Filling Gaps in the Archive:

The Complexity of Queer Art, Community, and the Historical Record in <i> Out West</i>

Laura Gilpin (1891-1979), Agnes Sims, 1946. Gelatin silver print. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth,

Texas, Bequest of the artist; P1979.130.955. © 1979 Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

Laura Gilpin (1891-1979), Agnes Sims, 1946. Gelatin silver print. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth,

Texas, Bequest of the artist; P1979.130.955. © 1979 Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

By Robin Babb

At the entrance to the gallery, a quote on the wall provides context and raison d’être for the Out West exhibition. It’s from Santa Fe author Walter Cooper’s recent book Unbuttoned: Gay Life in the Santa Fe Art Scene:

So much of our queer history has been swept under the rug, it’s almost as if we never existed. People tend to underrate or ignore “the queer factor,” the enormous impact gay folk have made on New Mexico’s unique cultural life.

Open now through September 2, 2024, Out West: Gay and Lesbian Artists in the Southwest 1900–1969 at the New Mexico Museum of Art (NMMoA) in Santa Fe presents work by and about queer artists in New Mexico from the turn of the twentieth century until the cultural turning point of the Stonewall Riots in 1969. During this period, modernism was on the move, and many artists were responding to the trauma of two world wars, the increasing urbanization and industrialization of the country, and the burgeoning civil rights and women’s liberation movements. While several of the artworks in this exhibition were familiar to me, being cornerstones of a New Mexico canon—paintings from Marsden Hartley, for instance, as well as works from Agnes Sims, R. C. Gorman, and Russell Cheney—the context of these artists’ lives has often been overlooked. In Out West, these artists and many others are showcased through the lens of their shared identities.

This is not to say that there’s no precedent of showing the work of queer artists in the state. The show takes its title after an earlier exhibition in Santa Fe curated by artist Harmony Hammond. Hammond, who now lives in Galisteo, New Mexico, says the current Out West “builds upon and includes documentation of Out West, the 1999 exhibition of work by contemporary lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and Two-Spirited artists living and working in the Southwest, that I curated for Plan B Evolving Arts—as CCA [the Center for Contemporary Arts in Santa Fe] was then called. Or we might say it provides the missing history, underlying the impetus for Out West at Plan B. I chose the title to not only reference being out of the closet, but also to invoke the metaphor of the West—outlaw country, where there is space to be who you think you are or wish to be.”

Indeed, the exhibition at NMMoA plainly seeks to locate the reality of lesbian and gay lives that so often gets elided from the official record. That evidence of this reality is often hard to find is no surprise—few of the artworks in this collection feature explicitly lesbian or gay content, and very few of these artists were out in their lifetimes (at least not in a public way; many of them were out within their trusted communities). This is its main divergence from Hammond’s 1999 exhibition: post-Stonewall, queer themes began emerging much more directly in queer artists’ work, sometimes in pointed and political ways that responded to the civil rights movement or the AIDS epidemic.

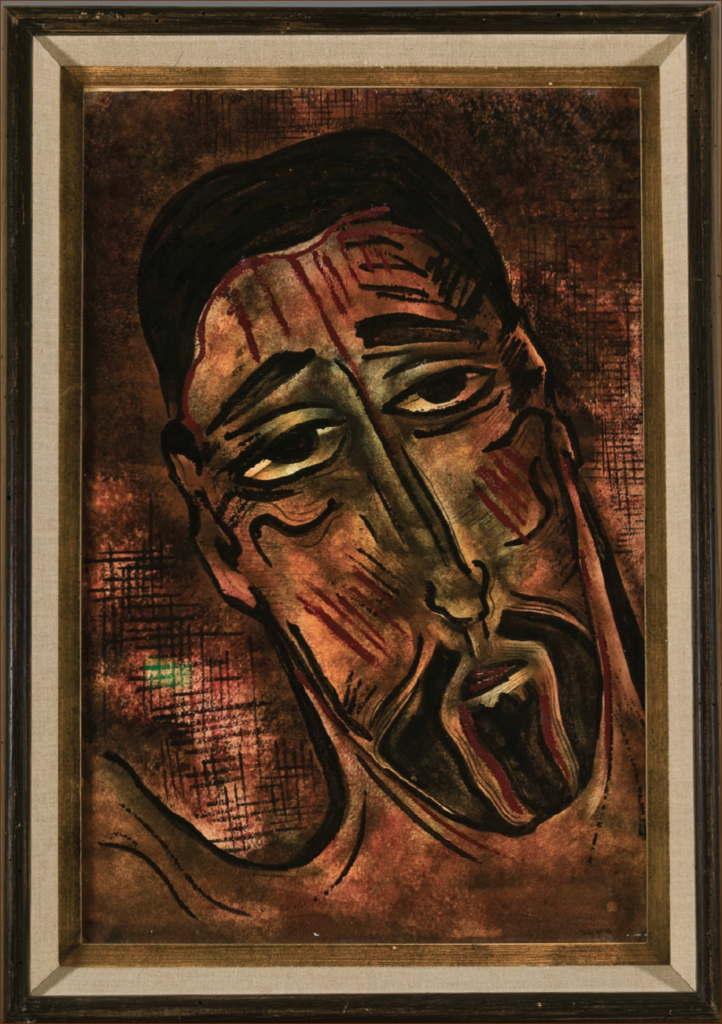

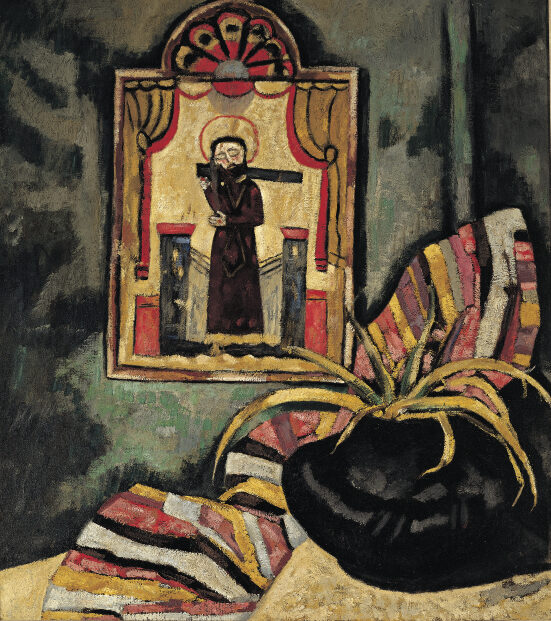

Despite the lack of what we might call queer content, there was certainly queer coding going on in much of this work—such as with Cady Wells’s 1939 painting, Head of Santo, which features the scarred and lacerated face of a Penitente in the symbolic role of Christ carrying the cross. Wells, Marsden Hartley, Russell Cheney, and other gay male painters in this exhibition often took up the Penitentes and their flagellation rituals as subject matter. It is possible that some of these artists inferred a homosocial understanding of the Penitentes, but as Christian Waguespack, head of curatorial affairs and curator of twentieth century art at NMMoA, wrote in his article “Perceptions of Passion” in the winter 2019 issue of El Palacio, “Due in part to a general lack of access […] of outsiders, accounts of Penitente activities and their representation in art often reflect popular stereotypes more than actual fact.”

In Manuel Acosta’s 1960 painting Youth, a portrait of a young Chicano man with delicate features and suggestively parted lips, this coding is even clearer. Within the permissiveness of artistic license, many of these artists found subtle ways to say the unsayable, to hint at sublimated identities and desires—but only to those who were paying close enough attention to see it.

In discussing why he chose “gay and lesbian” for the title of the exhibition instead of “queer,” Waguespack says, “‘Queer’ wasn’t really in their lexicon. The way that I use and understand ‘queer,’ I would want to open up the context a lot more to other gendered existences and ways of being, but I didn’t have the artwork to back that up.”

Waguespack faces a problem familiar to anyone attempting an honest study of queer history. Queer people have always existed, but up until very recent history, people did not use the word “queer” for themselves. Their understandings of themselves, their sexualities and gender identities, were as bound by the time they lived in as ours are today.

In much the same way that the term “queer” arose from its status as slur into an embraced umbrella term for a diversity of identities, the relatively modern, English-language term “Two-Spirit” is a blanket term for nonheteronormative or nonbinary Indigenous identities. Identities outside of the male-female binary have long been acknowledged and even celebrated within many Indigenous cultures, but centuries of assimilationist practices succeeded in driving many of those traditions underground. From the 1920s to 1940s, while Taos and Santa Fe were providing community and (relative) safe haven to white gay and lesbian people from outside the state, the U.S. government and Christian missionaries were condemning traditional Pueblo cultural and religious ceremonies; stealing children from Pueblo, Diné, and other tribal families; and enforcing assimilation to white mainstream culture—including assimilation to conservative Western ideas of heteronormativity and the gender binary. Contemporary acknowledgement of these identities and histories help revitalize efforts to resist colonization and assimilation practices still happening today.

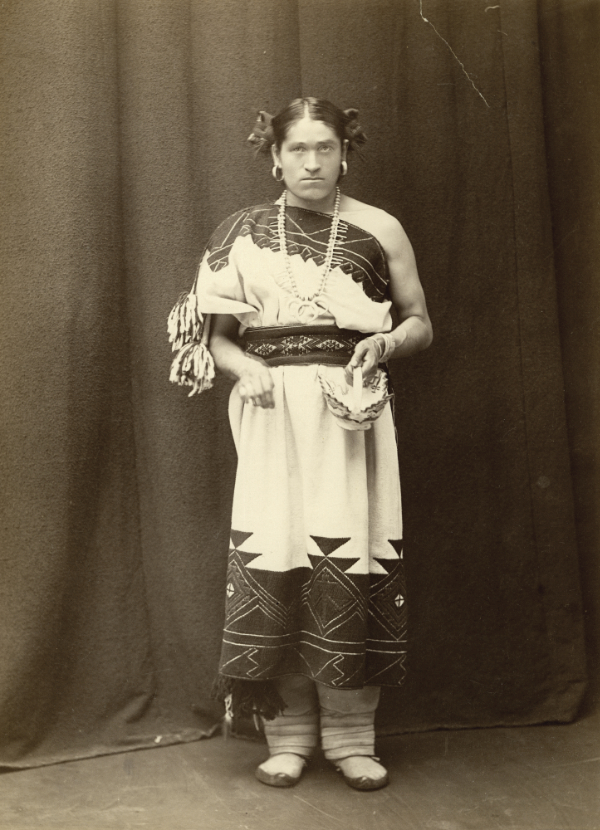

One alcove in Out West includes two photos of the late Zuni artist We:wa (1849–1896): a studio portrait and a photo of him weaving on the lawn of the Smithsonian, as part of a cultural demonstration he gave in the 1880s. According to Curtis Quam (Zuni), friends and family members largely used both feminine and masculine English pronouns for the late We:wa who was a Łamana, a kind of Two-Spirit tradition unique to Zuni Pueblo. Quam emphasizes, however, that his perspective is not necessarily representative of all Zuni perspectives on the late We:wa. The late We:wa was considered to have been born male, but often wore traditional Zuni women’s clothes and performed work that was typically performed by women—in Zuni, this meant pottery. Her designs in both weaving and pottery were considered expert in her time, and many artists—Zuni and otherwise—took inspiration from her work. Waguespack would have loved to include some artworks by the late We:wa in the exhibition, but the few extant works are all at the Smithsonian.

Another Native artist is depicted in the exhibition: In a smoky lithograph by R. C. Gorman titled Clah, a monolithic face gazes out in the foreground of a mesa. The face is that of Hastiin Klah (1867–1937), a renowned Diné weaver, sand painter, medicine man, and nádleehi. Nádleehi, which roughly means “one who has been changed” or “one who is constantly changing,” was a traditional designation for what non-Natives consider a third “gender” in Diné culture; typically, somebody who was born male but who dressed as and performed roles often ascribed to Diné women, like weaving (though there is some disagreement from the younger Diné generation about the translation of these roles). According to Diné educator and advocate charlie amáyá scott, Klah was believed to be intersex, and the rough English translation of “Hastiin” in English is “man.” As far as we know, Klah was referred to largely by masculine English pronouns during his life. Klah’s knowledge of traditional Diné medicinal practices was second to none; his weaving incorporated expertise of ancient patterns as well as a radical break from tradition; and his commitment to an ascetic, spiritual life was complete. His artistic and cultural legacy reigns titanic in the Native Southwest—he was a co-founder, along with Mary Cabot Wheelwright, of the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe.

Klah was deeply loved by white and Diné communities—but he was also controversial in his lifetime among the Diné. In the 1930s and 1940s, Klah worked with Wheelwright to record sacred Diné ceremonies, chants, and sand paintings—recordings that now reside in the collections of the Wheelwright Museum and in several publications of the time. He was one of the first Diné artists to translate the usually ephemeral and sacred sand paintings used in some rituals into weaving, thus making them permanent and accessible to the non-Diné public. In 1919, he also wove the first depiction of a Yeibichai healing ceremony and sold it to Ed Davies, a white trader in the Two Grey Hills area. To many Diné, then and now, these recordings are considered sacrilegious—hence, Klah’s work is not shown to the public.

Still, Waguespack wanted to include the late We:wa and Hastiin Klah in the conversation, even if in portraiture alone. “You can’t tell the story of queer people and gender non-conforming people in New Mexico without talking about We:wa,” he says.

Of the canonical New Mexican artists whose work is featured in the exhibition, only one of them is Indigenous—R. C. Gorman, the commercially successful Diné painter who was called the “Picasso of American Indian art” by the New York Times in 1973. Although Gorman was born in Chinle, Arizona, within the Navajo Nation, he made the rural-to-urban migration common to queer people of the time. Following his service in WWII, he lived in San Francisco between 1955 and 1968. It was during these years that he solidified his identity as both an artist and a gay man.

His early paintings, most of which focus on Diné cultural practices and largely feature Diné women wrapped in brightly colored clothing, became something of a recognizable southwestern aesthetic of the era that was copied by dozens of artists, mostly white, to capitalize on the region’s growing art world cachet. His 1969 painting Night of the Yei very much falls into this period of his work and features several stylized yeis—spiritual beings in Diné culture that were associated with blessing and healing rituals.

Gorman also opened the first Native-owned art gallery in the country, which is still open in Santa Fe and sells reproductions of Gorman’s work. I didn’t know before I saw this exhibition that he was gay—although he was very much out in his lifetime. As Waguespack says, Gorman was more than a little flamboyant, both about his sexuality and his success: “He was taking private jets, buying everybody champagne…. He was very foppish and [threw lots of] parties, in the way that Andy Warhol was.”

Gorman moved to Taos in 1968, effectively leaving the queer capital of San Francisco and settling into a more rural existence. He was tracing a journey that few queer people and artists were making in that era—but certainly not none. Following statehood in 1912, New Mexico, with its wide-open spaces, cheap real estate, and general lack of supervision—governmental, familial, or otherwise—became a stage for many white artists, hippies, and other “unsavory” types. Many of those artists came and went with some regularity. Others stayed, put down roots, and created community. Then—and often now—queer migration flowed away from small towns and rural areas to big cities like New York and San Francisco where queer community was thriving. But Gorman and others like him instead looked to the Southwest, where insular artist colonies were already spawning in Taos and Santa Fe.

Perhaps it was a certain personality type that was attracted to the more arid and less cosmopolitan charms of New Mexico—those who wanted queer community, but also a degree of solitude; those who wanted to start a new life outside of the closet, but perhaps within a circle of trusted friends instead of being out to the wide world. Whatever it was that drew them here, it’s true that for painters like Agnes Sims and Marsden Hartley, photographers like Laura Gilpin and Anne Noggle, and writers like Witter Bynner and Lynn Riggs, Northern New Mexico became a kind of hub where queer artists settled to make art and make lives together.

“Northern New Mexico had a history of laissez-faire attitudes toward queerness that engendered the blossoming of a semi-open white queer creative culture,” writes Jordan Biro Walters in her book Wide-Open Desert: A Queer History of New Mexico. In relatively private spaces—like Mabel Dodge Luhan’s salon in Taos—as well as public—like the dining room at La Fonda Inn, where lesbians dressed in cowboy hats, dusters, and bandannas often dined together—these white, queer artists embodied a measure of freedom that was unique for the period. This freedom depended upon a strategy that literary scholar D. A. Miller terms the “open secret”: a sort of paradoxical accommodation to and acceptance of a heteronormative world for the sake of safety and appearances, one that also maintains subtle, embedded denials or resistances to that heteronormative world. In other words, to merely exist as a gay or lesbian person was an act of resistance—and the acts of community-building, homemaking with a same-sex partner, or cross-dressing in public were further expressions of resistance, whether or not they were explicitly labeled as such.

When visiting Out West, I couldn’t help but flinch at first glance of Agnes Sims’s Deer Dance statues—though beautifully made, the term “cultural appropriation” has rarely fit any artwork so well. Her roughly foot-high carved wooden figures are dressed in the regalia of a deer dance, a ceremony held by several Pueblos with ancient roots and private significance.

Sims was not the only white artist in this exhibition to have a fascination with Pueblo dances; the dances, in fact, were something of a flashpoint in New Mexico in the 1920s. Marsden Hartley attended several Pueblo dances and was inspired by them; he wrote essays and made paintings about them. His artworks, though, emphasized what Hartley saw as the sensual spectacle of the dances, and they certainly sidled into fetishization. As Biro Walters writes, “Gay men imagined Pueblo dances as a realm for fantasizing about cross-racial sexual liaisons and reformulating constructs of sexuality. Scholars have pointed out sexualized depictions by white women, but gay men participated as well.”

In the midst of these culture wars about Pueblo dances, Pueblo people became tired of having their longstanding cultural traditions and their sexual practices interpreted by anyone. As Biro Walters writes,

[T]he controversy demonstrates how whites publicly adopted a specific racial logic that intertwined race and sexuality, simultaneously pathologizing and celebrating Native sexuality. As art colonists perpetuated notions of Pueblo sexuality to empower their own sexual inclinations without consideration of the consequences for Pueblo Indians, Pueblos retreated to a culture of silence, refusing to speak to outsiders about sexual customs.

As previously noted, Wells, Cheney, and other gay artists also created work inspired by or appropriative of the Penitente Brotherhood. Like the Pueblo dancers, the Penitentes responded to these interpretations and to the public censure by withdrawing from public view and—perhaps worse—sometimes amending their rituals to be more palatable to a white audience with Victorian tastes.

It is this pattern of appropriation and interpretation, followed by an understandable closing of ranks, that largely defined relations between white artists and traditional Native and Hispano artists in New Mexico in the period examined by Out West. R. C. Gorman’s unique charisma, along with his background of serving alongside white soldiers in WWII and living for many years in the largely white city of San Francisco, allowed him to move through the cosmopolitan white art world with relative ease. However, many other Indigenous artists who lived and made art according to more traditional practices were often commodified by newcomers like Sims rather than treated as fellow artists, with whom an honest and equal exchange of ideas might be possible. This history is lamentable—but Out West does not seek to revise or reframe it.

“I don’t believe in saints,” Waguespack says when I ask him about Agnes Sims and her Deer Dance figures. “And I don’t believe in an approach to representing artists where we just put them on a pedestal and say everything that they made was golden. But at the same time, I think about putting what they were doing in a little bit of context—without giving them a free pass.”

For Sims, some of that context is this: In the 1930s and 1940s, Sims flaunted not only gender norms, but also expectations of monogamy, and even homonormativity. She sometimes identified as a lesbian and had several long-term romantic relationships with women—some of them happening concurrently—but there are records of her dalliances with men, too. She cross-dressed, drank scotch neat, and worked as a contractor in Santa Fe, renovating old houses. She bought land on Canyon Road and built a house for herself and one for her long-term partner, Mary Louise Aswell, so they could be close together but still each have their own space. In a moment that was largely defined by reactionary returns to conservative family values, Sims was looking forward, carving out a life that was aggressively her own.

As artists, all we can ever do is draw from the materials that were left to us by those who came before, try to understand them, and make something new with that understanding. When I moved to New Mexico from Oakland in 2015, I enacted a similar narrative as those earlier white queer artists who migrated here. I, too, was yearning for community, for rootedness, and for a place to belong.

I find a lot to relate to in the lives and art of the white queer artists represented in Out West: Agnes Sims, or Cady Wells, or Laura Gilpin. I relate most strongly to the writers whose portraits appear in the exhibition, like Witter Bynner. These artists and writers found inspiration in this place, and in each other. They recognized and loved the uniqueness of New Mexico, and when the moment demanded it, they came to its defense—most notably in helping to coordinate a public relations campaign to defeat the Bursum Bill that would have stripped Pueblos of their land and culture. When I read about Wells’s nuclear anxiety and bitterness towards Los Alamos, or about Alice Corbin Henderson’s impassioned defense of the Pueblos’ rights to continue holding public dances amid the pearl-clutching Pueblo dance controversy, I see people who loved this place and were trying to give back to it, trying to reciprocate for all they had taken. To us, as modern viewers of their art and their lives, these attempts appear fraught and problematic. As they should—we should always be interrogating our past, evolving our ideas, and trying to do better than those who came before us.

To me, the most compelling piece of the exhibition is the one at the end that hints at some of the queer history that’s been “swept under the rug,” in Walter Cooper’s words. It’s by Harmony Hammond. Originally made in 1997, it’s one of only two artworks that fall outside of the timeline defined by the exhibition’s title. It’s a multimedia piece depicting wrecked domesticity: floral-patterned linoleum that’s been chopped up and re-assembled in a hodgepodge manner, a wooden chair with a washbasin full of hay sitting on it, and broken blinds stained with red paint. On the valence above the half-open blinds, words in black read: What have you done with our desire?

The question comes from the French lesbian feminist writer Monique Wittig (1935–2003) and points to a history that has put narrow and un-nuanced boundaries on the ways we identify and understand ourselves. Perhaps it’s because Hammond’s work is among the more modern of the artworks in the exhibition and thus has some of the most recognizable queer content, or perhaps it’s because my own desires and identities mirror Hammond’s more closely than those of some of the other artists, but this piece is the one that gutted me. Hammond’s work, which often incorporates themes of domesticity and violence, is potent in its layered concealments and exposures. As anyone who’s intimately known that a home can also be a trap, the silences in our histories—and what doesn’t get said—is often as important as what does. As Hammond describes the piece: “The half-open blinds are in conversation with artists in the historical [1999] exhibition—many living proudly as homosexual or bisexual … others living half-open in same-sex relationships and lifestyles, but not naming it, and in not naming it, remaining apolitical.”

While I don’t believe queer artists, then or now, have a political responsibility to be out, I understand Hammond’s desire for nobody to feel they should have to live a life “half-open.” But, for their various reasons, many of these artists did live half-open lives—thus leaving us with a historical archive filled with gaps. How we choose to read this archive is up to us.

—

Robin Babb is an MFA student in creative nonfiction at the University of New Mexico. Her work has been published in Phoebe Journal, New Mexico Magazine, and Southwest Contemporary, and is forthcoming in the Kenyon Review. She was awarded a 2024 New Mexico Writers Annual Grant.