Monuments of Mutuality

The Legacy of World War II Trauma in Santa Fe

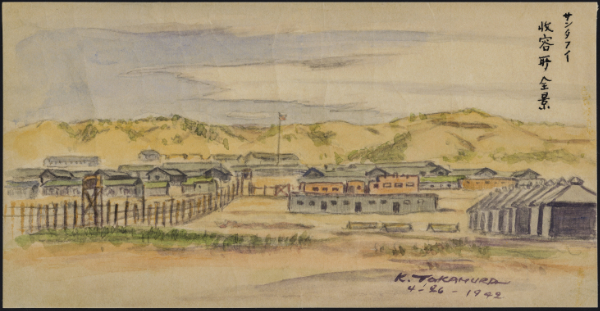

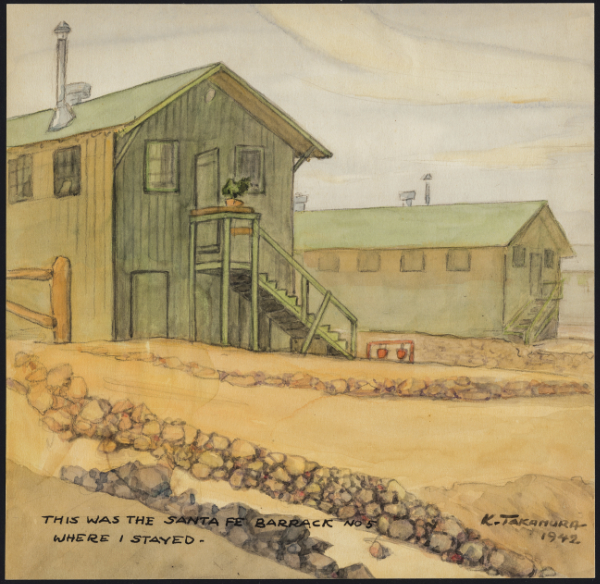

Santa Fe Internment Camp, New Mexico 1942-1946. U.S. Department

of Justice photograph, PAMU.233.2. Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors

Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), Neg. No. HP.2014.14.2948

Santa Fe Internment Camp, New Mexico 1942-1946. U.S. Department

of Justice photograph, PAMU.233.2. Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors

Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), Neg. No. HP.2014.14.2948

By Almah LaVon Rice

The documentary begins with a close-up view of an apparent snowscape. The camera eye sweeps slowly across what must be packed snow, glittering in the sunlight of the Southwest. Text surfaces on the screen, revealing haunting lines that confirm what we must be seeing:

In the field of white snow

I starve for the love

of my own people.

Yuki Shiroki

No Ni Nikushin No

Ai Ni Ue.

—Itaru Ina

But look closer: Maybe the snow is sand, perhaps a nose-close view of the gypsum at White Sands National Park? No, it is not snow. Nor is it sand. Nor salt. Via a deliberately paced reveal, the Community in Conflict: The Santa Fe Internment Camp Marker documentary makes clear that we are witnessing something far weightier—a six-ton boulder embedded with a bronze plaque proclaiming where 4,555 men of Japanese ancestry were unjustly incarcerated during World War II. This mound of stone from Arizona is thus stamped with a nation’s shame.

But the marker almost didn’t happen. The most vocal objectors were WWII veterans and their allies in Santa Fe. Specifically, some of these veterans were survivors of the Bataan Death March—in which the Japanese Imperial Army forced thousands of captured Filipino and American soldiers on a hellish sixty-five-mile trek to prison camps in the Philippines. These twin tributaries of wartime trauma—in the prison camps of New Mexico and the Philippines

—converged in Santa Fe in the late 1990s. The tale of two traumas is the center of Community in Conflict, directed by Claudia Katayanagi, produced by Nikki Nojima Louis.

Genesis of Anti-Japanese Sentiment

December 7, 1941, according to the famous speech by then-

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “is a date which will live in infamy.” On that day, the Empire of Japan unleashed a surprise military attack on Pearl Harbor, a U.S. naval base near Honolulu. The U.S. Pacific Fleet was pulverized, and more than 2,400 Americans were killed. On December 8, the U.S. declared war on Imperial Japan, and three days later, the U.S. officially entered WWII.

The fallout began immediately for people of Japanese ancestry in the Americas, from California to Peru. Less than a full day after the Pearl Harbor attack, the FBI started rounding up Issei, or first-generation Japanese immigrants. Xenophobic furor swept across the country—especially on the West Coast, which was partitioned into military zones. On February 19, 1942, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing the removal of select groups of civilians from said military zones due to espionage-related hysteria. According to the Densho Encyclopedia, “Perhaps [influenced by] racialized thinking, [Roosevelt] was quick to believe unfounded reports of Japanese American espionage and was largely indifferent to the human cost of the policy.” While the language of the order did not single out Issei, or Nisei (U.S. citizens with Japanese immigrant parents), its implementation overwhelmingly targeted these populations.

On March 18, 1942, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9102, which established the War Relocation Authority (WRA)—a federal agency that presided over the purging of more than 125,000 persons of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. More than two-thirds of those removed and imprisoned were native-born U.S. citizens; those who were not U.S. citizens could not become so, thanks to the Naturalization Act of 1790 and its subsequent amendments. (The restriction against all people of Asian ancestry was not officially lifted until the enactment of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952. Even then, provisos were included that favored European immigration over Asian immigration.)

Despite the state’s reputation as a haven for racial tolerance, U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) agencies, including the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), facilitated the location and administration of four American concentration camps—

euphemistically known as “relocation centers,” “assembly centers,” and “internment camps”—in New Mexico. The confinement sites in New Mexico were established in Santa Fe, Lordsburg, Fort Stanton, and Old Raton Ranch (a.k.a. “Baca Camp”). While the WRA managed most of the prison camps in the country, the DOJ and INS oversaw the New Mexico sites because incarcerees were deemed “enemy aliens” for reasons as innocuous as being born in Japan or being respected community leaders.

But a warm, partially cloudy day in Oahu eight decades ago did not mark the start of anti-Japanese sentiment in the U.S. or the Land of Enchantment. What is now known as the Anti-Japanese Exclusion Movement started gaining ground in the late nineteenth century. It was fueled by the racist concept “Yellow Peril,” which frames Asian people as the invading “other,” posing a threat to white Western civilization. Anti-Japanese exclusionists exploited the outcome of the Russo-Japanese War—the first time in modernity that an Asian power defeated a European one—to argue that Japanese descendants in the U.S. were existentially dangerous. The Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907–1908 as well as the Ladies’ Agreement of 1921 were both forged to hinder Japanese immigration to the States. Spearheaded by California, many primarily western states established alien land laws to block Issei from land ownership. New Mexico jumped on the nativist bandwagon in 1921 with a constitutional amendment barring property ownership for “aliens ineligible to citizenship”—despite the fact that people with Japanese ancestry in the state numbered fewer than three hundred. The New Mexico legislature did not drop this amendment until 2006.

While the DOJ and INS were imprisoning successive waves of Issei and Nisei men in Santa Fe, another tragedy was unfolding almost eight thousand miles away. The New Mexico Brigade had been deployed to defend the Bataan Peninsula in 1941. The Japanese military captured the peninsula in April 1942, eventually rendering the New Mexicans prisoners of war along with Filipino soldiers. American and Filipino troops were forced into what is now known as the Bataan Death March and were subjected to starvation, dehydration, medical neglect, torture, and wanton execution. The troops that survived the march were imprisoned at Camp O’Donnell in Luzon, where thousands of POWs continued to perish. U.S. and Filipino forces wrested control of the camp on January 30, 1945. The New Mexico Brigade—also known as the New Mexico National Guard’s 200th and 515th Coast Artillery—comprised 1,816 men. But 826 of them never saw home again. Physical and psychic scars persisted for those who did.

When the Political is Personal

The genesis of Community in Conflict is grounded in stories unburied, silences broken. “For over fifty years, our community was silent for many of the reasons—for security, protection, so your family isn’t deported, and all the reasons that people have for protecting their secrets,” Louis explains. “But I just found it extraordinary, because I’m part of that generation. My mother was very much a part of that generation of silence.” Louis was born in Seattle and raised in Chicago, and she and her mother were imprisoned at the Puyallup Fairgrounds in Washington State as well as the Minidoka Camp in the remote Idaho desert. Louis’s fourth birthday party was crashed by the FBI, who took her newspaper editor father, the Tokyo-born Shoichi Nojima, to the camp in Lordsburg and then Santa Fe. The aftermath of these injustices included Louis’s own “internalized racism and denial,” as she says.

Louis is now based in Albuquerque, which seems like full-circle cadence considering her little-girl visions of New Mexico. While imprisoned in Minidoka, Idaho, she would receive packages from her father who was imprisoned in Santa Fe. The packages, stamped “Enemy Alien Mail,” were filled with beaded jewelry, wooden toys, and Pueblo pottery. The parcels testified to anguish, injustice, state-sanctioned theft, family separation, and more—as well as a father’s untrammeled love for his daughter. They also cemented New Mexico as “a magical place” in Louis’s young imagination.

Katayanagi, who is based in the San Francisco Bay Area, is

steeped in a similar legacy as a Nikkei Yonsei, or fourth-generation Japanese-American. “I realized I’ve denied my Japanese heritage for a long time,” she writes on the A Bitter Legacy website. “By exploring this Nikkei history in these American Concentration Camps, I began to fully appreciate my cultural heritage and all that pain and indignation all the Nikkei families have suffered.” The UC Berkeley graduate adds, “All of my relatives were in these concentration camps during the war,” including her parents and even a cousin who was born in the Topaz, Utah camp.

It is no wonder, then, that the life work of Louis and Katayanagi is concerned with the politics of memory and the personal, collective, and ancestral implications of the archive. Louis is an accomplished theater artist with a PhD in creative writing from Florida State University. She is also the artistic director of the JACL Players, the theater group of the New Mexico Japanese American Citizens League. In addition to her Pacific Northwest work, the plays she has written, directed, and toured in New Mexico include Asian American Legacy Stories;Lordsburg Diary; Citizen Min in New Mexico; From Days of Infamy to Days of Remembrance;and Nisei, the Greatest Generation: Soldiers, Protesters & Prisoners. Her plays on the prison camps of New Mexico include Confinement in the Land of Enchantment; Barbed Wire and Cactus;and Courage and Compassion: Stories from Inside

and Outside the Barbed Wire of the Internment Camps of New Mexico.

Katayanagi boasts decades of film experience, including directing, producing, and location sound mixing/recording. Her award-winning film, A Bitter Legacy, explored Citizen Isolation Centers, which isolated “troublemakers” from the general population of incarcerees. (Being educated in Japan could be enough to earn the label “dissident.”) As she points out, these illegal centers are now viewed as the antecedents of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo. Community In Conflict is the second film of the trilogy that began with A Bitter Legacy; she is currently at work on Exiled,the final film in the series. Exiled focuses on alien detention camps and also plumbs the history of Latin American countries turning their citizens of Japanese descent over to the U.S. government.

Katayanagi’s unflinching gaze upon these brutal histories sparked Louis’s desire to collaborate. Louis explains, “This collaboration started with my interest in A Bitter Legacy. I think of Claudia as a photojournalist, an investigative reporter—because she doesn’t make nostalgic films about our time in camp. I mean, many of those films are really, truly beautiful and lyrical. But you know, she goes to these places where she is not wanted.”

When WWII Traumas Collide

Community in Conflict goes to places where truth-tellers and anti-revisionists must go. A spare, brooding piano score accompanies the film from the start, as historian and former New Mexico History Museum Director Thomas Chávez recalls holes in the historical record. He says, “The state history museum has a state history library and photographic archive. We have historians come in there to research and we were periodically getting questions about the internment camp, and we had nothing in our archives or library about that.” Chávez later continues, “I wrote an article about the existence of this camp, and I just said, ‘Wouldn’t it be interesting if we could put a marker there?’” His 1997 guest editorial in The Santa Fe New Mexican led to the creation of the Santa Fe Internment Camp Marker Committee. Patti Bushee, Santa Fe City Councilor at the time, concurs: “I was enthusiastic from the get-go. This was a piece of history that deserved everybody knowing about it. It deserved recognition. When I presented the initial resolution, it wasn’t costing the city a dime.” But the resulting blowback from some community members was emotionally expensive—and explosive.

Some survivors of the Bataan Death March and their supporters made a misguided equivalence between their Japanese torturers in the Philippines and the incarcerees at the Santa Fe camp.

“They were all confused thinking that this was a prisoner of war camp … a lot of people [were] just uneducated or they just don’t know there was an internment camp,” states Katayanagi. The misinformation and attendant rancor called for an intervention. “I was called in to the city manager who said, ‘We need to get community dialogue. We need to resolve this. We need to see where citizens are at, and we need to decide whether we’re going to do this or not,’” remembers Gerard Martínez y Valencia, then-director of the Office of Intercultural Affairs for the City of Santa Fe, who teamed up with the Institute of Intercultural Community Leadership of Santa Fe Community College. “We designed a facilitation process for this and then took off with it.”

Three community meetings were convened, employing a roundtable format. Hearing stories directly from the incarcerees or their family members softened some of the anti-marker contingent. One testimony came from Joe Ando, a retired Air Force colonel who was incarcerated at Arizona’s Gila River camp; his father was confined in the Santa Fe camp. He says, “I am a veteran and I speak to a lot of veterans, and I have been asked to speak to Bataan veterans’ groups. During the question-and-answer sessions I get some serious, hard questions thrown at my race. Anger comes at me. I throw words back; I don’t throw anger back. Surprisingly, I make friends that way.”

As Chávez points out, some of the veterans were not aware that the imprisoned were citizens or prevented from becoming citizens. Many did not know that some of their brothers in battle were of Japanese descent. In fact, the most decorated unit in U.S. military history was the 442nd Infantry Regiment, the majority of which were Nisei soldiers who fought in WWII. “The card we played at the end, the one we were holding was: and they served in WWII. That I think is the one that tipped the balance,” Chávez concludes.

Even so, a retired lieutenant colonel vowed to urinate on the marker if it ever went up. Another opponent threatened to defecate on it. Ethnic slurs were spewed. As noted in Kellie Nicholas’s article, “Santa Fe Marker Project and Controversy,” in the book, Confinement in the Land of Enchantment: “One observer remarked to the local media on the racism he detected, stating, ‘You would have thought the war was still going on.’” It was such a powder keg situation that the split Santa Fe City Council delayed voting on the marker. The vote was finally held on October 27, 1999—with police on hand because of the volatility. In fact, the police chief stepped in when one of the marker opponents started threatening physical violence.

This is the point in the film where Louis and Katayanagi make a particularly compelling artistic decision. Constraint fueled creativity: video of this charged moment in Santa Fe history could not be located, so, as Louis says, “You have to make lemonade out of lemons.” Katayanagi adds, “In the council meeting where they had the actual vote … there was a story that the local PBS or the local public access TV station had filmed this meeting and apparently it was very dramatic. It was … people were getting up and yelling and screaming and almost getting into fistfights. … And I spent many, many hours looking for this footage. I contacted the public access [channels], I contacted the museum, I contacted City Hall.” She kept hearing about a possible videotape in an attic. She asked everyone,it seemed. But finally, the documentarian had to cease her search. “I accepted the fact that I wasn’t going to get this original footage,” recalls Katayanagi. “So, I went to Nikki [and said] ‘Let’s do a reenactment.’”

And what an inspired decision that was. The powerful dramatization was based on minutes of the meeting; Louis adapted the minutes into a script. Actors perform in the black-and-white reenactment, which crackles with opposing viewpoints; Louis plays Councilor Carol Robertson Lopez, who appears in one of Community in Conflict’s interviews. Stormy facial expressions and vexed body language further help transport viewers to the crowded city council chambers of that day. Mayor Larry A. Delgado ended up having to break the tie with a “yes” to the marker. One of the yelled-out reactions, from former City Councilor Clarence Lithgow? Your vote has kicked the Bataan veterans right in the teeth.

But the other resolution that passed that day was for establishing a memorial for those who did not survive Bataan. This memorial was one of the fruits of the facilitated intercultural dialogues. Martínez y Valencia recalls how his group’s task was to excavate “what it is that [the Bataan veterans] were really upset about.” And what did the group unearth? “Well, the bottom line with what we heard from the veterans was, ‘We have not been honored with anything,’” he says. From their perspective, the honoring that they had received was negligible. Their requests for a memorial had gone rebuffed for decades. So, the group decided that the marker and the monument had to be realized. “The whole group agreed they have to be side-by-side,” notes Martínez y Valencia. “Both groups want to be remembered. They want to be recognized. They don’t want to be abandoned again. … [B]oth of those groups were abandoned by their country in different ways,” says Rod Ventura, former member of the Bataan-Corregidor Memorial Foundation. “They all share something, and that’s trauma.”

Almost twenty-five years after the contentious city council vote, there are some indications that more Santa Feans are willing to look at and learn from the past—even the most painful chapters. “I think there is a hunger to learn,” asserts Katayanagi. “People go, ‘I didn’t even know there was an internment camp in Santa Fe … and how come I don’t know this?’” Louis acknowledges that the current state of the conversation is complicated and dynamic, running the gamut from “healing, forgiveness, denial, and a refusal to admit that it ever happened.” She continues, “There are deniers of American concentration camps.”

The imperfect resolution is illustrated in the name of the marker itself. “The veteran community said, ‘You can’t call it a monument, you can call it a marker.’ So that’s why the town’s sign says it was ‘Santa Fe Internment Camp Marker.’ But internally, I just call it a monument.” Katayanagi prefers calling it a “memorial,” invoking the Nikkei pilgrimages to confinement sites. As Louis explains, “Claudia talks about the insult for calling this a marker, because the marker is a little sign that tells you to go this way to wherever your destination is—not to dignify it by calling it a monument or a memorial.” In contrast, pilgrims to the camp—many of whom are descendants of the men imprisoned there—perform ceremonies to re-sacralize what is now the Frank Ortiz Dog Park.

Katayanagi references the opening haiku by Itaru Ina, a survivor of several prison camps throughout the country: “Yes, we all want the love of our own community … at the same time, we want to share.” She maintains a tradition of inviting all her friends to her Japanese New Year celebrations, complete with “food, ritual, and cultural activities.” That invitation reflects her view that the table of this nation is large enough to accommodate all of us. She adds, “And I think, in a way, what my film is showing is that there is a way to dialogue.”

—

Community in Conflict: The Santa Fe Internment Camp Marker will be screened as a part of the Museum of International Folk Art’s exhibition, Between the Lines: Prison Art & Advocacy. To learn more, visit internationalfolkart.org/. Subsequent screenings are planned throughout 2024 and can be found on the New Mexico History Museum’s events page at nmhistorymuseum.org/programs/events/.

A former resident of New Mexico, Almah LaVon Rice is a Pittsburgh-based writer at work on their first book. You can find more of their writing at AlmahLaVonRice.com.