The Art of Survival

The Aftermath of the Deadly 1980 New Mexico State Penitentiary Riot

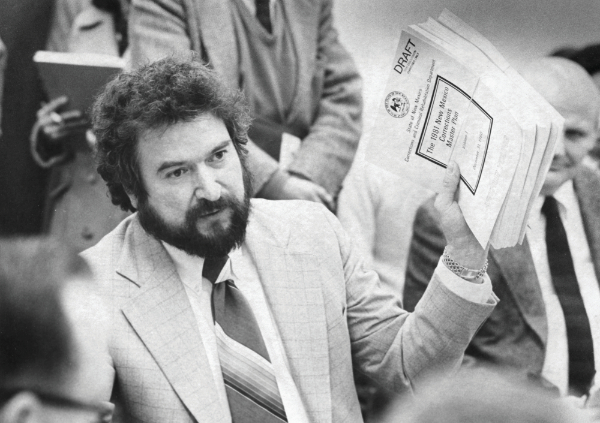

Mark Lennihan, State Senator Charles Marquez, leader of prison reform, 1981. Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo

Archives (NMHM/DCA), The Santa Fe New Mexican Collection, HP.2014.14.2644.

Mark Lennihan, State Senator Charles Marquez, leader of prison reform, 1981. Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo

Archives (NMHM/DCA), The Santa Fe New Mexican Collection, HP.2014.14.2644.

By Stephanie Joyce

The engraving on the side of the cup is painstakingly scratched out of the silver metal. The top line reads “PNM”—the Penitentiary of New Mexico. Below are two simple statistics that together tell a brutal story with remarkable concision.

“33 DIED,” reads the second line.

“89 WOUNDED,” reads the third.

Paul Oliver remembers the day his father, Nordaine Oliver, brought the cup home from work. Nordaine was a guard at the state penitentiary, just south of Santa Fe, and the engraving needed no explanation. Even as a teenager, Paul knew it referenced the 1980 riot at the prison, widely considered to be one of the most violent in U.S. history. While Nordaine hadn’t been on duty in the early morning hours of February 2 when the riot broke out, according to Paul, he had been among the law enforcement officers who helped retake the penitentiary after a thirty-six-hour standoff. What Nordaine saw inside had haunted him, which is perhaps why he didn’t explain much about the cup and the prisoner who had made it—and why Paul didn’t ask.

“One thing my father did say is out of two wars that he had been through [Korea and Vietnam], he had never seen more gruesome mutilation of humans than what he saw after the riot, going through the penitentiary,” Paul recalls.

Perhaps the cup was a declaration of survival from someone who had lived through the riot; perhaps it was a memorial to those lost. As with many of the pieces on display in Between the Lines: Prison Art & Advocacy, an exhibition currently on view through September 2, 2025 at the Museum of International Folk Art, it’s unlikely we’ll ever know the full story behind it. But the questions the cup raises about the human compulsion to create art out of tragedy, and to document our experiences, are among those explored in the exhibition. Overall, Between the Lines asks visitors to reflect on the purpose of imprisonment and its ripple effects in communities, including Santa Fe.

When the state penitentiary opened at its current location just off Highway 14 in 1956, then-Governor John Simms called it “among the most advanced correctional institutions in the world.” The previous penitentiary in downtown Santa Fe had been plagued with overcrowding and violence, leading to a riot at the facility in 1953. Once the new prison was built, its first warden, H.R. Swenson, touted its potential for rehabilitation rather than simply punishment, saying that with the improved physical conditions of the penitentiary, “we elevate our sights, and begin the task of human repair.” He imagined a future that included educational services and community programs that would help prepare people locked up for new lives upon release—a vision that was at least partly realized in the early years of the new prison. But many of the problems that had plagued the previous facility, including poorly-trained guards and over-crowding, soon became problems at the new penitentiary and by 1975, operation of the prison had become “a challenge to all concerned,” according to then-Secretary of Corrections, Michael Hanrahan.

A veteran of the federal maximum security prison system was appointed as the new warden that same year, and according to a report from the Attorney General in the aftermath of the riot, he “supported a philosophy that promoted tighter restrictions on inmates.” One of the warden’s first moves was to reduce the programming available to those inside. As a result, many prisoners found themselves idle for large stretches of the day, and the guards lacked the means to motivate good behavior. “Human beings function better when they have some self esteem and incentives in their lives,” the Attorney General’s report noted. But those incentives were in short supply by the late ’70s, when Carlos Cervantes was sentenced to the state penitentiary.

Growing up in Santa Fe as a middle child of ten, Cervantes discovered a talent for art at an early age. At the Boy’s & Girl’s Club, he learned the techniques of woodburning, carving, and drawing, winning several awards for his work. Like many children of the 1960s and ’70s, he often used his art for protest, participating in El Movimiento, the movement for Chicano power. Then, when he was twenty-four, he was arrested for selling heroin and sentenced to a minimum of thirty-four years in prison.

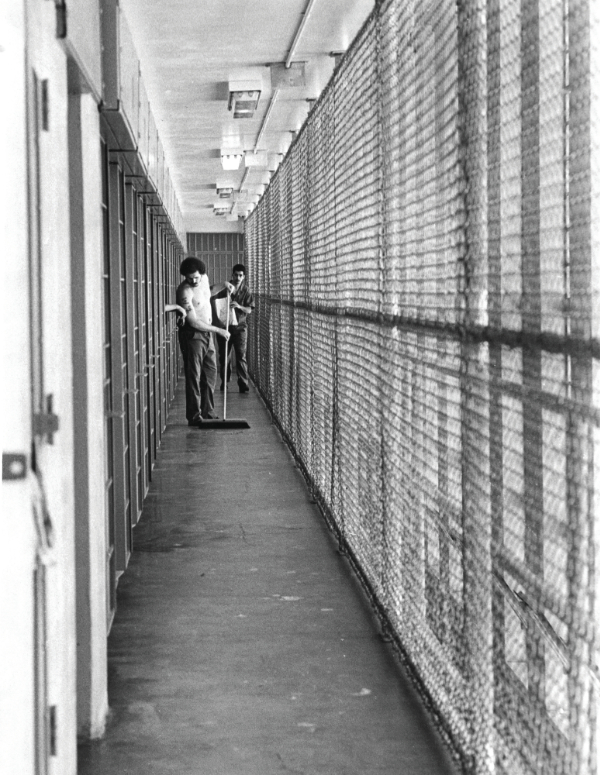

Cervantes arrived at the penitentiary in 1978, which was a particularly volatile moment. The prison was overcrowded, with more than 1,100 people crammed into a facility built for less than 1,000, and guard turnover was at eighty percent. According to the Attorney General’s report, an atmosphere of hostility prevailed between the guards and those incarcerated. “The distinctions between minor and major violations were not clear,” the report said. “Inmates reported that the guards threatened lockup for such offenses as walking down the wrong side of the corridor, lying on their bunks after reveille, disruptive conduct, verbal abuse against staff members, failing to follow a direct order, or taking crackers out of the kitchen.” Three independent filmmakers spent time in the penitentiary in 1979 and documented bubbling anger among the prisoners over conditions in the film Doing Time. “Rehabilitation is out now,” one prisoner told the filmmakers. “You’re here to be punished, okay? And they don’t make no bones about that anymore. That’s a fact.”

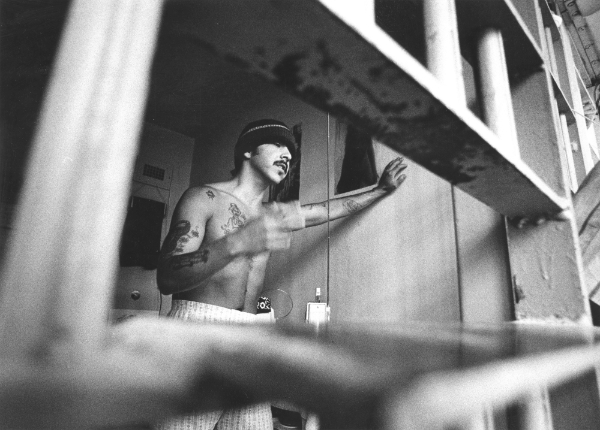

Despite the dearth of rehabilitative programming, many incarcerated people nevertheless found ways to make art. Cervantes was among them. In prison, as on the outside, people make art for many reasons. It can be a form of personal expression, a means of protest, a remedy for boredom, and a valuable commodity—or sometimes all of the above. For Cervantes, the main constraint on his work inside the prison was the availability of materials and tools, although he quickly learned to improvise. Like generations of incarcerated people in the Southwest before him, he ripped up bedsheets to create paños (handkerchief-sized canvases for drawing), built rudimentary tattoo machines out of scrapped materials, and hoarded the wrappers from cigarette packs to craft into intricate picture frames. A video featured in Between the Lines shows his technique of carefully cutting apart the wrappers with a razor blade to make smaller pieces, folding those pieces into strips, and then painstakingly weaving the strips together to build colorful three-dimensional frames. “It would take me out of prison,” he says. “It was an escape.” But while Cervantes was channeling his energies into making art, other prisoners were planning how to take over the prison.

The riot began in the early morning hours of February 2, 1980, in a part of the penitentiary known as Dormitory E-2. E-2 was considered a medium-security unit, but a number of higher-security prisoners had been transferred there during construction on one of the cellblocks. The riot, according to witnesses, broke out when several of those prisoners seized four guards as they were locking down the dormitory for the night. Taking those guards’ keys, the rioters unlocked the doors to adjacent dormitories and cellblocks, capturing another four guards in the process. According to the Attorney General’s report, in twenty-two minutes, they had broken into the penitentiary’s control center, and within hours, they had total control of the facility.

While prison riots were far from unusual in the U.S. at the time—there had been thirty-nine riots in U.S. prisons in the 1970s alone—the speed and scale of the rioters’ takeover made the situation in Santa Fe unique, as did the violence that ensued. Of the seventeen listed as employees on duty at the prison on February 2 according to the Attorney General’s report, twelve ended up being taken hostage. Many of them were beaten, stabbed, and sexually assaulted. But the guards were not the only ones who were targeted. Much of the violence was directed at other prisoners, especially those housed in Cellblock 4, which was widely understood to be a protective custody unit for prison informants. Eyewitnesses reported that a group of 15-20 rioters formed what was referred to in the Attorney General’s report as “a death squad” that proceeded to conduct “a systematic killing campaign” in the cellblock.

Partly due to a stroke he suffered several years ago, Cervantes struggles to tell his story of that day, but according to written accounts, as the chaos spread, he left his cell on the south side of the prison and ended up on the north side of the facility. There, he and a number of other prisoners worked together to protect two guards from the atrocities that were unfolding elsewhere. “I am certain that his protection helped to save my life,” one of the guards later wrote, noting that Cervantes had stayed with the officers for most of the riot, “making sure that no harm came to us from other inmates.” Many others were not so lucky. By the time SWAT teams and National Guard troops retook the prison a day and a half after the start of the riot, at least thirty-three prisoners were dead, and dozens, if not hundreds, of others had been gravely injured.

Patricia Cervantes, Carlos’s sister, remembers waiting outside the prison with her entire family for any news about her brother. “All these guys [coming out of the prison], their faces were just black from the smoke,” she said. The rioters had set fires all over the penitentiary, including in the warden’s office and the records department. As they waited, Patricia says the family checked and rechecked the lists of names of people who managed to escape and surrender to police, but Carlos’s name never appeared. “We were really scared,” she said. It was only when the prison had been retaken that Carlos’s family spotted him on a bus transporting prisoners to the airport so they could be relocated out of state. Even now, decades later, Patricia gets emotional thinking about the moment. “We followed the bus, and we went [to the airport],” she remembered. “They didn’t let any of us really get near him, but we were all watching from a distance.” Within hours, Cervantes, along with dozens of other prisoners, was on a plane bound for Arizona—his first time leaving New Mexico.

The riot brought considerable scrutiny to the penitentiary, but reforms were slow to come in its aftermath. Lax security, insufficient guard training, harassment of prisoners, an absence of programming and arbitrary use of punishment were all identified by the Attorney General’s report as factors that had contributed to the riot. An investigation by the Santa Fe Reporter a year later found that if anything, the riot made many of those problems worse, noting that there had been a “post-riot regimen of brutality, caprice and incredible security lapses.” Three years prior to the riot, a prisoner named Dwight Duran had filed suit against the state, alleging that conditions in the penitentiary violated incarcerated people’s constitutional rights. The state signed what would become known as the Duran Consent Decree in July of 1980, an agreement to make improvements to the state’s prison system in fourteen different areas, including medical care, legal access, and living conditions, but the changes went largely unimplemented for years. A former guard told The New York Times in late 1981, “It just hasn’t changed—it’s gotten worse since the riot.” According to that same article, nine prisoners and two guards were killed inside the penitentiary in the two years after the riot, and the number of incarcerated people allowed to participate in any kind of educational or community programming dropped to a mere ten percent. “Human repair” seemed a distant memory.

Over the course of the 1980s, the state expanded the physical footprint of the penitentiary, building three new facilities on the eponymous Penitentiary Road, including two new maximum security complexes and a minimum-security prison. But a decade later, the general consensus was that the penitentiary was still operating far from optimally. “They’ve got much better security than they had in 1980. They’ve got a much better guard training program than they had in 1980,” Karen McDaniel, a reporter for KOAT, said in the 1990 documentary, At Week’s End: Since the 1980 Riot, which is screened in Between the Lines. “But there’s still a lot of problems.”

For Cervantes, the 1980s were a tumultuous decade. After being transferred out of New Mexico, he was bounced around the country to prisons in Arizona, Indiana, and Oklahoma. In Santa Fe, his family visited regularly on the weekends, but out of state, Cervantes found himself on his own, surrounded by people with very different backgrounds and life experiences. As before the riot, he escaped into his art. Prison art is often regional, with specific techniques dominating in different parts of the country and among specific populations. Cervantes quickly learned that many of the art forms that had been commonplace at the penitentiary, including paño drawing and crafting cigarette-pack picture frames, were totally novel in out-of-state prisons. “He’s talked about how they admired his artwork and the little frames that he did,” Patricia said. “He taught them something they had never seen before in prison.”

Then in 1985, Cervantes ended up back in New Mexico. He attributes the commutation of his sentence by then-Governor Toney Anaya to the help he had provided to the prison guards during the riot. He was out of prison but remained on parole. As with many who experienced the riot first-hand, Cervantes rarely talked about what had happened, but it continued to loom large in his life and his community.

While Paul Oliver grew up understanding that the story of the riot inscribed on the cup his father brought home was a horror story, the version John Paul Granillo learned was very different. Unlike Oliver, Granillo was not even born at the time of the riot, but nevertheless grew up in its shadow. By the time he was learning about it in the 1990s, it had become almost a legend in his neighborhood near downtown Santa Fe. Granillo remembers his neighbors treating those who had been imprisoned during the riot with deference—including Cervantes, who was close friends with Granillo’s grandfather.

“We called them veteranos—veterans,” Granillo explained. “It was cool to be that.” Looking back, Granillo can see that underneath the mythology was a tremendous amount of pain and unspoken trauma around the riot, and the violence that had been perpetrated, but at the time, the lesson he internalized was that the violence had made the veteranos tough, and that he should be tough too. “You wanna be as badass as Johnny Badass, right?” It wasn’t until Granillo himself ended up in federal prison for bank robbery that his perspective on the events of February 2 and 3, 1980 started to shift, and he saw the ways the riot had damaged people. “It is a trauma that poured out in a lot of different ways,” Granillo said. “They’re still hurting.”

Today, prison riots are relatively rare, despite the fact that the prison population in the U.S. has ballooned since 1980. Even after many prisoner releases during the COVID pandemic, the overall prison population is nearly four times what it was at the time of the 1980 riot, according to data from the U.S. Department of Justice. New Mexico’s prison population has followed a similar trend. There are a variety of reasons for the precipitous rise in prison populations, but chief among them are an increase in the length of sentences and more effective prosecutions. There isn’t much scholarship that examines why riots have fallen by the wayside in the U. S., although the rise of specialized riot-control units within prisons and increased use of lockdowns and solitary confinement are often cited as plausible causes. In other words—restriction and force, not access to programs or better overall conditions.

The facility at PNM that housed incarcerated people in 1980, known as Old Main, was shut down in 1998, and today it is used as a film set for movies. It’s also open to tour groups—“Public Tours, Group Tours, School Tours, Historical Tours,” as the Corrections Department website advertises. For a fee, a department employee will walk visitors through Old Main’s weathered cellblocks, narrating the story of the riot. The guiding motto for the tours is, according to the Corrections Department, “respecting our past to create a better future”—a tidy narrative of linear improvement. Reality, however, is not so neat. Reforms aimed at addressing prison crowding, conditions, and programming have waxed and waned over the past decades according to the priorities of each incoming administration. One of the strengths of Between the Lines—which showcases art from incarcerated people across the country and internationally—is the way it highlights the challenge of changing the system of mass incarceration.

The commutation of Cervantes’s sentence in 1985 was not the end of his story with the state penitentiary. He would end up spending another fifteen years of his life locked up in the state prison system as he cycled in and out of detention throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, sometimes for new drug-related charges, sometimes for parole violations. Now seventy-one years old, he remains on parole.

Both in and out of prison, Cervantes has continued to make art, including many murals in both Santa Fe and Albuquerque. One of his most elaborate works is in a small community park on the Santa Fe River, near the intersection of Alameda and St. Francis Drive. Most of Louis Montaño Park is a labyrinth of color, full of bright geometric designs and depictions of Aztec religious icons. But near the top of the park is a very different kind of piece—a self-portrait of the artist. In it, Cervantes sports a bushy black mustache with upturned corners, a style that remains his signature today. He peers out from behind bars in a blue prison jumpsuit labeled with his prisoner number: 27480. A guard tower looms over him, wrapped in a hissing snake, and an hourglass beside him marks the slow passage of time. Cervantes is half-smiling in the portrait, giving the impression of defiance, an unwillingness to be reduced to the cage he’s in.

Granillo remembers Cervantes painting the murals in the park. It inspired him to his own artistic practice, which he got serious about in prison. Drawing and painting were a way to pass the time, but over the years, Granillo also came to see a deeper significance in the act of creating. “If you don’t make your mark for you, they have a place to put you,” he said, explaining that during his time in prison, he had come to see art as an act of resistance against a system that often reduces incarcerated people to statistics. 33 died, 89 wounded. That’s also, Granillo believes, the power of Between the Lines. He was one of many community collaborators on the exhibit, which features some of his own work, as well as the work of other artists he connected to the museum. Over the years, Granillo has noticed that people who receive art from prisoners often hide the pieces away—out of shame, or pain, or a desire not to dwell on its provenance. That was the case for the cup Nordaine Oliver received—Paul says after the day his father brought it home, he didn’t see it again until three decades later when he was sorting through his father’s belongings. By bringing those pieces out of storage and into the museum, Granillo is hopeful that visitors will walk away thinking about the people who made them and why. “I think in this exhibition, they’re bringing back a lot of —humanizing, some of the dehumanizing that happened in those spaces,” Granillo said. “And I think that’s how [prisoners] remember they’re human in prison too. It’s through the art.”

—

Stephanie Joyce is a freelance journalist based in Santa Fe.