Returning Home

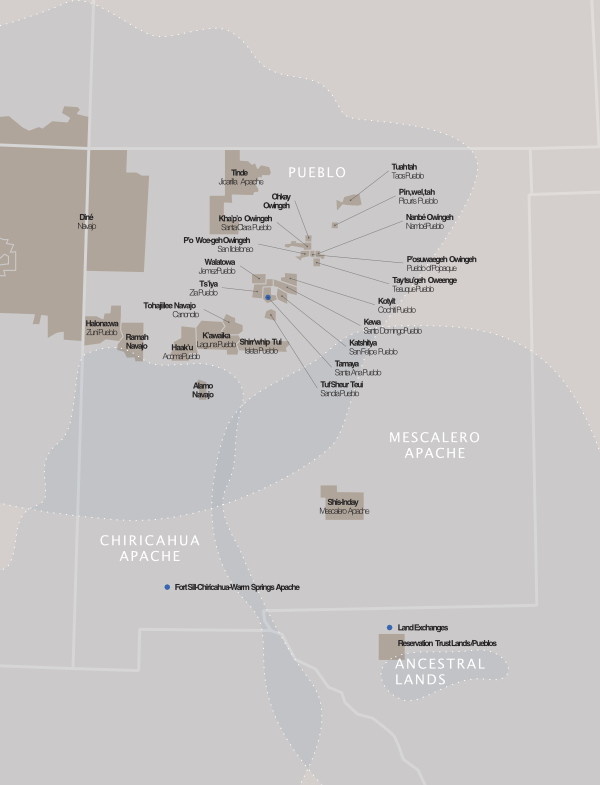

Two Sovereign Nations Reclaim Land Following U.S. Government Extraction, Removal, and Displacement

Santa Ana land acquired in the 2021 land exchange with

the State of New Mexico, 2024. Courtesy of Santa Ana Pueblo.

Santa Ana land acquired in the 2021 land exchange with

the State of New Mexico, 2024. Courtesy of Santa Ana Pueblo.

By DezBaa´

Santa Ana Pueblo / Tamaya

Santa Ana Pueblo calls itself Tamaya and its people, the Tamayame, speak Keres. To the rest of the world, however, it is known as Santa Ana Pueblo because it is the official government title for the sovereign nation. Santa Ana currently encompasses 79,000 acres of land northwest of Albuquerque and borders Bernalillo to the south.

For the most part, the Tamayame have been able to maintain being on their homelands in the Rio Grande Valley since their arrival in the region in the 1200s. The section of I-25 between Santa Fe and Albuquerque runs through the reservation. Santa Ana owns a vineyard northeast of Bernalillo on the east side of the interstate, and it sells the crop to Gruet, our New Mexico sparkling wine company.

Hidden from view of the interstate to the west, Santa Ana housing dots the Rio Grande. Driving along the frontage road, it looks ecologically similar to the area where I grew up in Northern New Mexico. Living north of Medanales and going to school in Española, my family and I would often travel along highway 84 and 285—between Abiquiu and Ojo Caliente. Driving with the windows down and the sun shining in, anyone could tell why this land has been fought for and held onto for so long.

When I first called the Santa Ana Historic Preservation Office inquiring about Santa Ana completing a land exchange with the New Mexico State Land Office, the woman on the phone chuckled. Monica Murrell informed me the Pueblo had been buying back their lands from the Spanish since the 1700s.

Murrell, the Tribal Historic Preservation Officer and Director for Santa Ana Pueblo, has previously worked for other Pueblos and Nations. She is well-versed in the bureaucratic dance that comes with working with several governments and organizations at once. She set up a meeting for me to talk with Governor Myron Armijo and his nephews about Santa Ana’s economic development, cultural preservation, and expanding land base.

Governor Armijo spoke about Santa Ana’s cultural priorities, and how his people have worked diligently for years to create its current economic environment, including revenue generated by a resort, casino, and golf courses. It wasn’t an easy decision to build the casino, but the Pueblo knew without substantial income their cultural ties to the land would be in jeopardy. Armijo sees economic self-sufficiency as a means to a much bigger goal. The revenue created by the casino and golf courses are in place only to provide the capital to trade in for something even more valuable—to buy back their stolen land.

In 2016, in a regular real estate purchase, the Pueblo paid a hefty $30 million to buy ancestral lands back from former Governor Bruce King’s family ranch. Just this summer—eight years later—this “fee land” was turned into a reservation, or trust lands, for the Pueblo. In 2021, Santa Ana acquired three additional parcels of New Mexico State Land Office inholdings within the former King property through the land-exchange program, totaling 1,920 acres valued at $912,000.

The land was already being leased to the Pueblo for livestock grazing and was exchanged for three parcels Santa Ana had purchased within Los Alamos County and an additional parcel in Bernalillo County, for a combined value of $924,000. The lands proposed for conveyance to the state had greater potential for commercial development, thereby providing greater income potential to the trust land beneficiary—New Mexico Public Schools.

As Murrell mentioned, Santa Ana Pueblo has been buying back its land through its own means since the colonial period. Almost 95,000 acres of lands between the Pueblo and the Sandia Mountains were bought back from the colonial settlers in the 1700s through the exchange of both Spanish currency and goods, such as livestock blankets, saddles, horses, cows, or whatever was available for trade. The deeds documenting these early land acquisitions are housed in a protected archive. Governor Armijo says this recently acquired land is valuable not for future economic development but is set aside for cultural use.

The amount of land granted to Santa Ana—when what is now New Mexico was a part of a colony of Spain—measured four square leagues (commonly referred to as a Pueblo league) surrounding the Pueblo’s mission, totaling approximately 17,350 acres. This land was unsuitable for agriculture. The first parcel the Pueblo reacquired in 1709 from Manuel Baca for fifty pesos. It had been owned by Baca’s father, Cristóbal, and had been a part of the Angostura de Bernalillo Land Grant. According to the authors of the 2015 book Four Square Leagues: Pueblo Indian Land in New Mexico, “[t]he pueblo paid whatever the Hispanos demanded, believing that no price could be put on land.” Reading this is heartbreaking; it’s as though our land is being held for ransom.

Governor Armijo recalls that as a young council member in the 1980s Santa Ana’s annual budget was around $10,000. It was then the council decided that even with their small budget, they would eventually buy back the land as more funds became available.

New Mexico State Land Office Land Exchanges

New Mexico has nine million surface acres held in trust for Native tribes within the state. According to the New Mexico Commissioner of Public Lands Stephanie Garcia Richard, “The State Land Office acknowledges that it is stolen ancestral Indigenous land.” However, these lands generate income to benefit public schools and other institutions. Tribal government agencies can “buy back” parcels of ancestral lands by exchanging purchased commercial real estate for the lands New Mexico holds in trust which, until exchanged, are set aside to generate money for public programs. The acreage being exchanged can be different, but the dollar amount must be equal. The trust land acreage is generally higher because the acre-value is lower.

Garcia Richard explained that the land exchange program is a “government-to-government transaction. We exchange with Federal Government, we exchange with other state agencies, we exchange with the tribes.” Of the twenty-three federally recognized Native Nations within New Mexico’s borders, only two—Santa Ana Pueblo and Fort Sill-Chiricahua-Warm Springs Apache—within the last six years under Commissioner Garcia Richard’s leadership have filed applications and purchased profitable commercial land in exchange for part of the acres held in trust by the state. According to Joey Keefe, assistant commissioner of communications with the State Land Office, both Santa Ana and Fort Sill purchased commercial land to use for the land exchange program. “Typically, a tribe will apply to the State Land Office to initiate an exchange when they have identified a parcel of state land that is culturally significant to them,” said Keefe. “Since the State Land Office cannot legally give land away […] The State Land Office assesses the value of the property the tribe would like to receive and then we work with the tribe to find an equal value parcel of land that would be financially beneficial to the State Land Office and the institutions we fund.”

The remaining land held in trust, awaiting potential exchange, can be leased by the state to generate income for New Mexico’s public schools. According to Maria Parazo Rose and Anna V. Smith, who wrote about state trust lands for Grist,

State trust lands, which are managed by state agencies, generate millions of dollars for public schools, universities, penitentiaries, hospitals, and other state institutions, typically through grazing, logging, mining, and oil and gas production. Although federal Indian reservations were established for the use and governance of Indigenous nations and their citizens, the existence of state trust lands reveals a truth: States rely on Indigenous land and resources to support non-Indigenous institutions and offset state taxpayer dollars for non-Indigenous people. Tribal nations have no control over this land, and many states do not consult with tribes about how it’s used.

The intricacies of this system are problematic. However, it can make sense for more Nations to buy back land for their own tribe’s needs. By exchanging the land for lucrative, high-value city real estate, New Mexico doesn’t lose funds from leasing trust lands to farmers, it just moves the source. And because there are a growing number of urban Natives who benefit from these state-funded public programs, this “land exchange” is a win all around. While this commonwealth approach is in line with Indigenous land values, it entails private purchases that encroach on the culture of Indigenous Natives and New Mexicans who’ve been “born here” all their lives.

Cities continue to expand as folks outside of New Mexico with deep pockets look for quiet, expansive blue skies, and large sections of land. The Wild West continues to beckon adventurers and fortune seekers. But this wildness, this mountain-desert landscape, for some of us, is more than just land we can build a fence across to claim as “property.” It’s a relationship we have with the land. A kinship. And kinship is vastly different from ownership.

The difference between ownership and kinship is based on perspective. One perspective values the land as a living entity. The other promotes superiority and dominion over the land—including animals. Inherent in this latter perspective is a dissociation on multiple levels that positions the owner in isolation from everything around them. Continuing to pursue the act of ownership perpetuates the inherent disconnect. This cycle grows like a cancer. The more we set to own, the less we have viable relationships with.

A History of Displacement

The Native people of this land were systematically and forcibly removed and relocated. Of approximately 575 federally recognized Nations and tribes in the United States today and the four hundred unrecognized tribes, only a handful live within their original territories. Many reservations are lands where the U.S. government discarded Indigenous people. These Native homelands became what the U.S. needed to create its empire: A new nation as far from the restraints of the British, and out of the hands of competing European nations, as possible.

The irony of removing Indigenous people from their homelands to provide the space for a growing U.S. to prosper and live freely is not lost on Indigenous people. Reservations, in essence, were created as glorified incarceration camps to keep Indigenous people off American soil. No matter how the government tried to package these deals or what promises and agreements were brokered between the U.S. and tribes, it has been incredibly difficult for the tribes to recover from these acts of violence, and the U.S. government made it nearly impossible for the tribes to re-establish themselves as self-reliant governments.

Prior to invasion, Indigenous people have inhabited what is now the United States. Prior to becoming a state in 1912 and prior to the arrival of the Spanish in the 1500s, what is now called New Mexico has always been inhabited by Indigenous communities. Some of us were nomadic, and others more settled in agriculture.

This arid landscape has been one of the last holdouts in the union to be wrangled into submission. I think it’s part and parcel to who we are. Unruly. Robust. Wild. Forever untamed. Like a bucking bronco, this pocket of the Southwest continues to beckon outsiders and test their ability to survive. It tempts outsiders to commercialize its blue skies, geologic soils, and geothermal landscapes. When passing through the Navajo Nation with my partner, he remarked, “I can’t imagine anyone ever wanting to leave here.” Taking this in, I teared up and replied, “We didn’t.”

Beginning in 1863, Diné and Ndé were rounded up and taken to an incarceration camp in Fort Sumner. Bosque Redondo, known to Diné as Hwéeldi, The Place of Suffering, imprisoned Diné and Ndé for nearly five years. The conditions were beyond brutal: alkaline water, poor soil, oppressive heat—conditions that the soldiers themselves had issue with and wrote about in their journals. But if the conditions were harsh for the soldiers, the conditions were flat-out inhumane for the Natives.

After a smallpox outbreak in the Ndé side of the reservation, they decided to leave in the middle of the night. The Diné stayed until they were able to obtain a treaty with the U.S. government that allowed us to return to our homelands June 1, 1868.

A majority of Diné were incarcerated, but some remained hidden in the far reaches of the Dinebikeyah—as far away as Antelope Canyon. Others—many of them children—were sold into slavery to Spanish settlers as far north as Abiquiú. Though many Diné take pride that they managed to escape being rounded up and taken to the incarceration camp, the physical and cultural effects of hiding to survive have left a mark on all of us. Just because some weren’t taken prisoner does not make anyone immune to effects of this attempted genocide.

I did not grow up on the Navajo Nation reservation and neither did my father. I was born in Santa Fe and grew up in Northern New Mexico. My dad grew up in a reservation border town, raised by a white family who had employed his mother. Growing up in Northern New Mexico, I mostly identified as being Hispanic because of my mom’s Mexican heritage and although I knew very little Spanish, I knew a lot more than I did Diné bizaad.

In 2023, I applied for and received a grant from New Mexico Arts to create a project at Bosque Redondo Memorial in Fort Sumner. I applied for this grant to help my dad with a question he’d begun to ask five years earlier. Who am I? It was a question, I believe, he had been asking himself all his life, but it was only after I had returned home from trying to figure that out myself that he gave himself permission to ask out loud.

In 2015, I landed a job as a geologist for the Navajo Nation and so I moved with my daughter from Massachusetts to Gallup. I was terrified of being seen as an outsider and nervous about being accepted. The first day of training, after a half hour of introductions from coworkers in Navajo, it came my turn to introduce myself. I told the facilitator my clans in English, apologized for not knowing my language, and said I was glad to be back “home.” The facilitator smiled and said, “You’ve returned to us.” And in that moment, I did feel at home and I knew who I was. From the time I moved back to my homelands to the time my dad and I stepped foot in Bosque Redondo, I knew who I was, and wanted my dad to find that same sense of belonging.

When a Diné person asks another Diné, “Who are you?,” they are basically asking the other person, “Where are you from?” The responder will share their clans with the inquirer. Clans are based on geographical origin although a person may not live in that area anymore. The long-form answer would include where you were born, where you are now, your parents, and where they’re from. You end the answer: This is what makes me Diné. Our identities as Diné are intrinsically connected to land and if you don’t know your clans, then not only do you not who you are, you don’t know where you’re from.

If you take the time to think about it, all our identities are land-based. The essence of who we are as humans has always been rooted in land even if we have become disconnected from this, whether we no longer live in our countries of origin or our work no longer keeps us connected to the earth. In our global society we identify ourselves by land-based citizenship that came to us from either where we were born, where our parents were born, or because we decided to pledge ourselves to a new nation.

If our identity as a species is so tied to land, how could anyone question the validity of returning land that Indigenous people were on thousands of years prior to the arrival of Europeans? The land that became known as the “land of the free and the home of the brave” has always been a part of a Native’s identity. And that is exactly why colonizers tried so hard to take it away. If you take away a person’s identity, it is easier to destroy who they are. Kill the Indian and take their land.

Fort Sill-Chiricahua-

Warm Springs Apache Tribe

In 2011, the Bureau of Indian Affairs designated thirty acres east of Deming for the Fort Sill-Chiricahua-Warm Springs Apache Tribe as its official reservation. The Tribe purchased the land in 1998 and it was held in trust by the federal government from 2007, but it took four more years for it to be declared a reservation in 2011. For decades the Fort Sill Apache Tribe had no land to call home except for individually owned pieces of allotted land near Fort Sill, Oklahoma, in what was called the Kiowa Comanche Apache Reservation (KCA). The KCA, established circa 1868 prior to Oklahoma becoming a state, was a treaty arrangement negotiated with Natives to restrict them to small portions of their land, thereby opening the rest to settlement by Americans.

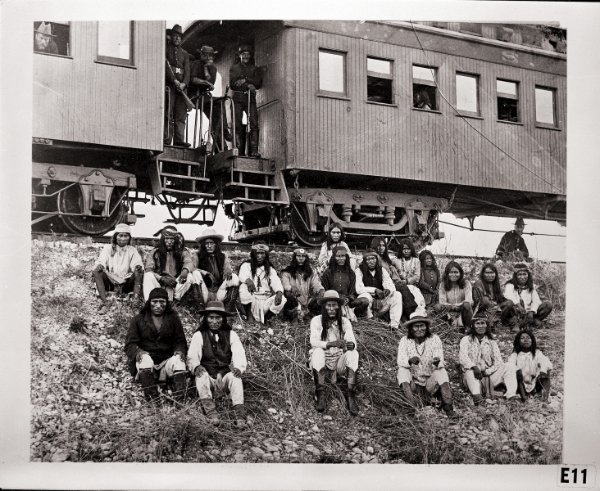

The Fort Sill Apache Tribe is a single Nation comprising several component bands, the largest of which are the Chiricahua and Warm Springs. In the late 1800s the members of these tribes—by then around five hundred men, women, and children—were made prisoners of war and exiled to Florida and later Alabama. In 1894 they were relocated to Oklahoma and held as prisoners of war at Fort Sill. In 1913, six years after Oklahoma became a state and one year after New Mexico gained statehood, the Fort Sill Tribe was told its individual tribal land allotments on the KCA were expiring. Tribal members were offered release from imprisonment in exchange for joining the Mescalero Apache Tribe on its reservation in New Mexico. One hundred eighty Apache prisoners of war moved to New Mexico and were adopted into the Mescalero Apache Tribe. Eighty-one of these prisoners did not want to integrate into another Tribe’s language and culture on homelands that were not their own. They remained in Oklahoma, hoping for land that had been promised to them by the U.S. government—or better yet, land in their true home territory in southwestern New Mexico.

In 1944, the Fort Sill Apache Tribe filed a federal land claim that was settled by the Indian Claims Commission in 1966. Ten years later, on August 16, 1976, the Fort Sill Apache Tribe was reorganized under a constitution approved by Congress. Subsequently, the Tribe was able to start acquiring small pieces of land in its home territory and have them placed in trust status.

Just before leaving office, former Fort Sill-Chiricahua-Warm Springs Apache Chairman Jeff Houser began to look at expanding the Tribe’s thirty-acre parcel of land near Deming in 2012. Because it was excluded from consultation as a New Mexico Tribe, the Fort Sill Apache sued former New Mexico Governor Susana Martinez to be included in the State Tribal Collaboration Act. Ten years later, in 2022, the Tribe made arrangements with the state to exchange 1.3 acres of valuable land it had purchased in Albuquerque for approximately 1,880 acres adjacent to its original thirty acres outside of Deming. Each property had an appraised market value of approximately $429,000.00. The Tribe’s revenue comes, in part, from its gas stations and a small casino in Oklahoma.

It’s a matter of perspective how long it took the Fort Sill Apache to get this small parcel of 1,800 acres of land back. On the one hand, it can be argued that it took the Tribe nearly two hundred years too long. From another point of view, it was a quick turnaround of ten years from former New Mexico Land Commissioner Ray Powell and Houser discussing the possibility to Garcia Richard finalizing the transaction.

The Fort Sill Apache encountered pushback from both the State of New Mexico and some of their Apache relatives when they began asserting their right to hunt on their own land—

a right afforded to every other tribe in the state. This right was assured by a federal judge in a recent case.

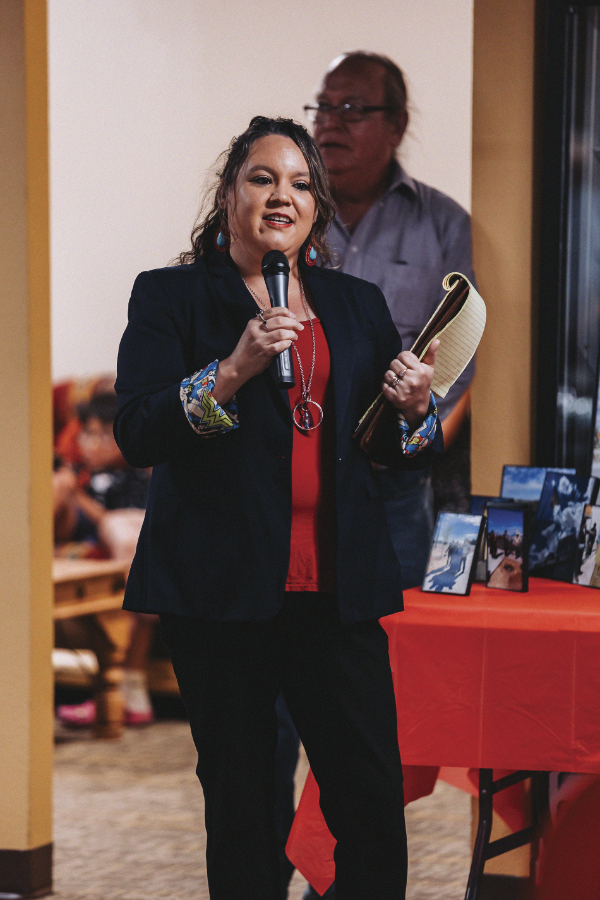

The dispute has not deterred newly elected Fort Sill Apache Chairwoman Jennifer Heminokeky. She has moved forward with what her predecessors started, and she’s determined to see it through. She has joined forces with Luna County Manager Chris Brice to bring more services and infrastructure to the Deming area in a joint effort to create jobs and community for their respective citizens. This kind of collaboration is the result of what centuries ago may have been an impossibility.

It’s almost impossible to tell anyone what is and is not worth any dollar amount. Armijo, Heminokeky, Brice, and Garcia Richard are all community- and service-driven people. They are doing what is best for their citizens. They are striving to be good neighbors, building communities, bridges, and pathways toward growth. This growth is physical as well as spiritual and cultural. They are sharing resources and space and ensuring their communities have access to resources. This cooperation to me speaks of the kind of reparations that go unnoticed but are astoundingly necessary for healing. I believe we are all reconnecting and returning home to a specific place and along with that, a sense of identity.

Returning Home

Forced removal—like many other violent acts—creates wounds that require care and the intention of repairing and replacing what was taken away. In the case of stolen land or artifacts, repatriation to the original caretaker is of utmost necessity.

The U.S. has been gaslighting Indigenous people since its “discovery.” In trying to understand it from my cultural teachings—that there is no “good” or “bad”—I want to know what caused people to steal other peoples’ living spaces. Why are we not able to share? When did we concede permission to buy and sell land where people had already established lives?

These are not easy questions, especially in the aftermath of so much violence. Our cultures and identities are marked by a resilience that existed prior to being tested. The strength of our spirit sometimes bent beyond our own recognition.

I spoke with one of Fort Sill Apache’s well-known elders and artists, Bob Haozous, about returning home. He, like I, was born outside of the reservation. He considers himself an outsider. But he has made peace with this fact by connecting with Indigenous relatives in other tribes: gaining wisdom in their teachings, connecting with his culture through art, and realizing that what we perceive to have lost, was never really taken away. I understand this concept as I have worked for the last seven years healing from the generational trauma inflicted on my ancestors through their forced removal.

For those of us who grew up outside our ancestral lands, there’s a joyful remembrance in our souls and a mournful ache in our hearts. We feel both ease in our spirits and the painful dissonance of having missed so much of our lives. The collective loss spans generations that we can never fully recover. Something is always missing. That includes the violent way our ancestors and lands were taken from us. Haozous tells the stories of what he saw growing up:

Busloads of children being taken away from their parents. When the white people came, what do they do? The first thing they do is they took away our children. They took away everything … no more language, no more songs, no more ceremonies … Just get rid of the Indian. Our land, our culture, our kids, our future, our identities—gone in a matter of seconds.

What is the value of getting that back? What price do you put on that? How much do you pay to get back not only pieces of your identity but the cumulative identities of generations?

According to a story that Haozous retells, when he asked his friend Frank how we Natives go about getting back stolen land, Frank’s reply—ironically metaphorical—on the surface seems almost passive, but in reality, challenges the colonized concept of ownership. Frank said we must understand that what we thought was missing was never really taken away. Ownership may pass hands and generations but our relationship with our land will never be taken away. The land knows who her stewards are. And the land knows who takes care of her and her inhabitants.

—

DezBaa´ is a Diné multi-hyphenate artist: an essayist, screenwriter, actor, filmmaker; mind-body healing facilitator; and single parent. She is a “Norteña,” born in Santa Fe and raised in Northern New Mexico. DezBaa´ is a graduate of Northern New Mexico College, Amherst College, and the Institute of American Indian Arts, with a certificate and bachelor’s and master’s degrees in Massage Therapy, Geology, Screenwriting and Creative Nonfiction, respectively. She’s still figuring out what she wants to be when she grows up.