed to be less than three hundred yards away to stand a chance of getting a shot. So we stepped out in a neat line to march across the desert toward the beast.

I grew up hearing stories about my grandma Phyllis getting a kill. We were proud—it was a sweet success. I never went on a hunt as a kid. The violence of the Southwest was prevalent in our lives and family history. My parents didn’t like guns, and fairly so. My dad’s father was shot by police and died of his wound. My mom’s brother shot himself in the head when he was five with her father’s gun and died of his wound. We spent at least half our childhoods at our grandparents’ houses but we weren’t allowed to touch their guns.

As we trek toward the hill where we last saw the oryx, I try to absorb the landscape. My photos are a useful tool for remembering, but I want to hold onto this place. Despite growing up less than twenty miles from the site, I had never been allowed to enter White Sands Missile Range, and it’s unlikely that I will again.

It is beautiful here; the desert’s abundance has been preserved by the restriction of access to the land. Thick tangles of ocotillo flourish, bucks with some of the largest horns I’ve ever seen casually pass us by, and the oryx dominate the space. Large herds sprint across their inherited territory, and yet they elude us.

I stand quietly, camera raised to my eye. Through the lens, I watch the hunters peer through their binoculars across the terrain. The oryx come into focus as they weave through creosote. Their horns reach for the sky alongside the spindling arms of the ocotillo. The oryx’s eye fixes on the glint of the hunter’s glass, the hunter adjusts his dial to bring the beast into focus, I squeeze my finger down and shoot; the oryx runs over the hill and is gone into the vastness of the brown desert.

What to do with the oryx? Since its arrival in the desert, oryx numbers have grown exponentially. There are five to six thousand oryx in New Mexico. The animal’s impressive adaptability and resilience have helped it thrive in the ancient Chihuahuan ecosystem. Every year, approximately 1,500 oryx are harvested from the desert, dressed, carried out on hunters’ backs, stuffed into coolers in the back of truck beds, and hauled off the land.

In the 1990s there was backlash from animal rights activists when word got out about the Park Service’s plan to cull problem oryx on the White Sands National Monument. The people of New Mexico stood by their adopted creatures. Now we are past the point of no return; the oryx have made their mark in the desert. The responsible decision would have been to rid the land of them, but the option to maintain the new status quo won out.

As we work our way off the range, after a day of chasing the near mythical creature, I reflect on the frivolousness of maintaining the population this way. We now live in a system of ritual killings to maintain the status quo of the desert, but it is not quite enough. The gas pedal remains flat against the floor.

—

Marcus Xavier Chormicle is a lens-based artist and independent curator from Las Cruces, and lineal descendant of the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians. His work focuses on family, memory, and the intersection of class, race, and history in the Southwest. In 2024, he was a New Mexico Arts artist-in-residence at Lincoln Historic Site where he expanded on his oryx project.