Collaborative Listening in a Time of Emergency:

Candice Hopkins and Raven Chacon

By Joelle E. Mendoza

Seated in a circle, the crowd patiently waited for the sold-out performance to begin. A static image of the Navajo Nation’s volcanic Church Rock was projected onto a white wall in a dark room. There was no podium. No mic stand. No stage. Raven Chacon and Candice Hopkins sat side-by-side in the circle. The performance began as the image moved and seemingly pulsated. Chacon grunted and breathed heavily with the volcanic rock. The visual movement and sounds illustrated the life of the sacred formation on Navajo Nation land.

In January 2024, SITE Santa Fe and the MFA in Studio Arts Program at the Institute of American Indian Arts presented Dispatch, a score by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer and artist Chacon, and internationally distinguished curator and writer Hopkins. The score is Chacon’s and Hopkins’s collaborative response to the Water Protectors’ defense of Standing Rock during the 2016 No Dakota Access Pipeline (#noDAPL) movement.

In his introduction, Dr. Mario A. Caro affirmed that Indigenous art “transforms, circulates, and lives with us,” and said that Hopkins and Chacon are leading the way in defining contemporary Indigenous arts. Their work is collaborative as professional artists and as life partners. I knew Hopkins as a writer and curator, and Chacon as an artist and composer, but I had not thought of them as collaborative artists until this performance. Hopkins is a citizen of Carcross/Tagish First Nation and originally from Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada. She is the director of the Forge Project in Taghkanic, New York, and a fellow in Indigenous Art History and Curator Studies at Bard College, along with curating seminal exhibitions worldwide. Chacon is from Fort Defiance, Navajo Nation, and received a 2023 New Mexico Governor’s Arts Award and a 2022 Pulitzer in music for his composition Voiceless Mass.

In Dispatch, Hopkins, Chacon, and three Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) MFA students, Kimberly Fulton Orozco, Ursula Hudson, and Mekko Harjo, along with artists and musicians Heather Trost and Laura Ortman, wove together images, sonic and visual artifacts, archival documents, and live music—which included violins, drums, singing and disruption, and even snacks (coffee and cake). Throughout Dispatch, Trost and Ortman played the violin, which enhanced the material and challenged the audience to listen closely. While Chacon and Hopkins seemed to have a structured script, it was unclear if the musicians were playing from memory or improvising. As a whole, the performance carried both the carefully timed flow of images and performers while also inserting moments of levity, jokes, and instrumental jazz-like qualities, which conveyed a mindful, purpose-driven momentum.

“Dispatch” means “to send off to a destination or for a purpose,” so instead of a traditional program, the audience was provided a zine-like booklet that offered guidance, reflection, and dialogue. Unfolded, one side had a black-and-white photo of Church Rock. The other side included a Coda with dispatches and prompts. The Coda explained how in 2016, a delegation of five women, Dr. Sarah Jumping Eagle, Wasté Win Young, Tara Houska, Autumn Chacon, and Michelle Cook, uncovered the funders of the pipeline (from banks to private corporations) and made a public call for them to divest. They traveled to Norway and Switzerland in 2017 to meet with banking personnel about the detrimental impacts of investments on community land and the violations of Indigenous rights. The Norwegian bank, DNB, decided to completely divest, but others have “yet, to heed their call.” The program invited engagement with the score’s objective: To think critically about the #noDAPL movement and how it can inspire other communities to dispatch action for other land, human rights, or social justice concerns.

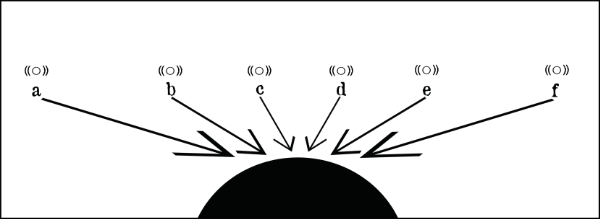

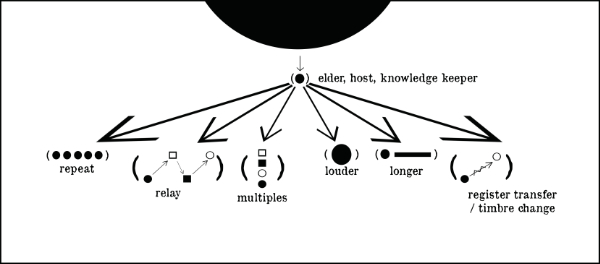

Instead of a traditional three-act structure (setup, confrontation, resolution), Chacon and Hopkins arranged an alternate three-act composition: The Call, The Gathering, and The Aim. Each dispatch served as an open invitation or dialogue with audience members to inspire action in their own communities. Just as live performance or music changes with context, they imagined this score to be “enacted in the real world.” In the call to action, Chacon and Hopkins prompted a critical examination of the players (people needed to generate attention), such as those on the front line, including reporters, politicians, artists, protestors, and spiritual leaders. The Aim asked for a critical examination of the action: What is needed, what is the leadership model, and what are the risks? These three dispatches were included in the zine and addressed in the performance through observations from the field, artifacts like historic documents, or storytelling from family, friends, and oral traditions.

About halfway through the performance, Chacon read from the 1969 bulletin manifesto, Indian Theater: An Artistic Experiment in Progress, created by IAIA director Lloyd Kiva New and drama/dance instructor Rolland Meinholtz. Projected pages from this document explained that an evening of “Indian theater” would present a series of short events that “would have an emotional pattern, but not necessarily an intellectual cohesiveness.” While Dispatch as a score included sound and music, the non-linear form was driven by emotion-filled harmonics and rhythms that took the audience on varied listening journeys and expanded on the 1969 ideas and model.

Throughout, I found myself at times completely present with the images and documentation presented, and at other times the performance opened space for me to get lost in my familial and community reflections. The score asked the audience to listen to field recordings of Standing Rock and the Water Protectors, participate in moments of call and response, and critically engage with written excerpts from artists and scholars like Fred Moten, Dylan Robinson (Stó:l/Skwah), and Pauline Oliveros that were read aloud. Like Indian Theater, Dispatch highlighted the ways communities have the power to cultivate their own ceremonies and rituals.

Hopkins, Chacon, and the other performers cultivated a socio-political performance that engaged all the senses. Hudson’s live drumming and singing explored personal memories and she invited the audience to participate by humming and singing along with her, and most did. As friends and folks around me began to participate, there was an active awareness of a powerful collective harmony. Harjo then entered the space, claiming to be late, and asked the audience to help him bring in a table, cake, and coffee. Many audience members weren’t sure if they were allowed to get up until Harjo and Hopkins announced a snack break. I used this time to get up and stretch and hug a friend. During the ten-minute break, people were able to move their bodies and stand in the center of the circle with food and friends. Unlike most academic talks or performances, this invited the audience to break the fourth wall and physically enter the circle. Hopkins and Chacon understood the whole space and performance as a stage, and this moment invited the audience to participate in a shared experience as performers.

Dispatch forced me to think critically about performance and how we are always—consciously or unconsciously—engaging in a mode of performance. Even as members of an audience, we embody certain ideas of performance expectations and roles. Chacon and Hopkins asked us to disrupt our ideas of those roles and invited us to be active, sing along, get up at the mid-point to stretch the body and eat, and mix poetry with academic scholarship and visual/audio artifacts. At the beginning of Dispatch, the room was dark as Hopkins stated: “Raven describes music as beauty lining up with other beauty. … It’s the universe reminding you that it’s listening to you. It might be repeating sounds, it might be overlapping sounds, it might be a ceremony of sound to break the spell or convention of time that we’ve been forced to adhere to. Music is the basis for everyday ceremony, just as art is the basis for every ritual.” While Hopkins provided this definition, I could hear Trost and Ortman playing the violin but could not see them. Chacon’s expansive experimental definition of the musical score mirrored this, inviting us to expand our ideas of what music is.

Hopkins and Chacon met in 2010 in Winnipeg, Canada, at Plug In Institute for Contemporary Art. Hopkins co-curated the exhibition Close Encounters: The Next 500 Years with Lee-Ann Martin (Mohawk), Jenny Western (European, Oneida, and Stockbridge-Musee), and Steve Loft (Mohawk, Jewish), and invited the collective, Postcommodity, which at that time comprised Chacon (Navajo), Kade L. Twist (Cherokee), Nathan Young (Delaware/Kiowa/Pawnee), Steven Yazzie (Laguna/Navajo), Before the exhibition, all the artists and curators participated in a month-long residency. This residency culminated with the exhibition, Hopkins’s and Chacon’s first collaboration.

At the Plug In Institute, more than thirty international Indigenous artists were interrogating and responding to what the next five hundred years could look like for humans. The Close Encounters program stated that these Indigenous artists were “radically reconsidering encounter narratives between native and non-native people, Indigenous prophecies, possible utopias, and apocalypses.” The exhibition invited Indigenous artists to engage with the “speculative, the prophetic, and the unknown.”

Chacon participated in Close Encounters as a member of Postcommodity, a collective of “proud descent of the American Indian self-determination movement that seeks to contribute to the larger postcolonial Indigenous narrative of social, cultural, political and economic perseverance.”

“To be honest, I had never seen people work together in the way Postcommodity was collaborating, which was really intriguing,” Hopkins says. “I was intrigued by the space of experimentation. I was interested in the visual arts experimentation but had never seen experimentation so profoundly within music.”

While Close Encounters was the professional crossroads at which Chacon and Hopkins met, it was also the beginning of their life-partnership origin story.

Hopkins shares that one night when Postcommodity performed a set, “It was kind of amazing, they had a homemade amp and speaker, and they burned the speakers. At the end of the set, there was a ring of fire.” Throughout the residency, they spent more time together and Hopkins credits Chacon for “wowing” her with his karaoke skills of a David Bowie cover. Chacon claims Hopkins was and continues to be “the most brilliant person I’ve ever met.”

Their relationship developed further outside the residency, and they ultimately relocated to Albuquerque. As they continued to advance their individual art careers, they also continued to collaborate.

“Before I knew Candice, I was very nomadic and constantly on the road,” Chacon says. “Ever since I left CalArts, I was always town-to-town. In a lot of ways, I am still, but I think it has lined up with the ways Candice’s life had also been […] but for me, now, I am able to move with her.”

Both attribute their professional and personal successes to the places that they come from and the communities they’ve built. Hopkins explains, “Beyond us, we have incredible family and community. Raven’s family is amazing—his mom, dad, and grandparents are all incredible people. On my end, I like to say I come from a long line of really tough women. So, our worldviews really align, and we have a lot of support from extended relations. We cannot do this on our own because we live a fairly unconventional life.”

In December 2015, Chacon and Hopkins transformed an empty lot that was left by the construction that widened Lomas Boulevard in Albuquerque into a space that has hosted experimental artists and projects ever since. Their space, Off Lomas, hosted Battle at Fort Lotaburger byIndigenous artists Autumn Chacon, Fish Water, and Eugene Yazzie in November 2017. This sound installation and radio broadcast highlighted the experience from the frontlines of the Water Protectors at Standing Rock during the #NoDAPL movement, which is also referenced in Dispatch score. These audio recordings include the sonic layers of the place, which include singing, bullhorns, police, prayers, and drones from the front lines.

While Hopkins and Chacon have different careers, they each critically and creatively support the other’s daily practices, often reading or listening to each other’s first drafts of ideas or projects.

Chacon’s worldview and Diné teachings have shaped his role as a supportive partner to Hopkins. “I learn from Raven about composition, about timing, about expanding definitions of music,” Hopkins says. “And one of the things I can do is translate—curate and work through ideas.”

For Chacon, Hopkins’s perspective as a curator influences his thinking about the informal ways he organizes artists, musicians, and projects. “I’ve never considered anything I did in the past curating, and I’m not sure that I still do, to the level that a curator works, but I’ve been able to understand [that role in] the smaller projects I’ve done like running a label, DIY space.” Like a curator, Chacon connects larger themes and communities for a shared vision.

Dispatch is the third score Hopkins and Chacon have collaborated on. In 2014, they co-wrote Score for Marginal Objects; in 2017, they co-wrote Score for Hearing Voices. When collaborating on these scores, there is “reciprocal critical thinking,” Chacon says. Together, they “consider all the possibilities” and then test and challenge it with their community. While writing, Chacon shared that they both ask themselves, “One, what are we trying to say? Two, is it important to say? And three, can it actually be realized?”

Dispatch started with conversations after coming back from Standing Rock in 2016. For Chacon, the experience at the encampment was surreal and profound and he was struck by the many different sounds that emerged from so many people living and protesting together at Standing Rock. “I’d been thinking through my experience there in a sonic analysis, I suppose,” Chacon says.

In 2020, Hopkins and Chacon were scheduled to collaborate with environmental art organization Liquid Architecture in Melbourne, Australia, but the trip was canceled due to COVID-19. Both Hopkins and Chacon had planned to use that time to work on a score based on the #noDAPL movement and response to Standing Rock.

Home-bound in New Mexico, they had to reorient their approach to the project. In the early months of the pandemic, they often took long drives where they practiced and exercised different listening methods. The concept of “deep listening,” coined by composer and performer Paulina Oliveros, was something Hopkins and Chacon reflected on. Dispatch is featured within The Center for Deep Listening, an organization that provides workshops and retreats for the practice of deep listening. “In order to deep listen, you can’t cancel out the sounds you don’t want to hear,” Hopkins says. When Chacon returned from Standing Rock, he asked, “How do you listen in times of emergency, when you don’t have the privilege of silence, or your life might be under threat? How do you hear in those times?”

Chacon and Hopkins both wanted to think about how Dispatch could be re-imagined for other scenarios and places outside Standing Rock. The idea for creating an adaptable score came when Hopkins and Chacon visited Coaxial, a multi-disciplinary media arts organization in Los Angeles. A visiting musician from Melbourn shared stories of activism there to protect sacred trees that were threatened by freeway expansion. For Dispatch, Hopkins and Chacon thought about the conditions and the players, but also how the score could be transferable, which is why Dispatch has three parts (The Call, The Gathering and The Aim). Part of their process included writing down experiences and then brainstorming prompts and transposing them onto other contexts—such as other environmental sites that were under threat or even Confederate monuments that still need to be removed.

When they collaborate, Chacon and Hopkins are weaving in their communities, too. In writing Dispatch, they invited collaborations from Cannupa Hanska Lugar and other musicians to explore the composition further. As Hopkins shared during the score, with violins playing softly underneath her voice, “The politics of colonial entanglement offer the possibility not only to hear but to listen to their silences as well.”

“When people have historically been silenced, […] there are things that need to be said, there are things that need to be confronted,” says Chacon. Both Chacon and Hopkins shared ways they examine listening and the ways they listen to the land, in addition to examining what worldviews threaten the land. They both remind us of this in the zine and in their spoken words when they perform in Dispatch. “Rocks have harmonics, resonated frequencies. They are also deities, lives begun millions of years ago, witnesses to the formation of the earth,” says Candice.

Chacon and Hopkins shared that collaborative feedback from trusted community members, including other artists, musicians, and students was part of the process of writing a score. Improvisation is at the “heart of resistance movements,” Hopkins states, “It can be the place where all songs are welcome, where all rhythms are accepted.” As with any live performance, no performances will ever be identical.

Chacon and Hopkins are sounding boards for each other and continue to find ways to support one another’s careers. Hopkins shares, “My role in this world is to be a conduit and offer people platforms.” As individual artists and collaborators, both Chacon and Hopkins illustrate that the objective is not simply about the product, but the process of the work.

At the end of the Dispatch, I remember sitting still before turning to a homegirl who said, “Damn, they collaborate as artists and still have to live with one another.” We shared a laugh. Later, when I asked them how they weave ideas of deep listening into their daily practice and partnership, Hopkins admitted, “the truth of the matter is we don’t always listen as well as we should.” However, they both affirmed that they are committed to a shared vision and exploring how to be better listeners within their practices.

“One thing we share, at the end of the day, is that we’re very positive about art and what artists are doing,” Chacon says. “And the potential of art and what it can do,” adds Hopkins. Chacon continues, “We believe in art, and we believe in artists.”

—

Joelle E. Mendoza (JEM) is an Indigenous-Chicana artist and writer based in East Los Angeles. JEM holds an MFA in Fiction and Screenwriting from the Institute of American Indian Arts. She also works with clay and adobe along with contributing to local Native gardening practices and collectives.