Acequias de Santa Fe:

Preserving What Remains

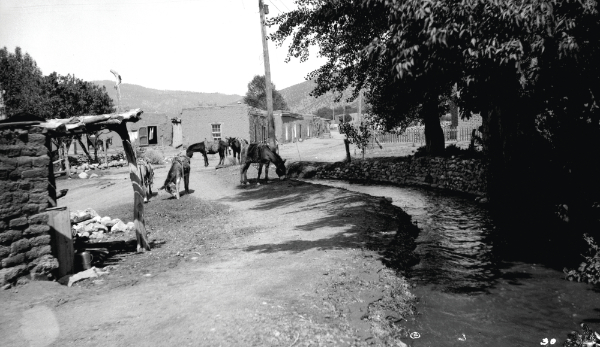

Harmon Parkhurst, Burros at Acequia Madre, Santa Fe, New Mexico,

ca. 1915. Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA),

011047.

Harmon Parkhurst, Burros at Acequia Madre, Santa Fe, New Mexico,

ca. 1915. Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA),

011047.

By Adele Oliveira

Last spring, after a wet winter yielded a decent snowpack, if you walked the narrow dirt path alongside the Acequia Madre in Santa Fe, between the ditch and the curb, the water gurgled companionably downstream beside you, following its centuries-old course, banks choked with green grass and apricot blossoms. When flowing at near-historic volumes, the Acequia Madre performs a kind of magic trick, becoming a portal to the past and a living cultural artifact, a physical example of what life used to look like in Santa Fe, and a potent reminder to preserve what remains.

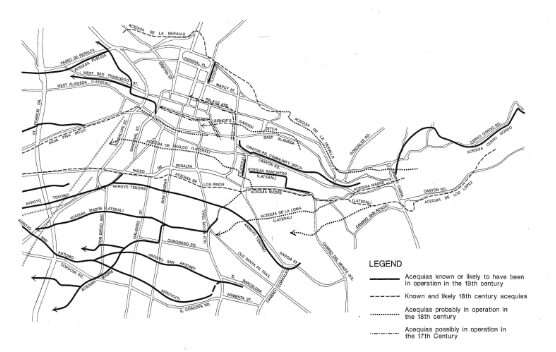

A century ago, Santa Fe was ribboned with acequias, nearly forty according to a 1919 survey, with hundreds more following the river downstream. Laterals and diversions watered fields and gardens, provided riparian habitat for wildlife, and shaded the town with what Enrique Lamadrid, historian, author, and professor emeritus of Spanish at UNM, calls “cultural greenery.” Today, just four acequias in the city limits still flow: Acequia Madre, Acequia de la Muralla, Acequia Cerro Gordo, and Acequia del Llano.

When community activist Rick Martinez was a boy in the 1960s growing up near the Acequia Madre, on days when it was flowing he and his friends would race paper boats down the ditch and wade barefoot in the water. He remembers an acequia that used to run parallel to the Acequia Madre behind his grandmother’s house on Canyon Road, long since dry. “Where the parking lot is now at the cathedral, that used to be the Bishop’s Garden,” Martinez says. “It was fed by acequias too and was a wetland. I saw it when I was a kid, but by the time I got to be twelve or fourteen, the area was covered up. [Developers] didn’t want to know more; they saw property being developed there.”

Acequias are complex community systems that are also beautifully simple: ancient, cross-cultural technology that offers clues about future survival in arid places as the planet warms and dry regions become drier. In the late sixteenth century when Spanish colonists first arrived in O’Ga P’Ogeh Owingeh, Indigenous people had been using the water from the Santa Fe River via diversion ditches and flood irrigation for centuries, farming crops like beans and corn, while the irrigation techniques that the Spanish brought to New Mexico originated with the Moors during the Middle Ages on the Arabian Peninsula. “Acequia” derives from the Arabic word “as-saqiya, which means “that which brings water.” The colonists’ survival was contingent on successful agriculture, and the Spanish augmented the existing ditch systems, digging canals (or forcing Pueblo residents to do it for them) that in some places remain essentially unaltered: Santa Fe’s Acequia Madre, dug in the early 1600s, is the “oldest remaining Spanish acequia in the southwest that can easily be traced today,” according to an Historic American Engineering report—though the Acequia de Chamita may be slightly older.

Acequia governing practices, facilitated by an elected mayordomo (boss) and three commissioners, are inherently democratic and equality-oriented: water is sacred and belongs equally to all people. Every parciante, or water right holder, pays an annual fee and is responsible for helping to maintain the ditch, including during the limpia, a big community clean out in the spring. Over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and continuing today, Santa Fe’s acequias were eroded, both literally and figuratively, often in the name of progress that increasingly positions water as a commodity.

“They’re not in great shape,” says former state historian and retired professor Hilario Romero of Santa Fe’s acequias. “Very little is left.” Romero recalls a time when the farmland around Agua Fria was the “breadbasket of Santa Fe,” fed by acequias and by the now-dry underground ojitos, or springs. In his eyes, the city’s acequias have been in trouble since 1851, when New Mexico became a territory of the United States, bringing waves of settlers and land speculation. Romero also points to the construction of dams on the Santa Fe River (four between 1881 and 1943) as eradicating the acequia system, as well the privatization of water by Thomas Catron, Confederate Civil War veteran turned career politician and capitalist, and the “Santa Fe Ring,” territorial governmental appointees bestowed with wide-ranging power. The Santa Fe Water and Improvement Company (later Santa Fe Water and Light Company, part of PNM today) built the dams, seizing most of the water for hydroelectric power.

The destruction of Santa Fe’s acequias continues today. Both Romero and Martinez have been active in fighting what they see as unsustainable and poorly planned housing developments that have destroyed historic acequias. While the majority of acequias west of St. Francis Drive no longer receive water rights, they’re still supposed to be protected by easements. In practice, however, this hasn’t been the reality.

“The water in the acequias has always been a metaphor for the Anglo-American conquest of Santa Fe,” says Kyle Maier, a historian with a focus on Canyon Road. “When Anglo-Americans started showing up with the opening of the Santa Fe Trail in 1821, they brought this concept of ‘owning’ the water. The biggest threat to the Acequia Madre seems to have been the city itself and the water utility company—in this case, PNM. Today, very few people who own property with water rights actually want to use their water.… Gentrification and the increase in property rates has had a tremendous effect on the acequia, and not in a good way.”

Every acequia, whether running or dry, deserves to be considered on its own terms. “No two ditches are alike. Every ditch is unique and different,” says José Rivera, a professor emeritus of community and regional planning at the University of New Mexico and the author of numerous books and articles about acequias including Water for the People: The Acequia Heritage of New Mexico in a Global Context, which he co-edited with Lamadrid. “Gravity flow automatically makes them different from one another because of the topography and the physics of moving water from the main head gate,” Rivera explains. “Some ditches might experience lower flows or more frequent droughts, no watering the ditch when they need it most.… People come and go and there’s resale of these properties with access to water.” He goes on to describe what’s called the “newcomer effect.”

“In general, you have two different kinds,” Rivera says. In the worst cases, a new owner won’t understand or care about their water rights. In a best-case scenario, “there are those [who]embrace and become part of it; the Stanley Crawfords who pick up a shovel and go to cleanings and the evening meetings and sometimes become mayordomos.” In Santa Fe, the three smaller acequias on Upper Canyon and Cerro Gordo are currently stewarded by mayordomos Carl Beal, Chris Ford, and B.C. Rimbeaux, who, like Crawford—renowned author and Dixon farmer—are all gringos originally from elsewhere: all three became mayordomos after their predecessors grew old and died or moved away. Even when newer mayordomos are committed and respectful, acequia knowledge is inevitably lost in the transfer of water rights away from families who’ve held them, in some cases for generations.

During the season, Rimbeaux, who has been Acequia de la Muralla’s mayordomo for the last fifteen years, arrives at the head gate at 7:30 in the morning. To make the allotment last from April to sometime in July when the monsoons (hopefully) arrive, he releases water twice a week. Even if the water no longer supports community agriculture, as acequias do elsewhere in the state (as near as La Cienega and Nambé), running water through the channels is important for supporting riparian habitat and for the overall health of the watershed. After opening the compuerta, or head gate, he walks the length of the ditch to ensure it’s flowing free of obstructions. “We don’t have the kind of flow that some of the rural acequias do; it’s small, so it doesn’t take much to stop it,” Rimbeaux says. “If you’ve got gophers, it seeps through the wall. Twigs can get caught up in the weeds, and it doesn’t take long for leaves to dam it up and [cause] overflow.” Rimbeaux says in its heyday the Muralla ran all the way to somewhere near the current site of DeVargas Center mall, hewing to the hillsides in accordance with gravity. Today, the acequia is barely a mile long and serves about fifteen parciantes. Rimbeaux says over the last several years, there’s been a great deal of turnover in properties on the Muralla and a “net loss of interest” in it.

Up the canyon from the Muralla and the Acequia Cerro Gordo, Randall Davey Audubon Center Director Carl Beal became mayordomo on the Acequia del Llano a few years ago when the longtime mayordomo moved away. “I was sort of the last able-bodied person on the ditch,” Beal says. “And I love the work…. [The acequia] is like a whole different world, this little meandering stream through a tunnel of willows.” The Llano is unique in that it begins directly at Nichols Reservoir, at a pipe that comes out the base of the dam. When the valve is open, pressure gradually forces water up a 2,500-foot section of pipe, where it spills onto the north edge of the RDAC property. (Before the dam was built, the Llano was diverted from the river.)

“When we’re irrigating, whether it’s orchards or gardens, we have to be mindful of what we’re watering and why, and how to do it as efficiently as possible,” says Beal. To that end, sections of the Llano are piped: a long stretch at the beginning that runs over an unshaded, sunbaked swath of earth, and then again near the center’s parking lot and trailhead, a high traffic area, and behind the historic sawmill-turned-Davey-House, where leaking expedited erosion. Prior to piping, the Llano seeped through the walls of the first floor of the house and down the hillside where it watered saplings planted in 1900, an eastern species of cottonwood brought to the property by Candelario Martinez, former postmaster general and probate judge who was lobbying for New Mexico’s statehood. One condition of the donation of the Davey property to the Audubon Society in the 1970s was that the gardens be maintained in perpetuity, but those stipulations were made with limited information, in a time with more abundant water. Beal is in the process of replanting a section of the lawn with native grasses, which demand much less from the acequia. The cottonwoods are at the end of their lifespan, and Beal faces a dilemma about whether and how to replace them.

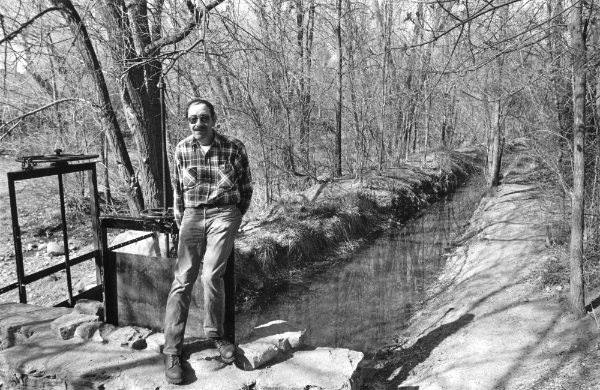

“The reason acequias continue to operate is [that]a few people will just work hard at it,” says Phil Bové, a legend in Santa Fe acequia circles for his longtime devotion to the Acequia Madre as a commissioner, and for his encyclopedic knowledge of the city’s waterways. Bové married into the Ortiz family and still lives on Acequia Madre, in the house his late wife Eleanor’s parents built. For decades, Bové says, city or state engineers have called on him to inquire about things like the locations of dry laterals, which, though no longer flowing, are still protected by easements.

“A lot of information has gotten lost over the years. I’m lucky to have grown up in the house my mother was born in,” says Phil’s daughter, Miche Bové Garcia. “But you’re not going to see that up and down the street. You’re going to see [fewer and fewer] people who have a knowledge of what that water meant for their families and generations past. Even when wonderful people move in, who are interested in preserving history, they don’t have history with it themselves. You can lose the storyline of an acequia, because you aren’t as connected to the story of the water that runs through.” Garcia is encouraging her father to write a book, compiling as much of his knowledge as possible in one place. Much of acequia wisdom is transmitted orally or in person, acquired over years in piecemeal, and written records are no longer as fastidiously kept.

The east side of Santa Fe has experienced and continues to weather waves of gentrification spanning generations. While some old-time families hang on, buying property on a living acequia in Santa Fe has been expensive for a long time. Yet each of the city’s four acequias are at some point accessible via public property: Acequia del Llano runs through the Audubon Center, where visitors can cross it on a footbridge behind the treehouse. When it’s running, the Acequia Cerro Gordo sluices down the sloping field of Armijo Park, where, at the bottom of the hill, you’ll find the Acequia de la Muralla’s head gate at the Santa Fe River. The Acequia Madre invites us to follow almost her entire length, first by sidewalk and later the Acequia Trail. Acequia Madre, everyone agrees, is the best protected of Santa Fe’s acequias and the one most likely to endure into the twenty-second century. As families are displaced from their ancestral lands (Romero says his grown sons would love to live in Santa Fe but have been priced out) the centuries-old significance of acequias is lost.

“People say I’m anti-growth. I’m not anti-growth—I just want to see things done in a sense where it’s protected and it’s compatible with what’s in the surrounding areas,” Martinez says. “It’s a part of the history that should be kept. That’s why we have archaeological reviews and archaeological reports.”

Advocating for acequias, according to those who love them, means grunt work like showing up at city council meetings. Garcia recalls her parents taking groups of students from Acequia Madre Elementary School to clean the ditch in the spring. “They’d be out there with little bitty rakes and shovels and gloves,” Garcia says. “We need to teach them the storyline of the acequia.” Romero shops at the farmers’ market, “no matter how expensive it is,” because he prioritizes the connection to his ancestral foodways.

“If there’s a lack of water flow into a ditch, it threatens the whole political, social, and cultural organization,” Rivera explains. He remembers visiting his friend, Congresswoman Teresa Leger Fernández, at her family’s ditch in Chupadero several years ago. The acequia had been dry for two years and its erosion was palpable, even though the water came back. He estimates that a ditch fades after five years without water. “It’s important to preserve them for those reasons, but it’s also personally important to feel this connection to nature and to the watershed.”

At seven miles long, including laterals, the Acequia Madre has by far the most volume, flowing from its origin at East Alameda and Los Cerros Reservoir to Agua Fria Village, where it dumps back into the Santa Fe River, when it has enough water to run its full course to the Montoyas, its final parciantes. West of St. Francis Drive, there are remnants of dozens of laterals that no longer flow or receive rights, though many rush with storm water during summer monsoons. The now-dry Acequia de Los Pinos, for instance, can be glimpsed from Baca Street (as can Acequia Madre) or at one end of Larragoite Park. Bové acknowledges that many of these acequias would probably be dry by now even if they hadn’t been cut off from the river and Acequia Madre, because of how much the water table has dropped, and the ongoing drought.

“It feels like I’m holding on to something very thin sometimes, like it’s fleeting,” says Garcia. “It’s like it’s slowly going away without people understanding how we cherish it.”

The poet Arthur Sze has lived in New Mexico for fifty years, the last ten of them with his wife as parciantes on the Acequia del Llano, on which he’s also a former commissioner. In 2021, while spending a lot of time at home and inspired by a 2009 Army Corps of Engineers environmental assessment, Sze wrote a prose poem about the acequia. “I was astonished at the number of native species, plants, and wildlife that depend on this acequia that’s only 1.5 miles long,” he says. His piece, titled “Acequia del Llano,” is printed on two laminated sheets of paper attached to a wooden box near the Acequia del Llano on Audubon property. Short stanzas alternate with more informational paragraphs, like this:

In the ditch, water flowing—

now an eagle feather wind. …

Yarrow, rabbitbrush, claret cup cactus, one-seed

juniper, Douglas fir, and scarlet penstemon are some of the plants in this environment. Endangered and threatened species include the southwestern willow flycatcher, the least tern, the violet-crowned

hummingbird, the American marten, and the white-tailed ptarmigan.

Sze notes, “Having water run along these existing acequias impacts these threatened native species.… It’s all part of a bigger ecosystem; people who aren’t on the acequia can still appreciate [its effect] on habitat along the Santa Fe River.”

“Our snowpack this winter is pretty good, but overall, the state is experiencing enormous drought conditions,” Sze adds. “When that happens, there’s a water crunch.” Sze remembers one very dry year when he was an acequia commissioner and the City of Santa Fe asked the Acequia del Llano to use less water. He recalls the complication of “owing” Texas water on certain years, due to the intricate and out-of-date policies of 1938’s Rio Grande Compact.

Romero keeps a collection of acequia maps dating back to Spanish cartographer and polymath Bernardo Miera y Pacheco’s seventeenth century rendering of the watershed and its topography. To him, acequias are as important as the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro. More recent maps are marked with blue highlighter, or dotted lines, which denote where Romero thinks an acequia once ran. He favors a “boots on the ground” approach, sometimes searching for evidence of defunct ditches under centuries’ worth of infrastructure and city planning. “I always find traces of them,” he says.

“In Santa Fe where the water is not being used to sustain families with drinking water or irrigating sustainable agriculture, we’re doing it for cultural and historical reasons,” says Rimbeaux. “We’re trying to maintain this hand-dug acequia that flows its original course.” He says even if some water is lost to seepage and evaporation, it “sustains the elm trees and riparian habitat, and if some of it goes into the ground, that’s okay. It’s not necessarily ‘lost,’ depending on your point of view.” Acequias support green space which combats the “urban heat island” effect by providing shade and keeping moisture in the ground, as well as providing migration corridors for wildlife, considerations that become even more important during the historic drought we are currently experiencing.

Santa Fe’s remaining acequias face an uphill battle, but these historic community systems offer important solutions for a water-scarce future. “They have an ability to be flexible and to change,” says Rivera. Just as no two ditches are the same, “no two seasons are alike, either.… [A]s long as irrigators hold together in this concept of solidarity, acequias can endure.”

—

Adele Oliveira is a freelance writer in Santa Fe, New Mexico.