A Parallel Beauty

Finding Home in Santa Fe

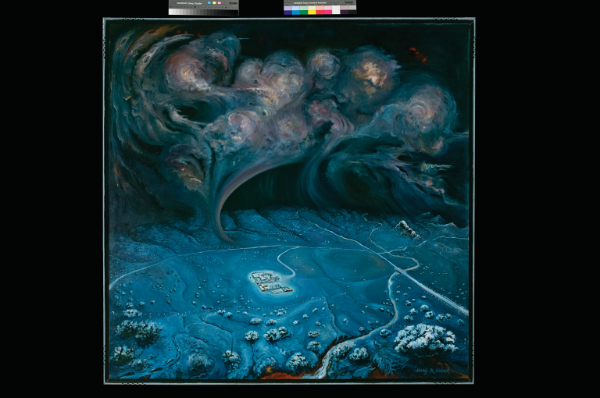

Jerry R. West, Prairie Homestead with Approaching Cosmic Storm, 1989, oil on canvas, 71 × 75 in. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of Ray Graham, 1991 (1991.54.1). © Jerry R. West. Photo by Blair Clark.

Jerry R. West, Prairie Homestead with Approaching Cosmic Storm, 1989, oil on canvas, 71 × 75 in. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of Ray Graham, 1991 (1991.54.1). © Jerry R. West. Photo by Blair Clark.

By Pam Houston

I was on a video call early in the pandemic with my friend Jamie Figuroa, when I articulated it for the first time. I had just finished reading her novel, Brother, Sister, Mother, Explorer, which is set in Santa Fe and captures so well the community’s beauty and power, as well as its dangerous magic and its shadowy underbelly. There are a group of older women who pedal along the edges of scenes on bicycles. They are protectors, working against sex traffickers and other vestiges of the patriarchy, collectively called “the grandmothers of us all.” I told Jamie that reading her novel made me know in my bones Santa Fe was my ultimate destination, that I had been in as deep and complex a relationship with Santa Fe for the last thirty years as I had with any other person or place in my life. Because Jamie is wise enough to understand both that I wanted to be a grandmother of us all, and to be tended by them, she said, “Santa Fe feels the same way about you, Pam, and I think it is time you came home.”

I have not come home to Santa Fe quite yet, for a number of reasons, including a couple of aging horses who like the one hundred and twenty acres they move about at my actual home two hundred miles up the Rio Grande from Santa Fe outside Creede, Colorado. There are the three Icelandic sheep in my dwindling herd, the four chickens who survived the avian flu that swept in with the wild birds last winter, and the dogs who are not schooled in leashes or fences or dog parks. There is the barn, the only non-living object I cared about saving when evacuation threatened during the 2013 West Fork Fire, and the thirty-five years of memories I have made living there. Also, even if it were easy to sell my Colorado homestead, which it will not be, sitting as it does at the end of a long dirt road in a place that is serious about winter, I could not trade across for even the smallest home in Santa Fe, at least not an intact one, and sixty-two might be too old to take on another mortgage.

Are we doomed to love our spiritual homes more than our actual ones? Does Santa Fe retain its perfection in my eyes because animal logistics and gentrification will make it nearly impossible for me to live there? Is she like the secret lover who never ages or becomes tiresome by virtue of never being captured? Am I like the guy who agrees to go steady with the girl only after he finds out she has six months to live?

My first visit to Santa Fe occurred around the same time I bought my place in Creede, in the late fall of 1992, not long after the publication of my first book, Cowboys Are My Weakness, when I was a guest of the Santa Fe Writers Conference. After giving my reading, I was taken out to Galisteo to the home of ceramicist Vicki Snyder and her writer husband David, for a dinner with other artists on their portal. Theirs was the coolest home I had seen at the time, lit up with luminarias, the real adobe walls adorned with ristras and milagros. I thought “this is what it must mean to be a grown up, to have created a home that feels like a heart.” I had just turned thirty and had spent much of the previous decade sleeping in my North Face VE 24 tent, or my Toyota Corolla, or a shack in Park City, Utah, which I could afford on my graduate school budget. Not that the Galisteo house was grand. It was not grand, and that was the beauty of it. It was perfect. Warm, compact, elegant, of the earth. As I sat there, I could still feel the hands shaping the walls.

Santa Fe is four hours from my Colorado homestead, door to door. It’s my closest art house movie theater, my closest sushi, my closest real latte, my closest grocery store that carries quality olive oil and Malden salt. Each time I made the trip, I met another Santa Fean who engaged with, cared about, and configured their lives around art. I had not known it was possible to design a life that way. In Colorado, I had chosen wilderness, my lucky horseshoe of mountains, a million acres of aspen trees beyond the property line to get lost in, a sky where the Milky Way remains as its name suggests. What Santa Fe offered was a community of people who wished to investigate a parallel beauty, beauty made by human beings.

At first, I was bedazzled by the Plaza, lit up by a thousand holiday lights, or packed full of Zydeco dancers at a free summer concert. I fell for the hole-in-the-wall that was Holy Spirit Espresso, a walk with my dogs on the Chamisa Trail loop in October, and a soak in the women’s pool at Ten Thousand Waves. Eventually I discovered the Santa Fe that thrives on the other side of Saint Francis: Counter Culture, Mu Du Noodles, and eventually Tune-Up, with its whole world of flavors. The people I met were using their talents to fight for climate and social justice. This corresponded perfectly to my political awakening, my growing understanding of the inequities and supremacies that direct this country’s policies, and our collective denial about our many crimes.

I met a poet in Santa Fe who lived in a tiny apartment in a compound off Acequia Madre. When I visited him, I walked Canyon Road daily, marveled at the sheer density of galleries, and eyeballed Cormac McCarthy from behind my laptop at Collected Works. The poet had an ex he was still entwined with, and I don’t want to dwell on that trouble except to say that it was the first real challenge of my relationship with Santa Fe. I fell out of love with the city for the first and only time. I think of what followed as a trial separation from Santa Fe; we took a little break from each other. Eventually though, the poet moved to California, and Santa Fe and I rekindled our relationship, shyly at first, and then with reinvigorated passion. We renewed our vows as our friends looked on.

Then, one snowy Saturday in January, something happened that solidified my relationship with Santa Fe so completely no poet will ever tear it asunder. I was home alone, happy in the middle of a three-day blizzard, when the phone rang. It was the then-director of the newly minted MFA program at the Institute of American Indian Arts, Jon Davis, asking how soon I could be in Santa Fe. Mona Susan Power, who was scheduled to read that night, couldn’t make it, and he was looking for a replacement who was not afraid to travel in the snow. I stepped outside and looked at the fat flakes falling from the sky, eyeballed my moderately drifted driveway, looked toward the horses munching peacefully on the hay I had thrown an hour before.

“I would have to bring my dogs,” I said. “I don’t have a sitter.”

Jon said, “I’ll get you a dog-friendly hotel room.”

I said, “Make sure they like big dogs, together my two weigh three hundred pounds.”

I arrived at IAIA unbrushed, brushless, and covered in dog hair, but on time for the reading, and with a promise from my neighbor to throw hay for the horses early the next day. I dashed to the women’s restroom to try to address my hair and perhaps shed some of the dogs’. I asked the first three women who came in if I could borrow a hairbrush. To a person, they smiled, friendly and apologetic. “Sorry, I don’t have a brush, I just kind of run my hands through my hair”—here she demonstrated—”in the shower and call that good.” Another said, “No, I gave up hairbrushes the same year as underwire bras.” These were decisions I could relate to. I liked IAIA already.

The morning after my reading I sat at a table of mostly Diné writers, including Byron Aspaas, and though I cannot remember the subject, I do remember laughing so long and hard it was impossible to eat. Byron wasn’t the only friend I made at IAIA that day, but he was the one to stand beside me as my best man four years later when I got married. Before I drove away, Jon asked if I would consider returning, and I haven’t missed a semester of teaching in that program since.

In the Low-Rez program we meet three times a year for eight days at a time, so while my job there has not massively increased the number of days I spend in Santa Fe, it has increased the range and quality of my interactions. My colleagues and students belong to many different Nations, but we come together in Santa Fe as a community, to learn, laugh, cry, argue, listen, read, and write. We go on excursions to IAIA’s Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, Tune-Up, Meow Wolf, and sing karaoke. Because of when our residencies fall, I have celebrated my last twelve birthdays with them. The amount I have learned from being in proximity to their varied but consistently Earth-centric, community-forward, empiricism-challenging values has changed me—as it would anyone. It has been quite simply the most valuable education of my life.

In my first full year teaching at IAIA, I mentored Dia Winograd, who is non-Native and has been a resident of Santa Fe for forty years, and Northern New Mexico for even longer. Over the last decade she has become my chosen mom, because she’s a yes-sayer, hilarious, makes the best gluten-free meatloaf on the planet, and because she is sober. My mother, who was not sober, died when I was thirty. I didn’t know how exhausted I was from a quarter century of motherlessness until Dia came along. Dia lives in Eldorado, behind a lilac bush that’s as big as my barn. Because I have no clothes drier at home, I bring my laundry to Mama Dia’s, which makes us both happy. We walk the Eldorado trails for hours and when the weather is too shitty for walking, we dance to ’80s music in her living room.

I got COVID-19 in February 2020 and was sicker than I had ever been. Lungs, sure, but also heart palpitations and joint aches, kidney failure, and nose bleeds that lasted weeks. No Western doctor wanted anything to do with me. We had not even begun saying the words Long COVID yet, so I begged Alix Bjorklund, a Sante Fe acupuncturist who had been recommended to me over the decades but was never taking new clients, to have mercy on me, and she did.

Cynthia Baughman, longtime Santa Fe resident and former editor of El Palacio, traded me the condo her mother left her for membership in my private writing group since all short-term rentals had been temporarily disallowed. This gift allowed me to see Alix three times a week when I was so sick I could hardly function. Being two thousand feet lower in elevation than Creede gave my lungs a fighting chance. Cynthia’s condo is downtown, catty-corner from the big metal dog who wears the bright red Christmas collar. Sometimes Pasqual’s was open and sometimes La Boca, and Iconik was always open, so I managed to keep myself fed. It was a lonely time but somehow the empty streets I walked kept me company. On the way from the condo to Iconik on Guadalupe each morning, I would pass the elephant that sits on the swing painted on a wall near the Chile Line Brewery and greet him as if we were friends. Somehow the happiness conveyed in the back muscles of that elephant made me believe things might one day be okay.

One night, when I’d had way too much of my own company, I double masked and stopped into a sock shop near the Plaza. The woman who worked there recognized me—a thing that happens to me sometimes in Santa Fe and nowhere else on Earth—and she said, “Pam, do you think the fascists will come all the way to Santa Fe to get us, or do you think we will be safe here?”

“I think the fascists will leave Santa Fe alone,” I said, without a ton of confidence, “but if they don’t, I think this community will stand up and fight on behalf of one another.”

Was this the sort of fantasy a person who is pretending to live in their favorite town engages in? If I actually lived in Santa Fe, would I believe it would be every person for themselves?

A few nights later I was walking back from Pasqual’s with my garden burrito and my vanilla date shake (one of the best meals in any time) and I rounded a corner to see a lone man on the otherwise deserted sidewalk. As was the protocol, I stepped into the empty street, and he did too. He laughed and said, “No, you have food, you take the sidewalk.” I had been right then, I hoped, to say Santa Feans would fight for each other.

In the spring of 2021, my strength increasing, I took what I called “the long walk” daily: up Marcy Street, across Paseo, up Hillside to Rodriguez, Rodriquez down to Palace, Palace to Canyon, then Monte Sol over to Acequia Madre, down to Garcia, over to Cathedral, and back downtown. It took an hour and fifteen minutes if I didn’t have to stop and rest. In May, a century plant bloomed on the corner of Palace and La Vereda, and I took pictures of it every day to mark the passage of time.

Eventually COVID restrictions came to an end, and the condo became a short-term rental again. I rented a house briefly in Chupadero, and when that rental ended abruptly, one of Dia’s two spare bedrooms became mine. My life revved up too. I was teaching in California, France, and Wisconsin, and my lungs got strong enough for me to spend time back in Creede. But Santa Fe had solidified itself in my heart and soul as the place that had healed me. Through sickness and health, we had promised one another, and Santa Fe had delivered big time.

In late November 2024, after the presidential election, I noticed Santa Feans had switched back into COVID mode, which is to say, they were being particularly tender with one another. At Iconik one morning, three different strangers told me they liked my sweater, and while it is a truly great sweater, hand knitted for me by a friend, I knew it was less about the sweater and more about saying, hey, you are a person and I am a person and we are both hurting and I see that you are here.

Is home the place you bring your laundry? Or the place you learned you had a political self? Is it the place you weathered a physical or emotional storm? Is it the place you found the mother you always wanted? The place you see your values reflected in the eyes of others? The place where you believe strangers will stand up and fight on one another’s behalf?

It remains to be seen if I will I ever commit wholly to Santa Fe, get right down in the trenches of old age with her, or if she will remain my other woman, the name I’ll call out with regret on my death bed. For now, just out of frame, the grandmothers of us all are beckoning from their bicycles, saying something wise like it is a very lucky woman who can claim to love more than one home.

—

Pam Houston is the author of the short story collection Cowboys Are My Weakness, the memoir Deep Creek: Finding Hope in The High Country, and six other books of fiction and nonfiction. She teaches creative writing at The Institute of American Indian Arts and UC Davis, is cofounder and creative director of the literary nonprofit Writing By Writers, and fiction editor at the environmental arts journal Terrain.org. She lives on a homestead at 9,000 feet near the headwaters of the Rio Grande. Her book, Without Exception: Reclaiming Abortion, Personhood and Freedom, was published by Torrey House Press in September 2024.

Art and Belonging

A few months ago, I met Pam Houston at the New Mexico Museum of Art’s Vladem Contemporary, and we walked through Off-Center: New Mexico Art, 1970-2000 together. The exhibition opened last summer and rotated through the themes of place, spectacle, and identity. As we drifted from one work to another, Pam and I talked about place, belonging, experiences in New Mexico, and what makes a place a home. Our conversation was as varied and wide-ranging as the breadth of work represented in Off-Center. The images that appear alongside her essay are ones she was especially drawn to at the exhibition.

Off-Center, which closes on May 18, 2025, runs through a survey of the last three decades of the twentieth century, a pivotal time in which numerous artists relocated to New Mexico, drawn by its distinctive climate and landscape, its rich diversity of cultures, and its strong reputation as a center for the visual arts. Between 1970 and 2000, Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and Taos continued to be important destinations for contemporary artists, but other communities developed in cities and towns infrequently identified with the visual arts such as Galisteo, Gallup, Las Cruces, Roswell, and Silver City. With over 125 artists on view, Off-Center presents a compelling range of artistic approaches and a diverse range of experiences. —Emily Withnall