Before the Famous Fossils: Ancient Life in the Paleozoic Era in New Mexico

Ancient Life of the Paleozoic Era in New Mexico

The western slope of the Sandia Mountains exposes 1.4-billion-year-old pink granite, accentuated at sunset. Few places in New Mexico have visible Precambrian rocks. Photograph by Tira Howard, 2021.

The western slope of the Sandia Mountains exposes 1.4-billion-year-old pink granite, accentuated at sunset. Few places in New Mexico have visible Precambrian rocks. Photograph by Tira Howard, 2021.

By Tamara Enz

Talking about ancient life and the Paleozoic Era (252 to 541 million years ago) in New Mexico elicits various unexpected responses. Oh, cool! The ancient Puebloans. Well, no. A little further back. Great! Dinosaurs. Charismatic megafauna get all the press, but no, earlier in geologic time. Occasionally, Oh. I tried that diet. No, again. Long before people living the Paleo diet, those who walked through White Sands at the end of the last ice age, and before New Mexico’s famous dinosaurs, the Bisti Beast and Coelophysis (74 and 208 million years ago, respectively), what we now call New Mexico was a dynamic landscape teeming with life.

Over the last five hundred million years, continents moved, ice ages came and went, sea levels rose and fell, and mountains grew and washed away. Life proliferated and was exterminated in mass extinctions, not once, but five times. This geologic and biologic variety and upheaval left some of Earth’s finest fossil beds in New Mexico, drawing paleontologists from around the globe.

Beyond the famous dinosaur remains, the state has a spectacular array of lesser-known and significantly older fossils. Carefully extracted, described, and cataloged over decades, this extensive collection is at the center of the permanent Bradbury Stamm Construction Hall of Ancient Life, which opened at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science in February.

Matt Celeskey, curator of exhibits, and Dr. Spencer Lucas, paleontology curator, generously guided me through the display and museum collections. “This exhibition is kind of a reimagining of the very beginning of the journey through time,” Celeskey tells me. “Since the museum opened, Spencer and his colleagues have been collecting fossils all around the state and filling our collections with New Mexico’s ancient life, the fossils from the Paleozoic Era, and we’re excited to have the opportunity to really put them on display.”

Lucas adds, “When you visit you will see unique fossils that are only here. It’s not like you’re going to see models and stuff. That’s common. We have a lot of unique fossils that have only been found in New Mexico.”

Ancient Life details approximately 250 million years of the Paleozoic Era. Beginning 541 million years ago in the Cambrian Period, life suddenly diversified from microscopic, mostly single-celled beings to more complex lifeforms, and the fossils these creatures left behind first appear in the rock record during this period. Following the Cambrian, the Ordovician marked a time of ice ages, ending with the first mass extinction. Vascular plants evolved in the Silurian Period, as did fish with jaws and freshwater fish, ushering in the Devonian Age of Fishes. Four-legged creatures evolved from fish and moved onto land in the Devonian. After two mass extinctions, ice ages gripped the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian Periods. Outside of the U.S., these two periods are combined and called the Carboniferous, in honor of carbon in rock form—the world’s coal source—but in North America, the division between the two periods is so distinct that they are separated. The Permian Period marked the end of the Paleozoic Era 252 million years ago with The Great Dying, when ninety-five percent of Earth’s life went extinct, setting the stage for dinosaurs and eventually ancient humans. Presenting New Mexico fossils from each of these periods, Ancient Life shines in the late Paleozoic, with about 75 percent of the exhibition from the Pennsylvanian and Permian Periods.

The Precambrian: 4.5 billion to 541 million years ago or everything before fossils outgrew the microscope

Almost any fossil story must begin with 4.5 billion years of Earth-bound geologic time. The Precambrian encompasses the first four billion years—nearly 90 percent—of the Earth’s history. During the Precambrian, storms raged, land formed, life began, and the early hot and hellish atmosphere of carbon dioxide and nitrogen became oxygen-rich. Earth was in motion. Following a global ocean and bombardment by meteorites, continental crusts began forming. Two hundred million years later, sedimentary rocks—compressed sediment layers—show the first evidence of life. Another billion years passed before the Earth’s internal convection mechanism began driving plate tectonics, shifting landmasses around the globe.

By the end of the Precambrian, Laurentia, the continent that became North America, was south of the equator abutting Antarctica and Australia. The landmass we now call New Mexico didn’t yet exist. We know where Laurentia was because when magma (molten rock within the Earth) cools, magnetic minerals in the cooling rock set as a permanent compass indicating where the rock was relative to Magnetic North and the equator. By aging the rock and comparing it with other rock formations, original locations and associations can be determined.

Between 1.6 and 1.8 billion years ago, two smaller continents consecutively crashed, albeit one millimeter at a time, into the southeastern edge of Laurentia. Too thick and light to go under Laurentia, these microcontinents accreted to the larger continent, creating most of New Mexico’s landmass. A few hundred million years later, a third microcontinent joined Laurentia, completing the state’s far southeastern corner. This created the state’s final land area, though not its final form. The primary components necessary for fossils to form and to be thrust into our view billions of years later had come together; Precambrian life and mobile continents were the beginning. The final component was ocean sediments that trapped the dead and dying lifeforms, mostly bacteria and single-celled animals, in layers on the sea floor. Weighted by new sediments and overlying ocean water, millions of years passed before compression rendered fossils—and likely millions more years passed before plate tectonics exposed those sediments to us.

The oldest rocks in New Mexico date back 1.75 billion years and are from the microcontinents that crashed into Laurentia. Although Precambrian rock underlies all continents, it is usually buried under newer sediments, including volcanic ash and lava. Few places in New Mexico have accessible Precambrian rocks. The western slope of the Sandia Mountains exposes 1.4-billion-year-old pink granite, often visible in the Rio Grande Valley evening light. The most notable thing about Precambrian rocks is that fossils in these strata are microscopic. The distinction between microscopic and visible-with-the-naked-eye fossils in the rock record divides Precambrian Earth from everything that came later. This is where Ancient Life begins.

The Cambrian: 541 to 485 million years ago or radiation, diversification, and increased complexity

A curious fact about the geologic record throughout much of North America is that Cambrian sandstone and limestone are not sequential with Precambrian rock. Typically, newer sediments provide a chronological record of environmental conditions, including fossils. Sediments are usually layered sequentially one on top of the next, with no breaks—rock layered like this is said to lay conformably on older sediment; this is called conformity. But in the Great Unconformity between the last Precambrian and the first Cambrian rock, there is a 1.1-billion-year gap in the global geologic record—these Precambrian and Cambrian rocks rest unconformably. A lot of questions surround this geologic saga because the Great Unconformity is, in places, thousands of feet below ground. Additionally, the timelines of when the rock disappeared in different locations don’t entirely match. In New Mexico, the Great Unconformity is visible in the Hatchet Mountains of the bootheel and the Sandia Mountains. These two mountain ranges also show the varied timeline. In the Hatchets, Cambrian Bliss Formation sandstone overlies Precambrian rock, and in the Sandias, it’s Pennsylvanian sandstone that sits atop the Precambrian granite—the time difference is almost the span of the Ancient Life exhibition. Whether completely eroded or never deposited, the geologic record for a significant portion of the Cambrian in New Mexico and elsewhere does not exist.

Primarily barren rock, Laurentia was far to the south during the Cambrian and at a 90 degree angle from North America’s current position. Modern-day New Mexico was at the southern end of higher-elevation land stretching from New Mexico to the Great Lakes. Sea level rose consistently during the Cambrian, and by the end, North America was bathed in warm, shallow seas and New Mexico’s higher elevations were islands.

There was no life on land yet, but at the beginning of the Cambrian multicellular sea life went rampant. Remember that missing billion years of rock? It’s thought the Cambrian proliferation of life was related to the erosion of that rock; as increased sediments, minerals, and nutrients became available in the global oceans, they nourished new lifeforms. This sudden radiation (expanding range), diversification, and increasing complexity of life is called the Cambrian Explosion. Most modern species are descendants of life forms that evolved then, including chordates—the first evolutionary step to vertebrates leading to humans. Another significant development was calcium carbonate shells and rudimentary skeletons, which allowed species to support larger bodies and defensive structures. These shells and armored plates may also have resulted from the missing rock, since calcium eroded from that rock likely saturated the oceans and was available for animals to use in shell building. Readily preserved, these structures provide an excellent fossil record.

Southern New Mexico mountain ranges hold the state’s Cambrian fossils. We commonly think of fossils as dinosaur bones and petrified wood; called body fossils, these are found in many museums and galleries. However, trace fossils, like fingerprints at a crime scene, provide evidence of animal behavior. Burrows, footprints, and scat—called coprolites—are trace fossils.

Although uncommonly found in New Mexico, Cambrian body and trace fossils, including trilobites, colonial animals called graptolites, and burrows, are exhibited in Ancient Life. Bottom-feeding scavengers and predators, trilobites were arthropods (relatives of modern insects, crustaceans, and spiders). Thousands of trilobite species are known, from flea-sized to two feet long; all have three lobes running the length of their bodies from head to tail. Broadly, they look like a cross between a horseshoe crab, with a helmet-like head, and a millipede, with narrow ridges crossing their bodies and numerous feet beneath.

What’s intriguing about the rock record is that no Cambrian species appear in the following period. Whether those species evolved into something new or were superseded by different species—a new top predator, for example—no Cambrian species are found in the Ordovician.

The Ordovician: 485 to 444 million years ago

or two rock groups, an unconformity, and a mass extinction

The earliest Ordovician rock is part of the Late Cambrian Bliss sandstone. The first wholly Ordovician rock is the El Paso rock group, which formed when much of New Mexico was still under warm, shallow seas south of the equator. Sea level fell and rose again, and thirty million years later, the Montoya rock group, which rests unconformably on the El Paso group, was deposited in cooler, deeper oceans. In New Mexico, limestone cliffs from Ordovician sediments are visible in the Big Hatchet and Florida Mountains, Oliver Lee State Park, and on Cookes Peak.

Primarily limestone and dolomites (limestone rich in the mineral magnesium), the El Paso and Montoya groups have poor fossil records because fossils degrade during the geologic formation of dolomite. These New Mexico formations collectively hold about four hundred fossil species. Yet, there are no fossil species in common between the El Paso and Montoya rock—no species and few genera. Every living species disappeared between the early and late Ordovician.

Globally, the Ordovician land was barren, but fungi and arthropods moved landward. In the oceans, animals without backbones, called invertebrates, like eurypterids (water scorpions), sponges, horseshoe crabs, crustaceans, trilobites, and nautiloids, were common. Nautiloids are cephalopods, relatives of ammonites (which appear later in the exhibition), modern squid, and octopuses. In Ordovician oceans, nautiloids, specifically the nautilus, were dominant predators. Vertebrates were rare, but jawless fish began diversifying. In Ancient Life, shelled animals provide the most elaborate Ordovician fossil record. Related to modern sea stars and sea urchins, animals called crinoids, or sea lilies, adhered to the sea floor with long stalks, and used tentacles to filter food from the currents. In New Mexico, pieces of fossilized crinoid stalks are found, but rarely the whole creature. Brachiopods first appeared in the Cambrian; superficially, they look like clams, but a single brachiopod shell divided in half is symmetrical side to side, whereas in clams, the front and back shells are alike. Some fossil brachiopod species measure fifteen inches across; the largest shell found in New Mexico is about four and a half inches long and is on display in Ancient Life.

By the late Ordovician, Gondwanaland, the supercontinent that held South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia, and India, stretched from the South Pole to the equator. Moving farther south plunged the globe into an ice age, and reduced sea level. The cooler climate and constricted oceans caused the first recorded mass extinction, which ravaged marine animals globally, setting the evolutionary stage back to mostly bacteria and invertebrates. Rapid reproduction, like that of bacteria especially, introduces more mutations and increases the chance of a genetic combination that will survive. With each successive generation building on mutations and adaptations of the previous generation, evolution happens rapidly—geologically speaking—and niches left by extinct creatures are quickly filled.

The Silurian: 444 to 419 million years ago or a post-extinction intermezzo

Once again under a warm, shallow sea and still on the southwest edge of Laurentia, New Mexico was south of the equator during the Silurian, and because Laurentia was still rotated relative to its current position, the equator ran from Quebec to California. After the Ordovician cold and extinction, surviving animal groups thrived in mild Silurian seas.

Brachiopods, corals, and crinoids increased in abundance and diversity, while trilobites began tapering toward extinction. Moving into brackish water, eurypterids were fierce, eight-foot predators. Jawless fish became armored, while the first fish and mollusks adapted to fresh water. Fish evolved jaws, and well-developed fins improved swimming. Top predators included cartilaginous fish like sharks and armored placoderms—fish with plated armor on their heads and necks. Meanwhile, terrestrial life was burgeoning. Drawing water from roots into aboveground stems, the first vascular plants formed the early terrestrial food chain. Soon millipedes and arthropods foraged in leaf litter.

Unconformities before and after Silurian dolomite provide a limited fossil record. Among corals, brachiopods, and bryozoans—an invertebrate also called sea fans—approximately fifty species were recorded, but degraded fossils provide tentative identities. Like earlier strata, Silurian rocks are found in southern New Mexico mountains (Big Hatchet and Florida), Oliver Lee State Park, and the Sacramento Mountain foothills.

The Devonian: 419 to 359 million years ago or the Age of Fishes and double decimation

In the early Devonian, landmasses that became eastern North America and Europe bumped into Laurentia creating the supercontinent Euramerica. Three layers of Devonian rock formed, each with a few million years’ gap and only a few common fossil species.

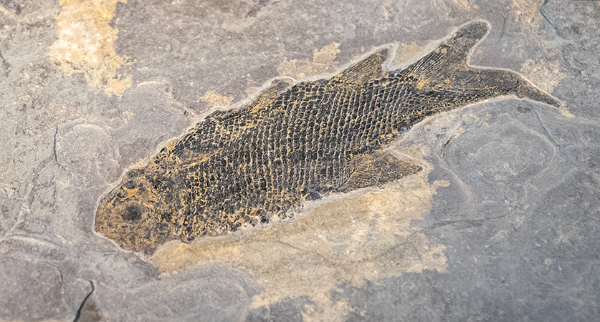

Ray-finned fish with webbed fins, lobe-finned fish with fleshy, muscular fins, and sharks and placoderms proliferated. Most living fish today evolved from prehistoric ray-finned fish. While their ray-finned friends stayed in the water, lobe-finned fish, like lungfish and coelacanths, colonized the land. By the late Devonian, these tetrapods, named for the four legs evolved from fins, adapted to life on land and the newly formed forests as trees, ferns, horsetails, and clubmosses flourished. Walking, breathing, seeing, and hearing on dry land are critical evolutionary innovations. All modern land vertebrates evolved from these early lobe-finned fish.

Devonian fossils include crinoids, brachiopods, and horn corals. Unlike corals today, horn corals were cone-shaped—the pointy end attached to the sea floor, and the animal filter fed from the wider opening. Ammonites, the octopus cousins mentioned earlier, became a dominant marine invertebrate and an important index fossil linking rock strata globally. Index fossils are important because they identify a narrow geologic timeframe across a broad geographic area, immediately tying one rock formation to another in time, regardless of location. Shark teeth fossils were the first evidence of fish found in New Mexico. While early sharks were barely three feet long, placoderms ruled the seas, reaching twenty-three feet, with armored heads and bodies and flexible tails. Placoderms eventually hunted oceans globally but became extinct by the end of the Devonian. A model placoderm skull from an animal called Dunkleosteus hangs in the Ancient Life exhibition. It includes a fossilized bone fragment discovered near Alamogordo—the only piece of this species found in New Mexico.

A hundred million years of ice ages began in the late Devonian, and in the final twenty million years of the period, two mass extinctions wiped out 70 percent of life. The prevailing theory on these extinctions is that glacial cooling triggered ocean water layers of different temperatures and oxygen content to flip. Deep, oxygen-poor water, heavy in organic material, lifted off the ocean bottom, spread across shallow continental shelves, and suffocated marine life.

The Mississippian: 359 to 323 million years ago or amniotic eggs and cockroaches

Life rebounded in the Mississippian, an interlude in the rolling, late Paleozoic ice ages when Laurentia was again under warm shallow seas. South of the equator, New Mexico was an island archipelago of lush rainforests and swamps. Bryozoans, brachiopods, and crinoids were dominant sea-bottom species, and ammonites hunted global oceans. Ray-finned fish and sharks diversified.

Foraminifera—single-celled organisms with calcium carbonate shells that are not classified as animal, plant, or fungi—exploded during the Mississippian, reaching nearly forty thousand species. Fossilized foraminifera shells form the Lake Valley Mississippian limestone found in southern New Mexico today. The tectonic uplift of Mississippian rocks caused significant erosion, leaving gaps between the Devonian and Pennsylvanian rocks, and many questions about life during this period. Serendipitously, within Lake Valley limestone, among more sought-after silver deposits, rich fossil beds were discovered. Plant and vertebrate fossils from this period are scarce, but crinoids, brachiopods, and bryozoans are the primary Mississippian fossils in Ancient Life. Bryozoans (sea fans) looked a bit like some modern corals and were colonial animals that lived on the sea floor.

Several amphibian groups evolved during the Mississippian, expanding into freshwater habitats and moist forests. Plants, insects, and arthropods expanded on land, providing new habitat for tetrapods. To date, amphibians were entirely dependent on water for reproduction, but amniotic eggs evolved by the end of the period. Enclosed in a hard shell, surrounded by fluid, and feeding from a nutrient sac, embryos developed in a protected environment without external water. While amphibians remained tied to wetter habitats, tetrapods diversified away from their relatives as a group of land-dwelling, egg-laying proto reptiles. As if amniotic eggs weren’t enough, cockroaches made their fossil debut.

By the late Mississippian, Gondwanaland and Euramerica united to form Pangea, and another ice age spread across the continent’s southern reaches.

The Pennsylvanian: 323 to 299 million years ago or the fossil hotbed

While cold gripped much of Pangea, New Mexico remained an archipelago near the equator. As isolated landmasses, these islands held upland forests and rivers that fed sediment to coastal plains. The sediments recorded variable sea level caused by fluctuating southern ice sheets. The Pennsylvanian Sandia Formation rock holds an almost complete fossil record, with 1,400 species and trace fossils like raindrops and river-bottom ripples. The Sandia sandstone surpasses all previous geological formations and represents marine, non-marine, and deltaic fossils, many of which can be seen in Ancient Life.

Forests weren’t as extensive during the Pennsylvanian, but conifers—trees with cones and seeds—evolved in drier highlands. Tetrapods began eating plants, and insects began flying. Amphibians and reptiles filled habitat niches as emerging plant communities and freshwater species spread. Plant photosynthesis and respiration increased atmospheric oxygen. With no land predators, giant insects evolved—some millipede-like bugs were eight feet long. A set of tracks in a trace fossil found near Abiquiu is the only evidence of giant arthropods in New Mexico. The bodies, as much as six feet in length, were discovered in Europe and Nova Scotia and described a long time ago. Until recently no one found a head to go with the body. Now, the tracks, the body, and the head with antennae and eyes on stalks will come together for the exhibition.

From the Manzano Mountains, a salamander-like species called Milnererpeton is so well preserved that its stomach and last meal of seed shrimp is identifiable. The most complete Pennsylvanian shark skeleton, Dracopristis, also came from the Manzanos. Sharks rarely fossilize because their body is structured around cartilage rather than a calcium skeleton. But this shark and the two-foot-long spines on its back—a highlight in the new exhibition—are spectacular. If a nine-foot shark needs two massive spines, presumably for defense, what was hunting it?

Lucas points to a fossil he and his colleagues found under a larger salamander skeleton. “This is something you’ll never see anywhere in the world except here. This is the oldest tree climbing reptile,” he says. “Its body would have been about that long,” he holds his hands about five inches apart, “Throw a tail on it. It’s like the size of a kitten” The only fossil of its kind ever recovered, it was found in Cañon del Cobre near Abiquiu.

The fossil, scientifically described by Lucas and named Eoscansor, has long fingers and toes and sharp claws that facilitated climbing. “When you think about it, this is a huge innovation, you know, to be able to climb trees,” Lucas continues. “It’s not easy, it’s dangerous, and you get this animal doing it at about 310 million [years ago]. And that’s the oldest record.” Imagine the risk of this adaptation—hunting in trees, moving over vertical surfaces against gravity, and the potential for a fatal fall.

By the late Pennsylvanian, Carboniferous rainforests were collapsing under ongoing glaciation. Although bacteria and fungi were living on land by this time, none were able to break down the woody plant material, and coal reserves were laid down worldwide. Becoming increasingly drier through the Pennsylvanian, New Mexico no longer had lush vegetation, and although graced with abundant fossils, it produced little coal.

The Permian: 299 to 252 million years ago or salt, reefs, and the Great Dying

At the beginning of the Permian period, Siberia joined Pangea to complete the supercontinent that spanned from North Pole to South Pole. New Mexico was north of the equator. The continent’s interior became desert, yet rock and fossil records show Pangea experienced monsoons like the seasonal wet and dry cycles of modern New Mexico.

Mostly above sea level, rivers drained to a tropical sea in the Delaware Basin, New Mexico’s southeastern corner. As the climate dried, floodplains turned to dunes and hyper-saline seas. Evaporation accelerated, leaving thick deposits of gypsum (calcium sulfate) and halite (rock salt). Few creatures lived in these salt-intense environments, and there are few fossils from this period, but flooding and evaporation cycles left salt deposits three thousand feet thick.

“At the end of the Permian, the Permian Basin dried out. It turned into what we call an evaporitic basin, and it left gypsum and salt, real salt, like halite, rock salt,” Lucas explains. “In New Mexico, they’re the youngest Permian rocks we have, and they show [the] evaporation of this great, famous Permian seaway that existed before.” Today, east of Carlsbad and 2,150 feet below southeastern New Mexico’s surface, this salt stratum encases a nuclear waste repository. Considered a safe medium for holding nuclear waste, salt under pressure is essentially a slow-moving liquid (it exhibits plasticity and deforms). As the salt changes shape, called salt creep, it engulfs whatever is in its path and, in theory, will seal the deposited waste and the mine. Along with pieces of layered gypsum from the Carlsbad area, a block of salt drilled from the waste site is on display. The salt, Lucas says, is “quite attractive because it’s got this, this kind of reddish mineral, probably it’s [an] iron oxide impurity. That makes it not just a big block of white rock.”

By the mid-Permian, the Delaware Basin flooded again, decreasing the water salinity. This shallow sea held many earlier Paleozoic species—or their evolved descendants, and calcareous sponges and algae built a reef encircling the basin. When the ocean retreated, the reef died and was buried in sediment. Millions of years later, tectonic activity exposed what is now Carlsbad Caverns and the Guadalupe Mountains, the world’s largest, best preserved, and most studied Paleozoic reef.

Elsewhere, tetrapods continued radiating, and coal-forming forests dwindled in the arid environment. Surrounding deserts with freshwater oases were rife with trace fossils, plant impressions, and body casts. In the seas, marine animals and driftwood fossilized. A trackway from the southern New Mexico beaches, Celeskey says, is “pretty close to [a] Gordodon fossil… [with] spines and the skull that was collected near Alamogordo. You can estimate the length of the animal, from the distance between the steps.” Lucas continues, “In the early Permian, say, 280–290 [million years ago], that’s about as big as footprints get. That’s one of the bigger footprints you’d ever see. It’s about the size of your hand.”

The current scientific theory is that massive eruptions in the Siberian volcanic fields initiated radical climate change, increased ocean acidity, and an altered carbon cycle. In the resulting mass extinction during the Permian, called the Great Dying, 95 percent of life was extinguished—the largest mass extinction in Earth’s history. Although the dominant life form then and now—bacteria—returned to business as usual, the rock record was nearly reset to microscopic life. The lifeforms that survived tended toward groups with numerous diverse species, some of which may have already adapted to similar conditions—bacteria at deep-sea hydrothermal vents, for example, and those groups with more generalist species that could readily move into niches left by newly-extinct creatures. The remaining life continued evolving, finally appearing as and with dinosaurs in the Age of Reptiles.

The scale of time covered in Ancient Life and this article is rivaled only by the scale of effort required by museum staff to turn this vast story into something accessible to everyone. The struggle is not to find enough fossils because New Mexico is bountiful in these; the difficulty lies in bringing a comprehensive view of this era to life for visitors who range in age from eight to eighty. The three thousand square foot exhibition includes fossils, of course, but also maps, murals, artwork, sculptures, and reconstructions. While most Ancient Life material came out of the New Mexico rocks, everything that completes the exhibition, including the fabrication of individual specimen mounts, came from the research and creativity of people behind the scenes. When they do their jobs well, staff members remain unseen but deserve credit and praise for creating this world for us.

The closing scene of Ancient Life requires walking through a reconstruction of an arch in the Guadalupe Mountain reef. Many millions of years have yet to pass before the New Mexico we know takes shape. Stepping through the reef into the Great Dying and on to the realm of dinosaurs featured in other exhibitions, visitors can consider all that occurred in the Paleozoic, and what lies ahead. The next mass extinction took the non-avian dinosaurs and opened the door for the diversity of mammals, including humans. Ancient Life shows us that Earth, its climate, and lifeforms are constantly changing over geologic time. Today’s rapid, human-driven changes reflect the global conditions that caused the late Permian extinctions. If we continue this way, how does our story play out? What is the rock record we are leaving behind, and who will be here in a few million years to read that tale?

–

Tamara Enz is a writer, photographer, and biologist who spent thirty years studying birds, plants, and natural habitats. She is the author of two bird guides and is now writing (un)frozen, creative nonfiction about living alone on an Arctic Ocean island.