A Century of Antics Onstage and Off

The Santa Fe Playhouse celebrates one hundred years

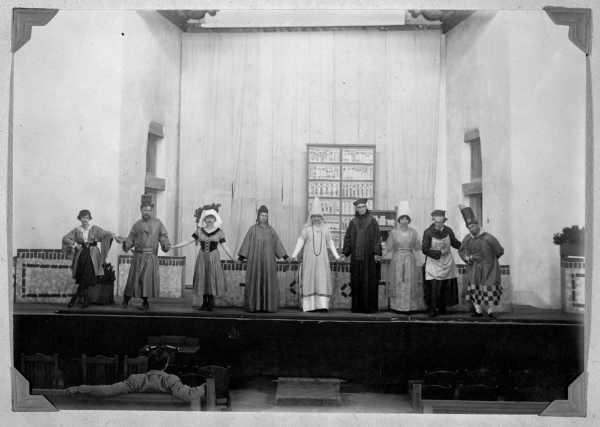

Finale of “The Man who Married a Dumb Wife,” Santa Fe Community Theater, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1919. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), neg. no. 099834

Finale of “The Man who Married a Dumb Wife,” Santa Fe Community Theater, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1919. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), neg. no. 099834

by Jennifer Levin

Art Olivas drove a friend to Santa Fe Community Theater and sat in the audience, watching the hopefuls take their turns. He wasn’t there to audition, but the director asked him to read anyway. This was in 1979, and though Olivas doesn’t remember what the play was, he ended up in it.

“I’d never been on a stage. It could’ve been the melodrama—I was in it that year,” says the former photo archivist at New Mexico History Museum. Olivas, 73, took small roles after that for about a decade, stepping into a great Santa Fe tradition begun by the author Mary Hunter Austin in 1922.

Today’s Santa Fe Playhouse was first known as the Santa Fe Players. In the hundred years since its founding, the theater has survived a slew of charismatic leaders, a world war, a pandemic, and approximately ninety-nine Fiesta Melodramas.

Amateur and professional theater groups pop up regularly in Santa Fe. With some notable exceptions, most fold in three to five years. The second-oldest group in town, Teatro Paraguas, is eighteen years old. In people years, the Playhouse could be its great-grandmother. In this cutthroat town, how and why has it endured to celebrate its centennial?

Fundamentally, it’s because the Playhouse owns its own space, while most groups must rent a stage to produce a show. But what makes its longevity all the more astonishing is that, for most of its history, the Santa Fe Playhouse was run by volunteers. In the twentieth century, it was squarely a community theater. The great contemporary debate is whether it still is.

Today, the Playhouse pays creatives for their time. The theater is run by a small staff, which includes a part-time marketing and communications manager—a role I accepted after writing about local theater for the Santa Fe New Mexican for many years. Working at the Playhouse, I found that no official written history exists. So, I’ve attempted to piece one together. But what follows is just a start, because this story could fill a book.

Anticorporate origins

The first production of the Santa Fe Players was Anatole France’s The Man Who Married a Dumb Wife on Valentine’s Day in 1919, presented in the St. Francis Auditorium at what was then called the Museum of Fine Arts. It was directed by Mary Hunter Austin, a social activist and author of Indigenous themes who’d relocated to Santa Fe from California the year before. Austin belonged to a group of white transplants who had a lasting influence on Santa Fe culture, including artist Will Shuster, poet Witter Bynner, and architect John Gaw Meem.

“Mary Austin’s objective was to do international, national, and local plays that mattered, that would get the community involved and start a conversation,” says Kent Kirkpatrick, president of Santa Fe Playhouse’s Board of Trustees.

Austin was inspired by the Little Theater Movement, a national effort to combat corporate control of most U.S. venues, which booked traveling shows with mass-market appeal. The Little Theater Movement called for greater artistic exploration and was promoted by the likes of Nobel-winning playwright Eugene O’Neill, a founding member of the Provincetown Players. Austin and her group incorporated in 1922, the same year they produced Santa Fe’s first Fiesta Melodrama, The Sorcerers of Nambe. It was directed by J.D. DeHuff, then superintendent of Santa Fe Indian School, with sets by renowned painter Gerald Cassidy.

The Santa Fe Indian Market began during the same Fiesta, held against the backdrop of the DeVargas Pageant (also known as the Entrada) that re-enacted the “peaceful reconquest” of Santa Fe in 1693, after Spanish colonists were driven out by the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. Fiesta emphasized what were considered Santa Fe’s three distinct cultures—Native American, Hispanic, and Anglo-American—supposedly living in harmony. Fiesta was one of many tourism initiatives designed as a pathway to statehood for New Mexico, as was the tri-cultural identity—but it wasn’t all that accurate.

“Despite the rhetoric of social tolerance, and despite the unifying image provided by the ubiquitous adobe-colored stucco, the myth of Santa Fe obscures long-standing cultural and class frictions,” Chris Wilson writes in The Myth of Santa Fe, published in 1997.

Former Playhouse Board President Kelly Huertas says the Santa Fe Players probably held the first melodrama “because they thought they could sell tickets. I don’t think they intended to insert themselves into the tri-culture controversy.”

But that’s exactly what they did. Since 1922, a Santa Fe Fiesta Melodrama has been performed almost every year. The jokes usually twist on cultural differences, and it’s all supposed to be in good fun. Despite their embrace of local customs and people, the white Santa Fe Players displayed the same clueless racism that was common in America at the time. An undated photo housed in the New Mexico History Museum Photo Archives shows Will Shuster, Witter Bynner, and their friends performing a minstrel show in blackface.

Barebones theater

Plays in the first half of the twentieth century included A Night Wind, directed by Witter Bynner, in 1931; The Ninth Guest, written by Owen Davis and directed by Mel Marshal in 1939 at Harrington Junior High School (which closed in 1976 and was replaced with Capshaw Middle School); and Eugene O’Neill’s Anna Christie, directed by Dave Hyatt and performed at a mysterious location called only “Loretto Hall” in January 1941. The Legend of Dallas Lee, written and directed by Judy Warner, ran for three days in May 1955 at St. Michael’s College Playhouse—a barn that predated the Greer Garson Theater at what would later be called the College of Santa Fe. New generations of Players kept the group going, at some point changing the name to Santa Fe Little Theater and then to Santa Fe Community Theater.

We know the group went dark for a few years during World War II. They performed in school auditoriums and on makeshift stages in empty lots, often staging the Fiesta Melodrama at the Rodeo Grounds. Once, sometime in the 1950s, they held it in an empty hotel swimming pool, with the audience gazing down upon the actors. In 1961, they wrote the Fiesta Melodrama in-house for the first time, instead of adding Santa Fe references to an existing script. It’s been written in-house ever since, the writers kept anonymous to protect them from public backlash.

The itinerant theater group also staged small productions at Three Cities of Spain Restaurant on Canyon Road (where Geronimo is today). “I lived next to the restaurant, and the two men who ran that were talking about getting a building,” says Bob Sinn, who acted in productions from the 1960s onward. He joined the board in 1991 after retiring from a career in social work. He served as part-time managing director for several years, an all-consuming job for which he was paid $350 a month.

The restaurant owners, Bob Garrison and David Munn, might have been among the original buyers of the Santa Fe Playhouse, but the names on that long-ago deed are lost to history. A picture taken when the theater opened in 1962 shows Anabel Haas, Robert Jerkins and Joe Paull (who were a couple), Dorothy Best Donnelly, and Thomas A. Donnelly outside the front doors of the nineteenth-century adobe on DeVargas Street.

The structure was built in the 1890s as a livery stable and later became an auto repair shop. It barely resembled a theater, but it was theirs. They sectioned off an area for the stage and carted in folding chairs. As time went on, they built a makeshift dressing room that rested against the back of the building, and erected a real stage—although a structurally important pole stood in the middle of it until at least the 1970s. A second pole, in the audience area, was removed in the late 1980s or early ’90s—no one remembers exactly when.

Jim McGiffin, a New York native who performed at the Playhouse for the first time as the villain in the 1979 Fiesta Melodrama, says the pole was definitely still on stage when he got there. “I remember swinging around it, pointing at people, and doing nasty, villain things.”

The heyday

Jean Moss moved to Santa Fe in 1972 from New York, where she’d intended to become an actress.

“But I didn’t do it. I was terrified of the extraordinary commitment that I had when I was working,” says the 81-year-old rare books dealer. “Theater is the closest thing I have to religion.”

In New Mexico, she auditioned for Santa Fe Community Theater’s production of Summer and Smoke, by Tennessee Williams. “I didn’t comb my hair or put on lipstick. I just ran down to the theater. I remember it was very quiet when I auditioned because no one had ever seen me before.”

She didn’t get the part, but director Cather MacCallum cast her as Sonya in Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya in 1974. Moss went back to New York for a few years soon after, but returned in 1980 and joined the community theater’s board. Moss recalls there being a few paid staffers in the 1980s, including an office administrator and a technical director, but everyone else worked for free.

In 1982, Moss directed Cake, which Witter Bynner wrote for the Players and published in 1926. Produced in honor of the theater’s sixtieth anniversary, the theater paid no royalties and received financial support from the Santa Fe-based Witter Bynner Foundation. Moss recalls that they paid no royalties when they did Chekhov plays, either, because they adapted their own scripts. She says the seasons were made up of classics, contemporary works, and musicals, as well as the epitome of community theater, the Fiesta Melodrama.

“That’s where a lot of people without theater experience got their start, and then they would become more involved. But the melodrama was always separate from everything else that was going on. It was its own thing.”

The 1970s and ’80s were the heyday of the community theater movement, which was an evolution of the Little Theater Movement that relied on volunteer support. Like others of its ilk, Santa Fe’s was supported by dues-paying members. But membership dwindled over the decades, and soon the $25 annual dues didn’t stretch as far as they once had. Most of the people from this era have died, but one important name is Marion “Jinx” Junkin, who founded Jinx’s Magic Theater in 1968 and The Theater of Music in 1980, both in Santa Fe. Another is Marty Stone, who took a leadership role starting in the mid-1970s, and was known as “Mr. Theater.”

“He was a force of nature,” Olivas says of Stone. “He was the living embodiment of Zero Mostel as Bialystock in The Producers. He could talk you into anything.”

Stone convinced residents of the nearby retirement community to buy season subscriptions. He talked strangers on the street into auditioning for plays. He rescued seating from a synagogue dumpster and finally replaced the folding chairs in the audience. But his bookkeeping was sloppy—donation information was scribbled on scrap paper and unidentified receipts piled up in the box office. When he moved to California in the late ’80s, board upheaval followed and some of the core actors drifted away. Moss left the board at this time, though she continued to be involved for a few years, directing Uncle Vanya in the 1988-89 season.

McGiffin, the aforementioned pole-swinging villain, and his wife Carol met during the 1979 Fiesta Melodrama. They co-directed shows throughout the 1980s until starting their family, and remained involved from time to time. McGiffin, 73, last acted at the Playhouse in 2017 in The Normal Heart by Larry Kramer, directed by Duchess Dale. He also appeared in a video projection featured in that season’s adaptation of George Orwell’s 1984. McGiffin is a community theater devotee who says the Playhouse should remain what it always was. “The only thing they do now that’s like community theater is the melodrama. It’s too corporate now,” he says. And it doesn’t offer shows he wants to see. He prefers family-friendly musicals to “some play where two people ponder the possibilities.”

Asked what he’s referring to, he says, “I don’t want to see Waiting for Godot” (despite the Playhouse not having produced Beckett’s classic in any recent memory).

Moss disagrees. “I would love to see a great production of Waiting for Godot!”

The push for professionalism

Argos MacCallum arrived at the theater soon after Stone left. The Santa Fe Preparatory School graduate had been involved with other local theaters, including the Theatre of All Possibilities, before coming home to where he’d spent parts of his childhood watching his mother, Cather, run rehearsals. He began acting in and directing shows, and using his carpentry skills to improve the building. He joined the board.

“They were involved in a huge renovation. They got rid of the pole in the audience, and the stage got raised,” says MacCallum, 70. “I did a lot of work on the remodel. I don’t remember who was president, but Rebecca Morgan was very instrumental at the time.” Morgan ran Southwest Children’s Theater and served on the Playhouse board for many years, and managed the Playhouse in the 2000s. She died in 2021, at age 69.

Catherine Owen moved to Santa Fe in 1993 to work for New Mexico Repertory Theater, but the Equity house (a theater employing talent from the Actors’ Equity Association) operating in the Armory for the Arts closed six months after she arrived. The board hired her in 1995 as the full-time managing director. They changed the name to Santa Fe Playhouse in 1997, in an effort to distance themselves from the stigma for uneven quality that had come to be associated with “community theater.”

Argos MacCallum was ambivalent about the name change, but says that as soon as they became the Santa Fe Playhouse, “ticket sales shot up.” He wanted to produce Spanish-language and bilingual theater, so he eventually left to found Teatro Paraguas. He remains a driving force in the Santa Fe theater scene, sitting on several boards and serving as ad-hoc advisor to anyone who seeks his counsel.

Sinn, 83, says he was invited to leave around the same time. “The theater fell on me after I retired. I thought I knew what my life was going to be, and then I got sucked into this. … Most of my memories are when we had community theater. The one thing we had was fun. That’s what held us together. And the mortgage. If you have to pay the mortgage every month, you might as well put on a play.”

During this era, directors included T. Kent Crider, Lucinda Marker, Janice Bonser, Richard Block, and Clara Soister. In the 1994-95 season, Crider directed an ambitious production of The Kentucky Cycle, by Robert Shenkkam, a Pulitzer Prize-winning series of nine one-act plays that required audiences to come back over two days.

“We found out later that the playwright was actually here in town when we were doing it, but he didn’t come see the play. You never know if they’re here or not,” said Sinn.

Owen, 63, admits that she and Sinn clashed. “He had a different focus of what he wanted to do, and he left. It was hard. I felt bad about it. But I had things that had to get done.”

She says changing the name was not about abandoning the theater’s origins, but about looking to the future. “Community theater is the hardest theater you can do. You work on little to no money, mostly volunteers. It was hard for community theaters to keep going, but those that did survive became playhouses, like the Pasadena Playhouse. I felt it would be a natural transition. It would help me grow the theater, and I knew the artistic quality could be better because we have the talent here.”

The Santa Fe Playhouse did away with its membership fee and became a 501c3. Owen wrote grants, increased rental income, and got new seating, among other upgrades. After a fire decimated the dressing room in 2000, she renovated the back of the building. She also started annual LGBTQ productions and the one-act playwriting competition Benchwarmers, which featured ten ten-minute plays where the only set piece was a park bench—and which ran until 2019 (and then become a casualty of the pandemic).

“I was able to start getting individuals to donate larger amounts of money,” says Owen, who left the managing director position in 2005. “I had many conversations with Robert Jerkins and Joe Paull, and when Robert passed, he left his estate to the theater.”

The modern era

Georgia native Kelly Huertas landed in Santa Fe in 1992 by way of New York City, where she’d grown tired of the drama in the independent theater community. She bartended at Cowgirl and once stumbled into the Fiesta Melodrama, which she didn’t entirely understand because she was new in town. In 2009, she wrote a play that was accepted into the Benchwarmers competition. She had another play accepted in 2010, and in 2011, she joined the board.

“I’d moved here to get away from theater politics,” she says, “but, I thought, this was small and I could handle it.”

The board was full of actors and directors. They were happy to work concessions, paint sets, and clean bathrooms, but the finances were a mess. They’d paid off the mortgage with Jerkins’ estate gift, and the remainder—around $1 million, depending on how the market was doing—was used to make up for annual budget shortfalls.

“Someone said, ‘When the money goes away, we’ll just let the next board deal with it.’ That really got under my skin,” Huertas says. It was time to stop relying on volunteers to run everything, or someone taking charge out of a sense of obligation, as Bob Sinn did when he came out of retirement and worked for a pittance.

Huertas, 59, became board president in 2013 and instituted a new infrastructure, hiring an artistic director, technical director, and office administrator. But the first staff quit en masse in less than a year, citing burnout. “None of us had any idea what it took to run a theater,” she admits. “We wrote job descriptions, but we were asking them to do more than was humanly possible.”

They brought in Vaughn Irving as the new artistic director. Irving grew up in Santa Fe, seeing Fiesta Melodramas as a teenager before going away to college and then acting in regional theater, teaching, and writing plays. “The board framed the mission as, ‘We want to be more professional; we don’t want to be a community theater anymore,’” he says.

Irving, 38, produced comedies, musicals, new works, and locally written plays, trying to see what would bring in audiences. But it wasn’t as though he suddenly closed auditions to the public and started only hiring Equity actors. Irving cast widely from the community, including students from Santa Fe University of Art and Design, which infused the Playhouse with youthful energy.

He says the most basic way to distinguish between community and professional theater is that the former relies on volunteers and the latter pays. “But I don’t think it gets at the heart of the question, which is: Who is the primary audience you’re serving?” Irving posits. “Community theater is about providing creative opportunities for the people in the community. Hopefully, the audience enjoys the finished product.”

Compare this to professional theater, where “we’re serving a mission to offer something to the community, not to provide an outlet for the community to do theater. Theater is our tool to create community, shared experiences, and dialogue,” says Colin Hovde, 41, the Playhouse’s current executive director.

In late 2019, Irving left the Playhouse to move to Chicago to pursue a graduate degree in arts administration (though he has since moved back to Santa Fe to serve as president of LiveArts Santa Fe, a nonprofit seeking to establish community and academic programs at the Greer Garson Theatre Center). He hand-picked his replacement, Robyn Rikoon, who lived in Santa Fe until she was 14. She’d been coming back in recent years to act and direct, including directing the 2017 production of 1984. Hovde joined the staff in 2021, when the Playhouse was closed to the public due to the coronavirus pandemic, which turned the theater world inside out.

Once More Unto the Breach

Rikoon left Santa Fe for boarding school in 2000, after her older brother died. She moved back almost twenty years later, just days after her partner unexpectedly passed away.

“I was in a state of shock,” says Rikoon, 36. “I don’t think I consciously made the choice to take the job. It’s like the choice was made for me.”

She’d been acting in regional theater for several years, and got her first chance to direct at the Santa Fe Playhouse, starting with short Benchwarmers scripts before moving on to the aforementioned 2017 production of 1984. After that, she accepted a directing fellowship at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., where she reconnected with Hovde, whom she knew from North Carolina School for the Arts, where they both went to college. He’s the first person in a generation to bring substantial theater management experience to the Playhouse, which he calls “a hundred-year-old startup.”

Becoming an artistic director was a dream come true for Rikoon. Then, almost immediately, the pandemic hit, and she was forced to cancel her first season. She put some theater pieces online, including the 2020 Fiesta Melodrama, which she co-directed with Andrew Primm as a series of socially distanced shorts, filmed outdoors.

Reviving live theater in the waning days of the pandemic has been challenging. Shows have been delayed due to illness in the cast, and there is a general sense that many of the people who supported the Playhouse in the past haven’t come back. It’s unclear whether that’s due to rising ticket prices, fear of crowds, or other issues. Rikoon and Hovde would love to rebuild the volunteer core, upon which many theaters rely for concession work, ushering, and other duties.

“I don’t intend to take the theater away from the community, so I get super riled up when people have these ideas about it,” she says. “Just because we’re trying to create ‘better’ theater, whatever that means, that doesn’t mean it’s not for the community. I hold an open audition once a year, in December, for everyone who wants to act at the Playhouse, and then I do callbacks for the individual plays.”

The board is now made up of professionals—rather than artists—with legal and marketing experience, fundraising and networking chops, and other skills that can help steer a theater while leaving the artistic decisions to the artistic director.

“Our mission is to do new plays, and Robyn’s taste is extraordinary,” says Board President Kirkpatrick. He hopes that someday soon the Playhouse will be regarded as a small regional theater, rather than a community theater, but that there’s nothing wrong with existing somewhere in between. “I want the Playhouse to always be important to the community. We want people to come because we offer something they enjoy and that makes them think.”

Coda

The hundredth-anniversary Fiesta Melodrama, presented in August and September of 2022, was titled A Proud Playhouse Presents a Preeminent Pageant to Puncture the Precious Pretensions of a Pretty Provincial Populace, or A Silly Centennial Celebration Centered on the Scintillating Scandals of Santa Fe, or A Riotous Retrospective Chock Full of Gags. It was supposed to be a greatest-hits show, reflecting on a century of skewering anybody and everybody in the City Different. But when the cast, crew, and other volunteers began reading through old scripts, they realized that the Fiesta Melodrama has always been, in a word, problematic.

Times have changed and so has Fiesta. Indian Market long ago became independent of white oversight and is held earlier in August, and the Entrada was canceled in 2018 after mass public outrage at its selectively edited version of history. “You could say or do things a hundred years ago, or forty years ago, that no one blinked at, but these jokes come across very differently now and are taken in a completely different way,” says Andrew Primm, who co-directed this year with Eliot Fisher.

The result was a play that put the melodrama itself on trial, in an attempt to look back and reckon with its history while authentically engaging Santa Fe’s tri-culture in the context of larger social change.

“In the play itself, we’re talking about how traditions change, but that traditions are people,” Fisher says. “The Melodrama is what we want to make it, any of us. That’s the same as our city.”

Fisher, 39, directed his first Fiesta Melodrama in 2006. Primm, 50, joined him in 2011, first as the play’s hero and then as co-director. They’ve shuffled duties most years since, bringing in others when needed. Both were born and raised in Santa Fe, though Fisher moved to Austin, Texas, a few years ago to pursue his doctorate in performance as public practice. Primm is a well-known local musician, producer, and cinematographer whose melodrama bona fides date to 1959, when his uncle was in the show and his aunt sewed costumes.

Fisher’s interest stems from his time playing piano for the Madrid Melodrama at the Engine House Theater. When he found out Santa Fe had a melodrama of its own, he walked into the Playhouse and asked how he could get involved. He was immediately welcomed by Rebecca Morgan, who saw potential in the recent college grad with a passion for old-timey hijinks.

“I don’t want to be grandiose,” he says, “but the reason I’ve been involved for so many years, and the reason I love it, is that the melodrama allows us to let our guard down enough to see ourselves and each other anew, and maybe even inspire us to take some action in our lives. We raise our voices in approval or discouragement at various things in our town, about how we live. It’s very much like the democratic process itself. That’s getting very serious about something that is super silly, but it’s genuine for me.”

—

Jennifer Levin is a freelance writer and communications professional in Santa Fe, New Mexico. As a journalist, she writes primarily about arts and culture. She grew up in Chicago and holds a bachelor’s in creative writing from the College of Santa Fe.