Hands, Heart, Land, Table

New Mexico Culinary Traditions That Invite Us In

By Mi’Jan Celie Tho-Biaz

When we arrive at the table, we witness an assortment of heads intermittently lowered in praise-filled bites, not prayer, trying to draw the meal out as long as possible. No food grows cold or is left over, which is the ultimate compliment to the chef.

What is New Mexican-based art, if not our foods?

The arts all carry the opportunity to permeate our minds and hearts, traveling different routes to our scatterplot of available senses.

Depending on the bass, volume, and type, music touches our ears, prompting our heads to nod, hands to tap, and feet to follow.

Performing and visual arts are a bit more distant, only able to be perceived by our eyes or ears or rhythmically through floorboards at a length of space that supports the interplay between artist and audience. Images, movement, and action allow opportunities for these art forms to be physically touched and felt.

But culinary arts in New Mexico? It is the rare art form that combines each of our senses.

Almost like a mathematical order of sense-bearing operations, New Mexican culinary dishes travel very close to the nose so that we can make our final approval–to inhale what our eyes have already taken in. We usually have a funny way of smell-seeing our foods because many delicious dishes (such as fry bread and tamales) can be held in our hands.

Culinary arts are ultimately reliant on our mouths; however, it is the art form that is the most intimate, literally ingested by our bodies to sustain our physical life, which means that it carries the highest likelihood of a daily artistic practice. My favorite way of engaging in the practice is beside my master chef friends. They cook and later clean, while I prep and dry dishes. The kitchen is transformed daily into the place where we trade jokes, listen to music, and guard culinary and life secrets around a festive table built for loving our collection of friends, chosen family, collaborators, and sweethearts.

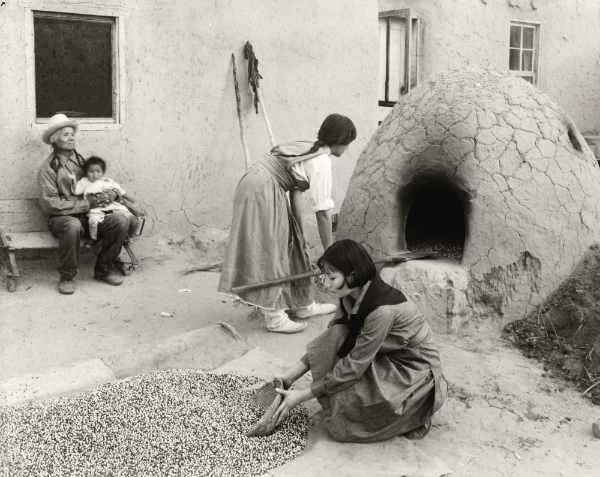

While I could join many others who have written love letters about everything uniquely delicious to New Mexican cuisine, as well as our different fusion variants, it is the communal eating experiences where we truly shine. Like other states, we have the usual roundup, including movie theater dining, where you can sit in front of the big screen and join a full theater of other diners facing cinematic action. There’s also food truck culture that offers roadside eating for you and your chosen community. And we have plentiful bars where diners can order a meal and a drink, choosing to speak with the bartender and anyone else who is agreeable and seated on your left or right. While I believe that our kindest culinary gesture happens periodically during the Pueblo Feast days, we can routinely find generosity, connection, and care through our community tables.

This past spring I went to lunch with a friend in Santa Fe. The restaurant was packed, and we were both pressed for time, which made the ten-person community table of travelers and locals our quickest option. While most of the table’s newcomers could never figure out whose menu was supposed to be whose, there was zero grumbling because we were hungry and most of us only needed to see one thing listed: breakfast burrito, with its constant companion of red, green, or “Christmas” chile.

The community table’s composition seemingly mirrored the kaleidoscope mix of the smothered breakfast burrito flavors, and the dedicated ensemble of hands that create and transport each aspect of the dish to the table: acequia waterway protectors, agricultural growers, farmers and ranchers, chefs, and restaurant waitstaff.

It strikes me as interesting how people from different geographies and developed palates can encounter the intersection of New Mexican culinary arts at the communal table, as if the table and food are in a friendly competition to see which can elicit more of a spirit of connection and nourishment. I quietly wonder about the last time that I encountered a compelling art form with an invitation to similarly experience mandatory nourishment, while surrounded by a small group of other people having the same experience, facing and talking with each other.

While I do not want this love letter to misrepresent communal tables as utopias of the culinary art world, I am fairly certain that it is a subtle New Mexican approach to our food and the unique settings that serve as connectors that transcend singular senses, bundling the entirety into a more dynamic whole. After all, our foodways tell the story of our longstanding New Mexican traditions that are tied to complex histories as we nourish our yet-to-be-told futures.

I wonder if my constellation of feelings about New Mexico’s unique food traditions is a requirement for our food’s soul not being defined by rich taste or spices alone. One of the hallmarks of soul foods around the world is how they hook you from the first bite, demanding heads, hearts, and bellies to feel an undeniable kinship to the hands, hearts, and land that made it so.

We may arrive at the communal table alone or joined by loved ones. In either case, we will likely feel invited and welcome. The day could be a special occasion or part of our routine needs. But odds are high that each person will have two points of overlap–the culinary art, and the artful act of being woven together with other eaters–neither fitting neatly into one box, alone.

—

Mi’Jan Celie Tho-Biaz, Ed.D. is a Kennedy Center Citizen Artist who moves between realms of oral history, art, ritual, and civic engagement. She is a 2024 National Council on Public History Honoree for her oral history and public art work, an inaugural New America Us@250 Fellow, as well as a 2023–2024 Andrew Mellon Foundation Fellow at the Huntington Library where she is researching Octavia E. Butler’s archives.