Molten Identity

How a childhood in Santa Fe helped forge an artist’s life

By Dana Tai Soon Burgess

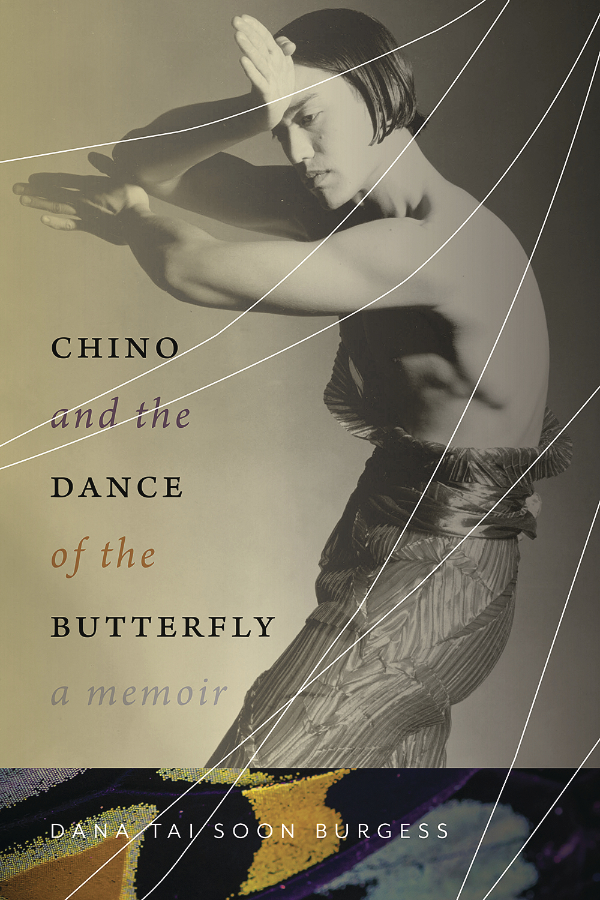

Dana Tai Soon Burgess’s new memoir, Chino and the Dance of the Butterfly (UNM Press 2022), is a deft weaving of the author’s experience with self-discovery as he realizes a life as a dancer and artist in a world that expects people of his ethnic background, Korean-American, to be a certain way and go into certain fields.

He writes in the book, as he conceptualizes a new performance: “This dance would depict the never-resolving identity and cultural struggles associated with displacement. It would, in fact, reflect my own point of view: identity struggles never really are resolved conclusively, satisfactorily. I scrawled across a page what would be the tile of this dance: Hyphen.” And then, when Hyphen was performed, he recounts: “After the twenty minutes from start to finish—as the dancers continued in movement struggles—the curtain is abruptly and purposefully closed vertically, a statement that the struggle for clarity of the hyphenated identity is never resolved. The crowd went wild wanting more and rose to their feet.”

Burgess, the choreographer in residence at the Smithsonian based at the National Portrait Gallery, spent his childhood in Santa Fe, and the early chapters of his memoir are a singular portrait of the city painted in strokes only Burgess could conjure. Here, we excerpt some of those memories of Santa Fe.

As I reflect upon the formulation of my life’s path, I always return, like a migrating butterfly, to Santa Fe. The 1970s and 1980s were a time of challenges between the forces of history and gentrification. The backdrop of Santa Fe, its residents, its adobe houses, the desert vistas, the vendors of Native jewelry in front of the Palace of the Governors, framed my cultural and sexual confusions. Chino and the Dance of the Butterfly: A Memoir is my coming-of-age story, reflections on a journey that was beautifully sculpted in the confluence of dance and visual art.

—DTSB

Three: Migration

My father seemed to me to be a towering giant. He had dark hair with highlights of gray and white, thick black square oversized eyeglass frames, hip mutton-chop sideburns that cupped his face, and a moustache that was roof to his lips. He wore a blue painter’s smock when he stood in front of his easel coaxing tubes of paint into dollops that he strategically brushed onto canvas. Abstract images emerged in crimson, cerulean, and lime, the forms always at odds with one another. Dad was experiencing what he called “a real creative block.” Carmel Valley and family life—kids cost money, after all—had siphoned from them both energy, funds, and inspiration. Their original attraction to the beauty and affordability of Carmel Valley was overturned by rising prices and an impending recession economy. Every dime earned at Origins went back into art materials.

In 1972, my parents were searching for a new community and a landscape that could re-inspire my father’s painting as well as sustain our daily needs. So, they packed up our 1961 turquoise, white-topped Volkswagen bus and drove us across the Mojave Desert in a reconnaissance mission to Santa Fe. We drove at night and slept during the day to avoid the worst of the broiling temperatures that radiated along the desert. In our cheap roadside motels, I reveled in the mechanical beds—like grown-up tin toys—that provided ten minutes of vibrating “massage” for every nickel you put in the slot. As my muscles shook on this makeshift carnival ride, I watched cloth streamers attached to the grease-blackened air-conditioner vents flap and snap convulsively in the air flow. These were quite the come down from the delicate fluttering of butterfly wings. Mom inspected all motel surfaces. She didn’t allow any of us to walk barefoot on the filthy carpets. We had to wear our seullipeo—Korean house slippers. Nor did she permit us to sleep under the motel bed sheets and covers. She lay our own sheets over the comforters and pillows, closed the blinds to block out the midday light, and pushed a dresser against the front door to ensure our security.

We drove under a star-filled sky past twenty-four-hour gas stations set into the desert sand with green AstroTurf facsimiles of suburban lawns. The air was so dry I couldn’t sweat. Instead, my skin turned red and hot to the touch and my feet and ankles swelled. I would lie back on the vinyl passenger seats, elevate my legs, and place my broad four-year-old bare feet on the van’s window glass to cool them; I stared out the window imagining the twinkling stars as celestial fingers tickling my toes. My mother said I had rice paddy feet, strong and wide, good for keeping my balance in flooded fields.

With his index finger, my brother drew an imaginary border between us down the back seat. His space was twice as large as mine. My penalty for crossing over was hard pinches and punches to my thighs. He would use his flashlight to read aloud from one of his issues of Fate magazine. These focused on thrilling paranormal phenomena, stories that set our hearts racing with fear of Sasquatches, the Loch Ness Monster, alien abductions, and battlefield hauntings. I loved the outsized drama of Ian’s reading, the entertainment of it all, in our edgy but cozy confinement. I was spellbound, too, fidgeting very little. Ian need not have feared my border trespasses. I was an audience who knew better than to do anything that might cause him to lose his place or prematurely end the show—a far more dreaded outcome than a pinch or shove.

Once we got to Santa Fe, we parked the van and took to exploring every narrow street, peering into trading posts filled with pawned jewelry and revolvers. And we poked around local art galleries, studied landscape paintings and portraits of cowboys and Indians, occasionally stopping so our parents could speak with artists in their studios. I was fascinated by the people who were blowing molten glass—how they pulled the glass from roaring fires to swiftly shape it into a vase or a dish before it cooled.

That day Dad allowed me to choose a tiny turquoise and silver ring with a stylized bear claw design, one I admired in a jewelry vendor’s display along the Santa Fe River just off the plaza. He paid five dollars to the jeweler: four crisp one dollar bills and four quarters. The expense made my eyes widen. I stared at my ring constantly, the inset stone the color of the southwestern sky. The ring was a commemoration of a moment. That day we committed ourselves; we moved from being visitors to residents. Mom and Dad had decided to rent a house on the outskirts of the city and signed a month-to-month lease.

My favorite part of Santa Fe on this trip was its cathedrals, chapels, and santuarios (sanctuaries). I had never been in a church. I was crazy about the altars. They were like a stage. Crudely hand carved and painted, they wordlessly expressed the emotions of devotion through shape and hues. At the center of each was the magnificence of Jesus, represented as a nearly naked, vulnerable man nailed to a cross.

After a week exploring our new city, we drove back to Carmel Valley, held a garage sale, bid goodbye to neighbors, packed up our essentials, and left California for good. We piled into the VW bus for a one-way trip back across the desert. Our dog Lilioukelani and our guinea pigs, Alexandra and Wilbur, traveled on the floormat in front of me, the latter in a small smelly crate. I wondered if they would die in the car. Lili panted, suffering in the heat. Wilbur didn’t make it past the second night. His desert funeral was delayed by my having to pour water on the crackled earth to soften it enough to make a small indentation into which I could ceremoniously place and then bury his little body. Would my brother and I survive this journey?

Tormento (Torment)

We moved into a small single-family adobe home on the outskirts of Santa Fe. The two-bedroom, two-bath home with a compact living room measured one thousand square feet. It was handcrafted and where the windowsills should have met the walls, there were holes where gentle breezes blew through. The landlord explained that after installing the new windows the young green wood had dried and shrunk, pulling away from the walls, but that these little holes would afford a young boy like me spy holes to see outside. Each afternoon a two-inch gap under the front door above the saddle let in a fine covering of sand to the foyer. The brick floor had been laid directly into the sand below; vacuuming was futile and would only suck more sand from the earth upward onto t he bricks. My determined mother swept each evening only to be thwarted each next day.

The house suffered from assorted uninvited creatures. Bright orange and red centipedes, each six inches long, had their nests somewhere under those bricks, near the couch. Field mice casually dallied through, and furry brown and black bats flitted near the ceilings. Rattlesnakes and grasshoppers were frequent drop-ins. We shared the space with these original occupants of the house. It could be crowded. I was more curious than afraid, for the most part.

But those moths.

They were attracted to the light that emanated from our home on the dark edge of the city. At the peak of the moths’ bombarding, between ten and eleven o’clock each night, my mom, dad, and brother performed a ritual. First, they extinguished all the lights. Then they would do their assigned tasks. My mother would grab my brother’s flashlight, bring it into the middle of the living room, turn it on, and aim the beam up at the ceiling. Meanwhile, my father would arm himself with the long suction hose of the vacuum cleaner and stand next to her; positioned at the old metal vacuum canister, my brother switched the power to ON. The wings of thousands of moths collided in frenzied flight they made for the single elongated tower of light. Their bodies thudded loudly as they were drawn into the hose and into the chamber in which they would soon suffocate. The vacuum motor whined under the strain. Once the canister was full—you could hear that it was—we would stumble in the absolute dark to our beds, calling out “goodnights” as locators. I crawled under my sheets and covered my hands, toes, and hair so that any stray moths still in the house wouldn’t take revenge on me in my sleep. The moths craved moisture and minerals. My brother said moths were dung eaters so they would especially be attracted to me. I believed him. These were not the monarch butterflies of my old Carmel Valley home. These were dull pale indelicate night monsters that clung to every part of the human body, leaving a glassy gray film of dust from their wings that couldn’t be brushed away. They were literally the monsters that go bump in the night.

I learned to navigate a land in which plagues swarmed in biblical proportions and sequence. When I turned five, the grasshoppers emerged in July and devoured every bit of green for miles. They jumped onto my clothes every time I stepped onto the open porch. I had to tear my pants off and shake them out to rid myself of them. They probed my skin with sharp feet. Grasshoppers have a dense body mass and when I pulled them, hard, off my skin, they resisted with tenacity far beyond their size. They were hideous creatures, muddy brown and puce, that angrily hummed by rubbing their angular legs together before hurling their bodies and latching on with a thump. They had the ability to jump great distances and fly with loud twitching wings. I would fight them off with sticks and stomp them under my sneakers. My brother occasionally joined my garrison. We were outnumbered and victory was hopeless. The grasshoppers were born starving in an environment that could not satiate them. As quickly as they had emerged, they disappeared back into the dry earth for another several years. The harsh desert delivered lessons.

Along with the steady flapping of moth wings and chewing clicks and predations of grasshoppers, I learned to interpret many other auditory and sensory events and movements of my fellow domestic inhabitants. The squeaking from a rusted bathroom exhaust fan meant that another field mouse had climbed the adobe walls and accidentally fell fatally into its churn. It would be trapped on a compulsory exercise wheel until Dad could come open the grate cover, holding a paper bag over the opening. Once the mouse was inside the sack, Dad released it outdoors. As cute as the field mice were, they were known to actually carry the bubonic plague, a threat that had somehow survived the Spanish Inquisition in New Mexico. True.

La Iglesia

The Santa Fe of my childhood was not yet the Hollywood branded version that it was to become. The year 1973 marked the beginning of a financial recession. It was eight years before Ralph Lauren would launch his Santa Fe Style fashion and home décor line, a decade before actor Val Kilmer would begin popping up at restaurants, and twenty years before actress and best-selling memoirist Shirley MacLaine felt the radiating crystal energy of the land and chronicled sightings of UFOs from her Santa Fe house on a hill. Santa Fe was a gritty Southwestern town that was more like a sprawling pueblo. For lack of upkeep, flat roofs sagged on adobe homes, lowrider cars prowled dirt roads that branched off main streets, and tumbleweeds blew and fastened onto barbed wire fences where they would dry to a crisp.

Santa Fe was a city with little economy and the pressures of three prominent cultures that were sometimes at odds: Indigenous, Hispanic, and Caucasian. Their relationships to the land were also varied. Although Santa Feans spoke with pride about the tres visiónes—the three visions—as a braided community, in fact the city was built on hundreds of years of conquest and conflict, land disputes, and clashes of religion.

On the main plaza, I sometimes saw children mock the glottal sounds of the Native people’s language. I hid behind my mother when we walked downtown. I thought it better to not be seen, to be disregarded as interlopers until I understood this strange new terrain.

One early impression I had of the characters in my new hometown was that “The Church” was law in this Western outpost. The Catholic churches were packed each Sunday for mass with devout señoras mayores, old ladies dressed in black, wrinkled faces behind lace veils. They devoutly clutched Bibles and rosaries. These were the old crones who cast judgment on boisterous children, girls in miniskirts, women braless in low-cut blouses, and handsome dark men that leered and posed suggestively. The señoras mayores had no reservations about reprimanding strangers, a shaming as tough love that would ensure the streets remained safe and orderly.

When I turned six, I began attending Agua Fria Elementary, a bilingual Spanish and English public school. I jumped rope with the girls in complicated rhythmic sequences. We sang out in Spanish and our feet accented the downbeat in between swings of tattered ropes. “Osito, osito, ¿puedes saltar? Ayúdame, ayúdame a contar uno, dos, tres, cuatro…” I excelled and soon was jumping between not one but two ropes. Daily the ropes were whipped around faster and faster, to push me further, until at recess an audience of older students formed a group to watch my mastery. My skills and joy were absolute. Students of all ages and teachers marveled at my timing, footwork, and endurance. Older students often assumed me to be a girl. After all, I was playing with the girls, wasn’t I? Adding to their confusion were my gender-neutral name, my pageboy haircut, and a still high-pitched voice. What did I care? I was the main event. My skills were what mattered. I didn’t care or even think about gender, mine or anyone else’s. It was irrelevant.

Soon my performances would attract a new friend. A friend other than good old Charlie. A Spanish boy, Bobby Romero, with a lisp-like accent, sky blue eyes, and black hair resembling crow feathers was never far away, smiling any time I looked up, through lunch hour and at every recess. In class Bobby moved his large, red Big Chief tablet next to mine and gently bumped his knee against me as we practiced penmanship. We loved our writing pads, the covers with the illustrated profile of a Native American tribal chief in full headdress. Bobby and I believed it was Chief Iron Eyes Cody from the Keep America Beautiful antipollution campaign on TV. As an adult I would be disillusioned by both the discovery that the proud Indigenous face on the pad was unnamed, likely a generic rendering with no real model, and that the Keep America Beautiful “Chief” was actually an Italian American actor, Espera Oscar de Corti.

Bobby and all my classmates wore Roman Catholic scapulars around their necks: blessed small square images of Christ and the Virgin Mary. Not having a scapular drew a clear religious divide between a good Catholic child and me, a heretic with no formal religion.

But I did enjoy class field trips to the Santuario de Guadalupe and the San Miguel Chapel, the oldest church in America. Those held far more fascination and excitement among us impressionable children than our trips to the sterile and abstract Los Alamos Laboratories and the lifeless State Capitol Building. We wanted magic, animation, to hear of miracles, to light votive candles, and adorn the San Miguel Chapel bell with milagros: those tiny images of body parts and supplications pressed into alloy that were reminders to God of our prayers.

These field trips have provided endless material toward my dance vocabulary. I studied the postures and gestures of each retablo, bulto, and santo, special artforms in New Mexico that feature paintings and carvings of saints. Even then, I noticed the figurines’ contrapposto— the “counterpoise”—that suggested weight borne on one leg, which caused a subtle curve of spine that ended in the slightly tilted head of St. Francis or Archangel Michael. I registered that this pose led me, as viewer, to perceive that they strained to hear my respectful salutations. The rigidity of Our Lady of Sorrows’ black robes, and red bleeding heart with a silver dagger thrust into it, conveyed her eternal deep emotional agony. Her painted glass eyes, crystalline tears, and frown hinted at softness beneath. I copied the outstretched hands of Saint Joseph and mimicked the stances of multiple Virgins, seeking to unlock what each was saying with only their body language. There were stories within each pose that I yearned to understand, to mine, and to replicate. On one field trip, while sitting in a pew holding hands with Bobby, it crossed my mind that a church was a monument to pain and suffering that in fact highlighted human sensuality and virility. Take Jesus on the crucifix. He was so handsome, with his flowing hair, defiant crown of thorns, and defined musculature. Although bloodied, Jesus’s abdominal six-pack, his lengthened sinuous biceps and deltoids, pumped pectorals, strong and well-defined thighs, and luscious long legs were absolutely beautiful. They were intended to be so. And no one ever seemed to talk about that. Why not? His was the perfect male body. I wondered why he wore a low-slung tattered garment around his hips that just barely covered his penis; was this the shameful flaw of his body, Bobby’s body, and mine as well? Jesus’s image stirred me physically on a deep level, one for which I as yet lacked words. Surely I could not be the only person to perceive and to appreciate these things in his holy male form. I sat with Bobby in the front row staring at the altar for what must have been about forty-five minutes until my teacher, Mrs. Baca, pulled us away from there and from each other. I knew no terrors of religion, nor of the shame of sexuality, to stop me from being lost in the wonder of the candle-lit images that emerged from shadows as Bobby and I intertwined our hands. Up to this time I had only seen my father’s stylized sketches of bodies and forms. This beatific experience, this potent blend of spiritual and physical arousal, was completely new and was my own. And had I known at age six what the tingling warmth was that I felt for Bobby, I would have called it puppy love. It was my first such attraction and it was to someone of my same gender.

My time at Agua Fria Elementary abruptly ended when my family had to relocate from rural Santa Fe to the Casa Solana neighborhood, just off West Alameda across from the Santa Fe River. We vacated the rental home on the outskirts of the city when the owner sold it to a family who bought it outright. On my last day at Agua Fria Elementary, I waited for my father to pick me up and take me home. Suddenly, Bobby approached. We looked at each other and he hugged me very tightly. I wordlessly reciprocated. Our embrace was abbreviated by the imminent departure of his school bus. We heard the engine turn over; Bobby whispered “goodbye” into my left ear, pulled away, bolted toward the impatient yellow bus, and clambered aboard and into the cacophony of our peers. The accordion door shut behind him, a suction seal capturing the belated passenger. I visually tracked Bobby through the windows as he made his way down its center aisle to a window seat in the back. I moved to a position in his sight lines. Once seated, Bobby searched for me, our eyes locked, we smiled wanly, and we waved at each other. As the bus began to pull away, I became acutely aware of a deep ache in my chest. I kept waving, trotting along just a few yards as well, until the bus was out of view, leaving only its tiny cloud of dirt and dust after a few stoplights beyond. For months afterward, I would think of Bobby. Always my heart ached. It does now, in fact. I have lost track of him all these decades later. Thank you, Bobby, wherever you are.

—