Weaving New Meanings

Telephone Wire Basketry in Context

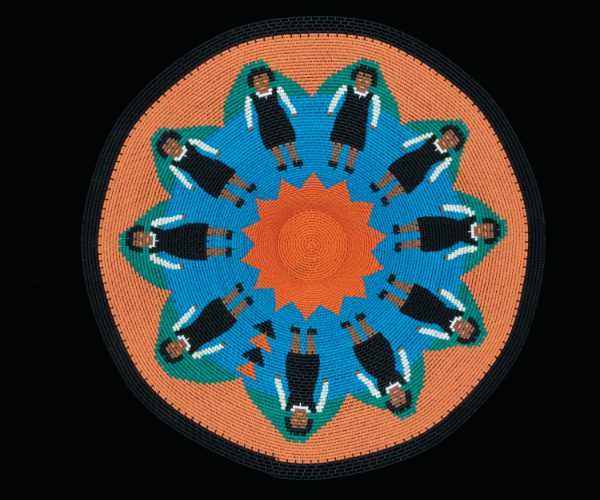

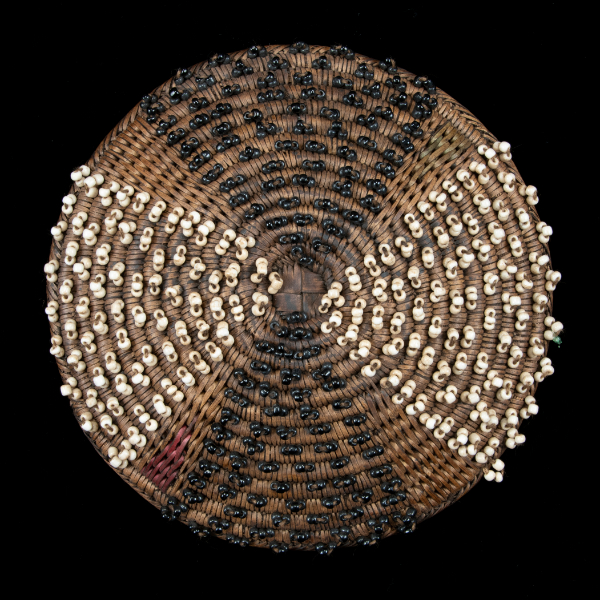

Zodwa Maphumulo. School Children, 2003. Telephone wire, wire.

Siyanda, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Gift of David Arment and Jim Rimelspach, David Arment Southern African Collection, IFAF Collection,

Museum of International Folk Art, FA.2024.12.241.

Zodwa Maphumulo. School Children, 2003. Telephone wire, wire.

Siyanda, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Gift of David Arment and Jim Rimelspach, David Arment Southern African Collection, IFAF Collection,

Museum of International Folk Art, FA.2024.12.241.

By Elizabeth Perrill, with Muziwandile Gigaba and Lillia McEnaney

Without traffic, it only takes thirty minutes to reach KwaMashu and Siyanda. Past Durban’s inner suburbs, stadiums, mansions, and malls, I reach the few highway entrances that connect these historically Black neighborhoods—home to over 175,000 people, over ninety percent of whom are isiZulu-speaking—to the rest of this 3.25-million-person harbor city. As I enter KwaMashu, the road narrows and the terrain becomes less grid-like. Roads loop across the hillsides where Durban’s migrant-labor population has lived since the 1960s, when the government controlled Black labor and determined who was officially allowed to live in this city-beside-a-city.

Today, tucked between the official Township of KwaMashu and the highway is Siyanda, a majority isiZulu-speaking community that was never planned or condoned on official maps. The informal settlement boom town was first built from corrugated iron and whatever materials were at hand. Now, cinderblocks and more traditional building materials have replaced the insecure housing materials of the past. These two neighborhoods, KwaMashu and Siyanda, are the incubators of telephone wire art, a distinctly South African art form.iNgqikithi yokuPhica/Weaving Meanings: Telephone Wire Art from South Africa is the first major exhibition of South African telephone wire art in a North American museum. It opened November 17, 2024 at the Museum of International Folk Art (MOIFA) in Santa Fe.

“The title iNgqikithi yokuPhica is a poetic expression that encourages us to grapple with the meaning of art,” says Muziwandile Gigaba, community curator and lead Indigenous knowledge expert based in KwaMashu Township, Durban, South Africa. “iNgqikithi means an essence or deep foundation. Ukuphica (the root verb of the title’s yokuPhica) usually refers to a weaving technique but also may refer to a riddle. Riddles may seem confusing at first, but they have a clever answer or unexpected meaning in the end.”

A celebration of the tenacity of South Africans, this exhibition is built around the David Arment Southern African Collection, key loans, and documentary footage filmed and edited by a South African production team, Zamo Mkhize’s Gone Fishing Productions. Interview footage featured in five short documentaries foreground the voices of artists, historians, and community members who witnessed the emergence and development of this art form from the mid-twentieth century onward.

One of the first artists visitors encounter in the series of documentaries that fill the galleries is Zodwa Maphumulo, the matriarch of the Maphumulo family. While looking at her work and the work of her family members, the viewer won’t know that on July 13, 2023, as Maphumulo was settling in for her interview, lights set, boom mic in place, and sound levels checked—the power went out. It wasn’t only Maphumulo who lost power, it was all of Siyanda and much of neighboring KwaMashu. Annoyed but unfazed, our entire team, including Gigaba, the Gone Fishing Production team, and I, as well as the entire Maphumulo family, pulled out our phones to check the “ESP-Loadshedding” app. The app allows residents to see when power outages will occur in their neighborhoods, and when an unexpected outage hits it gives an estimated time for the power to return.

That’s just daily life in South Africa because of unstable infrastructure and cities that were designed for a minority of South Africans. White elite areas, surrounded by pools of government-controlled enclaves of people of color, were designed under Apartheid. When freedom of movement was finally permitted in the 1990s, the infrastructure was taxed by a flood of urban immigration. Today, scheduled rolling power outages called “loadshedding” take place regularly to avoid nationwide blackouts because the entire power grid is under constant stress.

Though the outage wasn’t on the schedule, our team made a strategic move: We shifted to an outdoor interview with Ntombifuthi (Magwaza) Sibiya, a nearby weaver of the same generation living in Siyanda. Like the telephone wire weavers who are used to improvisation and resilience, this team of township-raised professionals knew the backup generators and batteries would likely last until the power came back on. They work in South Africa’s booming film industry and know what local conditions demand.

Origins in Resistance and Racism

The Apartheid South African government’s policy of racial segregation existed from 1948 until 1994 and was the oppressive system from which telephone wire basketry emerged. In this era, white cities and farms were separate from Black, Coloured (a mixed-race category defined by the Apartheid government), and Asian populations. Neighborhoods were segregated, and industries relied on Black migrant workers based in rural areas and those living in government-controlled Black townships for labor. Experimental pieces of wire embellishment on sticks and izimbenge (beer pot lids) emerged in rural and urban spaces soon after telephone lines were laid in the mid-twentieth century.

Unfortunately, early trade in these experimental pieces was often driven by a desire for artworks by Zulu artists that satisfied a generalized category or type, but that was not attributed accurately to an artist—much akin to the collecting worldwide of Indigenous peoples’ arts during this period. Even when collectors sought out the names of artists, circuitous and extractionary exchange routes erased the identity of Black weavers from the rural, government-created “Homelands.” These Homelands were often not the weavers’ historical homes; the Apartheid government created Black Homelands through forced and traumatic displacement. And, unfortunately, artworks exported from the Black-designated KwaZulu “Homeland” to the white-controlled province of Natal were, most often, labeled only as “Zulu.”

Direct contact between individuals in different race categories, as designated by the Apartheid government, was strictly controlled. Mixing between races in a range of settings was illegal. But, even with the barriers set between racial groups under Apartheid, art did construct a space for some communication and mutual support. Liberal-leaning arts organizations, run largely by white South Africans and sponsored by a few international aid organizations, supported rural arts development and sales. Through white intermediaries—often nonprofit employees or volunteers who were in contact with Black-designated rural areas or townships—art was sold in white South African spaces and to buyers abroad. The African Art Centre, which opened in 1959, ran workshops that initially only engaged with art media known to be produced by isiZulu-speaking populations historically: weaving in natural fibers, carving, ceramics, or beadwork.

Artists started experimenting with coated telephone wire in the mid-twentieth century. Particularly during the 1980s, the telephone network in South Africa expanded. The individuals who first used wire experimentally on walking sticks or as small areas of color on natural fiber weaving were likely stripping colored wires from waste materials at building sites or along infrastructure construction sites. The exact origin point has not been established. Paul Mikula, an architect and collector of Zulu fiber weaving who founded the Phansi Museum in Durban, facilitated a waste-wire distribution site once the art form started to expand in the 1990s.

This bright and expressive material speaks to a range of Indigenous art forms in what is today KwaZulu-Natal province—the rich embellishment found in historical copper or brass weaving, fiber basketry-weaving techniques, and beadwork color theory. The African Art Centre first sold telephone wire embellished works in the 1980s, and later another nonprofit, the Bartel Arts Trust (BAT) Centre and the BAT Shop, opened in the 1990s, as well as a range of independent galleries supported the sales of telephone wire domestically and internationally. Once Apartheid officially ended in 1994, the diversification of sales points expanded.

In urban spaces, Black night watchmen, employed by white property owners, spent their evenings embellishing the only weapon they were allowed—traditional wooden clubs and sparring sticks. Some of the oldest embellished objects in the exhibition, wooden clubs, sparring sticks, and snuff horns covered in wire, tie wire weaving back to the value placed on metal rods and wire in early Southern African trade routes that have existed since at least the sixteenth century. In the nineteenth century, imported wire was used to wrap sparring sticks and small personal objects. The fine weaving of copper and brass wire on prized nineteenth-century sparring sticks and a rare snuff container—on loan for Weaving Meanings—inspired the earliest telephone wire weavers.

Celebrating Artists Shaping a Nation

Elliot Mkhize, a resident of KwaMashu, was a key figure in the expansion of the telephone wire art form in the 1980s and 1990s, just before South Africa’s emergence from Apartheid. Mkhize trained at the Ndaleni Art School in the 1960s, one of few art schools during Apartheid that trained Black artists. At Ndaleni, Indigenous art forms from KwaZulu-Natal, alongside Western-derived printmaking, painting, and sculpting were on the curriculum. After his formal education, Mkhize, the son and grandson of sculptors, gravitated to Durban’s city center. Mkize became a nightwatchman at the Playhouse Theater across from the city’s history museum and city hall, and near the African Art Centre and other galleries. Other night guards taught him to weave around telephone wire sticks. Mkhize realized that telephone wire might also be used to weave the palm-fiber patterns he had been taught at Ndaleni Art School. He quickly began making small izimbenge (beer pot covers) in bright telephone wire patterns. Mkhize explained in a 1997 conversation with artist and art historian Carol Boram-Hays, “The patterns will just come by themselves while I’m working […] like a dream.”

This narrative, woven by an expert artist and storyteller, claims to be the origin of telephone wire basketry. But evidence of earlier telephone wire basket weaving in the mid-twentieth century, seen in Weaving Meanings, attests to an earlier origin. What Mkhize and others agree upon, however, is that something shifted within the Durban art world at the end of Apartheid. A celebratory and unifying spirit was a part of the tense yet optimistic shift that occurred from 1990 to 1994 as Nelson Mandela, the African National Congress leader who had been imprisoned for twenty-seven years, and F.W. de Klerk, then the president of South Africa, sat down to negotiate a peace accord that led to South Africa’s first election in which all races could legally vote. This 1994 vote and the years after were a moment when telephone wire became a symbol of “The New South Africa.” This phrase—The New South Africa—was used repeatedly and conveyed the optimistic fervor of national and international onlookers alike that peace might prevail.

“Despite his passing in 2020, Elliot is still revered in his neighborhood as a living ancestor, and his presence is still felt,” says Gigaba. “Elliot carried isithunzi sokuhlakanipha (prestige of wisdom) throughout his career as a mentor and teacher. His geometric shapes are a nod to ancient Zulu hierographic writing, as if navigating the past to forge a new abstract language.”

Another artist featured in the exhibition, Dudu Cele, created telephone wire works that overtly communicated South Africa’s new branding. Her flag plate hangs in the gallery within a case of several pieces produced in the late 1990s and early 2000s that featured the new South African flag. During the optimistic moment following the peace accord, art centers and galleries in South Africa and abroad catered to a wide range of patriotic South Africans, to tourists who flooded into the newly open South Africa, and to international shops interested in celebrating the design and optimism of the country’s vibrant cultures. The art form of telephone wire flourished in the late 1990s and early 2000s and the love of design, pattern, and intricacy, which is such a driving force in Zulu beadwork and weaving, came to the fore. Artists like Ntombifuthi (Magwaza) Sibiya and her husband Bheki Sibiya, Vincent Sithole, and Simon Mavundla produced work that won a range of national design and craft prizes and that pushed the intricacy of design within the art form to new heights.

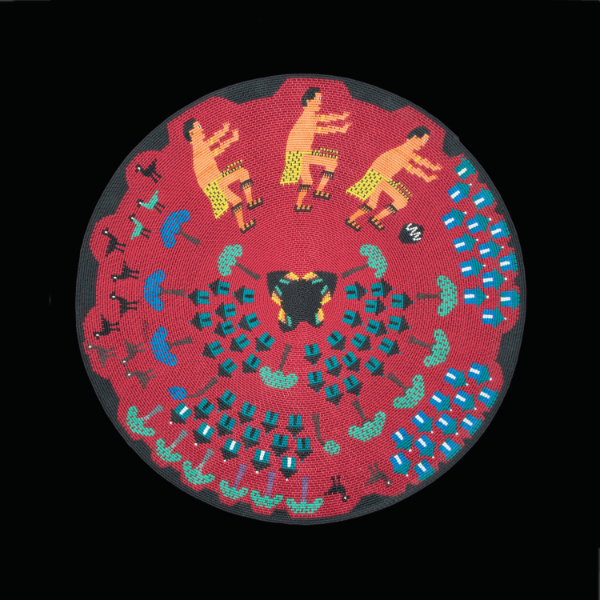

Today, the spirit of community-minded engagement and design innovation endures. New generations of artists have shifted their focus from patriotism to new concerns. Weaving Meanings honors this generational progression. One contemporary artist, Thembinkosi Maphumulo, creates work that reveals a deep concern for the natural world. In one piece, he depicts dung beetles—an indicator species that reflects the health or decline of an ecological zone. Dung beetles speak to both the health of the environment and the community. For Maphumulo, being ecologically minded and upholding traditional values and Zulu identity go hand-in-hand.

Pride in Language and Transforming Culture

The importance of language as a site of pride is clear in the telephone wire artworks from the 1990s, as South Africa emerged from Apartheid. Bheki Dlamini, one of the first generation of telephone wire weavers who was able to turn this art form into a full-time profession, created a basket with the words “Udwendwe Luka Koto” emblazed above a figurative scene. This title translates to “Koto’s Bridal Party,” and is just one of a range of baskets found in the galleries at MOIFA that use woven words to emphasize imagery.

Gigaba observes of the basket, “The composition here is inspired by a [radio] drama series that grappled with social issues and challenges and shifts in the South African socio-geographical landscape following the lifting of South Africa’s unjust land acts. With new mobility, different tensions emerged between Black people who had assimilated into urban spaces as migrant workers with those in rural communities. This inspired a change in lifestyle that ended up affecting cultural practices and traditions such as courtship.”

Dlamini was living in the heart of the neighborhoods featured in the radio drama Udwendwe Luka Koto. He and his peers were the immigrants who flooded in from rural areas to settle in the townships and informal settlements that surround Durban, and he clearly connected deeply with the content of this radio program. The drama engaged with the many cultural norms that were held in rural spaces. For instance, rural marriage was often an ongoing and multi-step process between two families, but when many Black South Africans from a range of backgrounds moved to urban spaces the marital negotiation process and other social norms changed. Udwendwe Luka Koto spoke to these changes and tensions that were growing between rural and urban, old and young. Dlamini reflected his love of this show, and with it the rich and complex realities of contemporary Zulu identity, in his weaving.

At the top of Dlamini’s basket we see light blue trapezoids, each with a yellow spot along its base. These peaked roofs represent thatched homes with entrances. This is a style that has been used by subsequent artists, but Dlamini’s original intent was not recorded during his lifetime. As with most of the first generation of artists, Dlamini passed away without conveying his full message. What is clear is that he depicted a ring of Zulu women, each holding a small spear and miniature shield associated with young women. They wear small headdresses, chest coverings, skirts, and leg bands that are instantly readable to a Zulu audience. Rows of concentric colors emphasize the joyful tone, and near the center, nine white ovoid shapes with eight symmetrical markings appear.

This piece helps us understand that the celebratory baskets of isiZulu-speaking artists, even when made for export, are layered in meaning. To those who know Zulu cultural symbols it is clear the ovoid shapes are shields. The base color of the shields is white, emphasizing the clarity and purity of the young women. It seems that Dlamini had a positive spin on the radio dramas heard in Udwendwe Luka Koto, as the ring of young women conveys both their pride and self-assurance.

The exhibition space for Weaving Meanings emulates a Zulu household’s layout. The isibaya cattle enclosure, a sacred circular space where generational ceremonies take place, forms the center of Zulu homestead. This space is where ancestors are consulted, surrounded by the houses of family members. Likewise, Weaving Meanings features key lineages in its central room. Zodwa Maphumulo, the matriarch of the family; Thembinkosi Maphumulo, her son; and Nobuhle, her granddaughter, are also featured in this central ancestral space.

Telephone wire basketry can be understood as a point of entry into thinking about South Africa’s complex histories, colonial politics, and diverse community contexts. Through a discussion of the creation of an entirely new artistic medium, visitors to Weaving Meanings will see artistic innovation emerge as a means of resistance, nation-building, and cultural pride.

Conclusion

Weaving Meanings rewards close looking. In addition to emphasizing Zulu and South African aesthetics, the exhibition focuses on the complex political, economic, and sociocultural contexts in which these baskets began their lives. Weaving Meanings asks visitors to think deeply and critically about what constitutes “meaning.” A meaning is not simply representative imagery—what we may think of as symbols or iconography—but instead asks visitors to think about meaning as culturally produced and constructed, made real through the actions of both individuals and communities. As artist Zodwa Maphumulo says, “Sometimes, I weave baskets seeking to archive history that would serve as a tangible reference for future generations.”

Thankfully, younger generations from the weaving families of Siyanda and the inheritors of the arts infrastructures of Durban’s city center are ensuring the legacies of telephone wire continue. Although telephone wire can no longer be readily salvaged now that cell phones have taken over the global infrastructure, families custom-order wire and continue this weaving tradition. Nobuhle Maphumulo, Zodwa’s granddaughter, works closely with her extended family. When large orders come in, the Maphumulos divide the work and share the profits. But each artist is also forging their own path. Twenty-eight-year-old Nobuhle browses the internet on her phone to bring in imagery and color combinations that shape her own style. She’s also an aspiring teacher.

From August 17 to 20 of this year, Nobuhle traveled daily into Durban from Siyanda to lead her first class in weaving telephone wire. The course, materials, and students were coordinated by Nozipho Zulu through her business, ZuluGal Retro. Nozipho is a young arts professional who graduated with an art degree from the Durban University of Technology and worked as a Manager at the African Art Centre, the same organization that sold Elliot Mkhize’s wire baskets in the 1970s. Nobuhle and Nozipho are just two examples of the younger generations in South Africa who are continuing the legacy of telephone wire, centering their local experiences and style, and weaving their own futures.

An Ongoing Relationship

The David Arment Southern African Collection at the Museum of International Folk Art, donated by David Arment and Jim Rimelspach, was the impetus for Weaving Meanings. Based in Santa Fe, Arment and Rimelspach have been traveling to South Africa for over thirty years. Their extensive travels overlapped with the development of telephone wire as an art form and resulted in a diverse and comprehensive collection that brings together telephone wire works in various creative styles and forms, highlighting both individual artistic agency and collaborative projects. In particular, the David Arment Southern African Collection is an important archive of the works of master weavers no longer with us, such as Dudu Cele (1970-2002), Bheki Dlamini (1957-2003), Elliot Mkhize (1945-2020), Jaheni Mkhize (1953-2009), and Vincent Sithole (1970-2011).

Weaving Meanings is part of MOIFA’s ongoing commitment to generative relationship-building with South African artistic communities. As part of the model of reciprocity at the center of the Weaving Meanings community-focused curatorial practice, an artists’ workshop was held in March 2024. Weaver Ntombifuthi (Magwaza) Sibiya and others had called for artist training focused on documenting artworks. Though it was not part of the original exhibition purview, the MOIFA team facilitated a professionalization workshop. Muziwandile Gigaba and Zinhle Khumalo, an arts workshop facilitator working with the arts professional development start-up curate.a.space based in KwaZulu-Natal, led an on-site program, “Empowering Artisans: Weaving Dreams Workshop.” The goal of the workshop was to nurture artists and focus on the specific skills of photographic documentation, building an online presence, developing a business network, and writing artists’ statements and biographies. The team is currently developing educational materials that will be shared directly with South African educators to support Indigenous arts curricula.

–

Dr. Elizabeth Perrill is professor of Art History at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and the guest curator of iNgqikithi yokuPhica/Weaving Meanings: Telephone Wire Art from South Africa at the Museum of International Folk Art. This article was written with extensive editorial input from the community curator and lead Indigenous knowledge expert for iNgqikithi yokuPhica, Muziwandile Gigaba, a multimedia artist and oral storyteller based in KwaMashu Township, Durban, South Africa, and Lillia McEnaney, a museum anthropologist and independent curator. McEnaney is also the assistant curator and project manager for iNgqikithi yokuPhica at MOIFA.