Supernatural

Get spooked by the history and pop culture of Japanese yōkai

Terai Ichiyu, white hannya noh mask, 2017. Wood (cypress), natural paints (shell, mercury, carbon [sumi], ocher, gold), cotton cord. 10 5⁄8 × 6 11⁄16 × 4 1⁄8 in. International Folk Art Foundation, Museum of International Folk Art (FA.2018.33.1). Photograph by Addison Doty. A hannya is a female demon. This mask

represents a woman transformed into a demon by jealousy and rage. During a noh performance, the mask must portray various emotions, such as ferocious rage, fear, and extreme sadness.

Terai Ichiyu, white hannya noh mask, 2017. Wood (cypress), natural paints (shell, mercury, carbon [sumi], ocher, gold), cotton cord. 10 5⁄8 × 6 11⁄16 × 4 1⁄8 in. International Folk Art Foundation, Museum of International Folk Art (FA.2018.33.1). Photograph by Addison Doty. A hannya is a female demon. This mask

represents a woman transformed into a demon by jealousy and rage. During a noh performance, the mask must portray various emotions, such as ferocious rage, fear, and extreme sadness.

BY JULIA GOLDBERG

The demon’s white face first appears subsumed with rage, a fearsome figure with foreboding gold horns and fangs protruding from a pained grimace. Its eyes also shine gold—a color signifying the supernatural. But look more closely and you will see another face in the mask: that of a woman consumed and transformed by emotion.

This white hannya noh mask by Japanese artist Terai Ichiyu is one of approximately 125 items in the Museum of International Folk Art exhibition Yōkai: Ghosts and Demons of Japan, which opens December 6, 2019, and will remain on view through January 10, 2021. The exhibition features other contemporary objects depicting yōkai, such as costumes, toys, and comic books, while accompanying scrolls and woodblock prints that connect to historic periods in Japan’s history illuminates yōkai’s extensive lineage. The museum has also worked with a yōkai-centric art collective in Japan to create an immersive and interactive obake yashiki, a Japanese ghost house situated within the exhibition. Films, a symposium, performances, and other events also are in the works.

The museum commissioned this particular hannya mask in 2017. Noh is a classical form of Japanese drama dating to the fourteenth century, and hannya masks are commonly used in such performances, which frequently depict characters from traditional Japanese literature. This mask references the character Lady Rokujō from the eleventh-century work The Tale of Genji, which was adapted for the noh play Aoi no Ue. Once a noblewoman, Lady Rokujō believes Hikaru Genji loves her and is going to leave his wife for her, only to discover that his wife is pregnant. Consumed by jealousy, rage, and humiliation, she transforms into a demon.

“What’s spectacular about this mask is the emotion you see on her face,” says Felicia Katz-Harris, MOIFA’s senior curator and curator of Asian folk art, noting the mask not only depicts a demon that is frightening in its own right, but also frightened and confused by what she has become.

“When you tilt her in certain ways, you see that sadness or the fear in her face,” she says. “It’s a scary thing when you lose control of your emotions.”

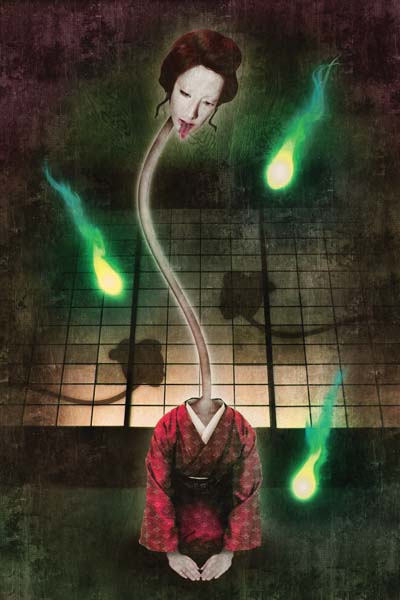

The exhibition takes an expansive view of the term yōkai—allowing the name to encompass demons such as the one depicted in the hannya mask, along with ghosts, shapeshifters, monsters, and myriad other embodied supernatural beings. Yōkai have played an important role in Japan’s popular culture for at least 400 years, but folklore links yōkai to ancient times. The stories behind the images hold particular importance in MOIFA’s exhibition, the first United States museum show devoted to yōkai.

While Katz-Harris admits to a certain preference for the yōkai stories involving “vengeful female ghosts”—of which there are many—the show will capture the wide array of creatures and stories.

The exhibition grew around one item in particular: a Namahage costume the museum commissioned in 2012 at the suggestion of Michael Dylan Foster, yōkai scholar and chair of East Asian languages and cultures at University of California at Davis. He has written extensively on yōkai, and conducted fieldwork on the Namahage ritual and festival, an annual event in Japan’s Akita prefecture.

During the ritual, men in demonic masks travel from house to house, Katz-Harris explains, “calling out children by name, finding out who’s been naughty, threatening them that they’re going to be taken away, and then leave when they promise through tears and sobs that they will be good in the coming year.” The costume is “what first put the idea in my head,” she says. “Because we had this costume, but we didn’t really have plans for it.”

Then, in 2013, Katz-Harris curated the MOIFA exhibition Tako Kichi: Kite Crazy in Japan. “What really struck me during the development of that show was the folklore related to Japanese kites, because a lot of kites depict images of warriors or different folklore heroes,” she says. “Learning about these different depictions really drew me into the folklore, and that blew me away.”

That exhibition also marked the first time Katz-Harris studied Japanese woodblocks in depth. “I’m enamored by the art of woodblock printing in Japan,” she says, in part because of their precision and craftsmanship, but primarily because of the “narrative aspect.” Such folklore appealed to Katz-Harris, who has a master’s degree in cultural anthropology. “The stories and the meaning behind the prints are what really interest me,” she says.

Following that show, in 2016, Katz-Harris curated Sacred Realm: Blessings & Good Fortune Across Asia. Attendees were given the opportunity to contribute suggestions for future exhibitions focused on Asian arts and were provided several options from which they could choose; Japanese ghosts and demons was one of them. “It seemed to be the most popular,” Katz-Harris says and, in response to the interest, she dove into the topic. “It’s been such a fun way to explore Japanese art and culture,” she says, “through the lens of these monsters.”

Vengeful spirits. Angry inanimate objects. Sea creatures. Shapeshifting foxes.

Yōkai characters have been a presence in Japanese culture for centuries, with their images appearing on scrolls as far back as Japan’s Muromachi period (1336–1573). These include the famous Hyakki Yagyō scroll (Night Parade of 100 Demons), the earliest known version of which dates to the early sixteenth century. According to folklore, the demon parade took place on a famous street, Ichijo-dori, which ran east and west through the ancient capital, and was considered a thoroughfare between the everyday and otherworldly realms.

“It was said that this was a horde of monsters and demons that rolled down this street at certain times at certain dates, and you were to avoid that at all costs,” Katz-Harris says, because “even looking at them … you would meet your demise.”

The original scroll painting, she notes, has been subject to different interpretations. Some believe it depicts the demon parade. Others believe the painting captures the confusion about societal changes following the end of the Ōnin War (1467–1477), which shifted a heavily regulated feudalistic culture to one in which the country was less isolated, when ideas and information began to filter both in and out of its borders.

Today, the street lies in the Taishogun shopping district in Kyoto. It was re-envisioned more than a decade ago to pay homage to its yōkai heritage, with yōkai statues, the Mononoke Ichi (ghost flea market), and various reimagined shops, such as a yōkai ramen shop. The street also hosts an annual re-enactment of the parade, for which people make costumes that have to be somewhat based on the monsters from the scroll, Katz-Harris says.

A group of yōkai artists helped officials redevelop the street, and also are involved with the MOIFA yōkai exhibition. Katz-Harris learned of the group during a research trip to Japan. A friend and interpreter, whom Katz-Harris had met while curating the kite exhibition, had taken her to the Japan Oni Exchange Museum, a demon museum located at the bottom of Mount Oe. The area is renowned for its yōkai legends, particularly those related to Shutendōji, “a horrible demon who was eating children, killing people, kidnapping women, that sort of thing.”

The museum’s director suggested she contact Junya Kōno, a lecturer at Kyoto Saga University of Arts, who leads the art collective Hyakuyobako (Box of 100 Yōkai). In addition to its work in the Taishogun district, the collective also creates haunted yōkai houses and train rides.

When Katz-Harris met Kōno, the two immediately began brainstorming. “I just knew right away he was going to be an important collaborator and friend of the exhibition,” she says.

Kōno visited Santa Fe last November and this September, and helped create the exhibition’s haunted house. With his students, Kōno also produced the exhibition’s Japanese-style ghost story-telling video for attendees to view on their way into the house.

Some of the yōkai stories are unquestionably gruesome, but perhaps what makes them particularly significant is how pervasive they are in not just Japanese popular culture, but globally. As such, the field of yōkai encompasses not just myriad creatures, but scholarly debates, philosophical ideas, and history itself.

As nomenclature, yōkai withstand constriction.

In a book that will accompany the exhibition, scholars, artists, and other experts examine the yōkai phenomenon through a variety of lenses. In her introductory chapter, Katz-Harris notes that while yōkai’s “status is commonly described as ‘supernatural,’ yōkai intermingle with and appear in the natural, human world. They straddle borders, defy dichotomies, escape time, and resist strict classification.” As such, “They are uniquely understood at different historical moments and by different people, genres, and disciplinary perspectives.”

The phenomenon of yōkai has changed and shifted over time, with increased popularity during certain eras. Foster identifies these time frames as “yōkai booms,” Katz-Harris says, “peaks in history where yōkai seem to have been really popular with the masses.”

The first boom occurred during Japan’s Edo period (1603–1867), in which yōkai imagery appeared in a variety of forms, including on decorative toggle beads known as netsuke, decorative sword elements, illustrated woodblock prints called ukiyo-e, as well as illustrated, woodblock-printed books, or kusazōshi. A leading artist of the time, Toriyama Sekien, created what was essentially an eighteenth-century yōkai encyclopedia, drawing creatures depicted in the Night Parade of 100 Demons, which codified yōkai imagery and led to its proliferation in the popular culture of the time and thereafter.

Renowned yōkai scholar Komatsu Kazuhiko, Katz-Harris notes, has said that interest in yōkai historically has waned during events such as World War II when, presumably, “there were much more important things to think about.” After the war, however, another yōkai boom commenced. It was during that boom that Japanese manga (comic) artist Shigeru Mizuki created his series GeGeGe no Kitarō, which tells the story of a monster boy and his monster family, and which remains popular to this day. The stories Mizuki wrote were based on older ones he heard from his nanny.

“So that brought yōkai into contemporary popular culture as manga,” Katz-Harris says, “and then it was anime because they made cartoons about it.” From there, other yōkai artists developed more manga and other artwork, but Mizuki was key in that development. And today, “a lot of people who are enthusiasts of yōkai think of yōkai stories they know or characters they know and they attribute them to Mizuki, yet [his] characters are very much based on these old folklore ideas.”

A contemporary depiction of GeGeGe no Kitarō’s titular Kitarō that Katz-Harris acquired in Japan is also featured in the show.

Yōkai’s pervasive presence pops up in surprising ways across the globe. Pokémon, “pocket monsters,” have clear yōkai influence. “I didn’t know that until I began this project,” Katz-Harris says. For example, a Pokémon character named Ninetales has clear connection to a powerful fox yōkai: Kitsune. The Pokémon character Shiftry shares many attributes with the yōkai known as a tengu, a red-faced dog-like creature with a distinctive long nose that is sometimes depicted with birdlike features.

Yōkai stories and characters also show up in contemporary film. The blockbuster horror film The Ring, based on the Japanese film Ringu, connects to an ancient Japanese ghost story about a servant girl named Okiku. A cruel samurai killed Okiku by throwing her down a well, only to be haunted by her ghost afterwards.

“It was a popular ghost story, and then it became a popular subject for kabuki theater, and then a popular subject to all sorts of artwork,” Katz-Harris says.

In curating the show, yōkai’s connection to popular culture emerged as its focus.

Many of the objects come from the museum’s permanent collection, which includes 16,000 pieces from Japan. In collecting new items, Katz-Harris purchased contemporary crafts and artworks that built on the extant collection to “let us get into the stories of these yōkai.”

She hopes to invite a priest from the ancient Dōjō-ji Temple in Wakayama so that Santa Fe visitors can experience the stories as living tales. The temple is connected to a ghost story performed over the years in a variety of forms, including noh and bunraku puppet theatre. At the temple, the priest uses the scroll painting to help recite the story the images depict.

In the story, a spurned maiden named Kiyohime becomes a demon and avenges herself by burning alive the man who deceived her while he hides, with the help of the temple’s priests, in the temple’s bell. Katz-Harris hopes to recreate the performance of the story in Santa Fe as part of the exhibition, also using the scroll that depicts the tale. She also has commissioned a bunraku puppet of Kiyohime, who transforms from girl to demon through the use of the puppet’s levers.

Katz-Harris also intends to hold a symposium during the exhibition in which the many collaborators and contributors can share their expertise with and enthusiasm for yōkai with the public.

“This has been so much fun to research and explore, and all the artists and scholars have been so generous with information,” she says. “They’re passionate about the topic.”

That passion has been contagious, she says.

“There are these ghost stories that really speak to me,” she says. But besides the traditional yōkai stories and culture, “I have found contemporary urban legends to be just as compelling,” she admits. “And it’s ironic, but I’m not a ghost story person. As a kid, I hid in the bathroom when girls told ghost stories at sleepover parties because I couldn’t handle it, and haunted houses were definitely not my thing.”

These days, Katz-Harris recites blood-chilling tales without blinking an eye—and while plans for the participatory elements of the exhibition are still under development, she says, “We’re hoping there will be a few jump scares.”

Julia Goldberg is a journalist and teacher in Santa Fe, New Mexico, as well as the author of Inside Story: Everyone’s Guide to Reporting and Writing Creative Nonfiction.