Family Ties

Gifts from friends–members of New Mexico’s original art colony–find their way home.

Gene Kloss, Penitente Fires, 1939. Drypoint and etching. 11 × 14 in. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of Leonora Culbert Welsher in memory of her grandfather, John Pickard, and her mother, Caroline Pickard Culbert, 2018.

Gene Kloss, Penitente Fires, 1939. Drypoint and etching. 11 × 14 in. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of Leonora Culbert Welsher in memory of her grandfather, John Pickard, and her mother, Caroline Pickard Culbert, 2018.

BY KATE NELSON

Back in 1917, John Pickard had a problem. A renowned art historian and archaeologist at the University of Missouri, he was leading the charge to commission murals, statues, tapestries, stained-glass windows, and bas-reliefs for the new state capitol in Jefferson City. In search of inspiration, he visited other states’ capitols, but they left him cold. Too Grecian, he thought, and disconnected from each state’s unique personality.

Missouri considered itself the Gateway to the West—a place of risk-taking industrialists, burly miners, and hardy farmers, but also of Native Americans, grand landscapes, and the smoldering embers of Manifest Destiny. Pickard knew a lot of artists, famous ones, people he could tap for various parts of the capitol design. But even the ones who could claim Midwestern roots had embraced East Coast and European aesthetics. To properly evoke Missouri’s westward-leaning bona fides, he needed artists who knew the West. The closest he could come was a fellow in St. Louis who was a founding member of the two-year-old Taos Society of Artists.

Oscar E. Berninghaus helped blaze Pickard’s trail to New Mexico, where a covey of artists soon busied themselves with Missouri-bound work. Equally enchanted, the Pickard family established a Taos homestead of their own. And nearly a century later, one man’s desire to accurately represent the West in Missouri has turned into a New Mexico Museum of Art donation filled with the small-town storied charm of New Mexico’s original Anglo art colony.

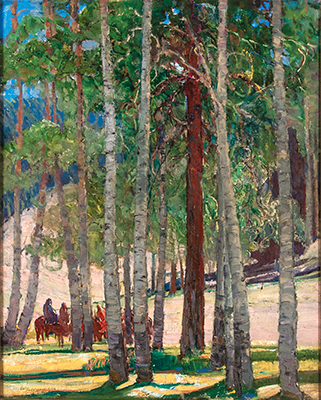

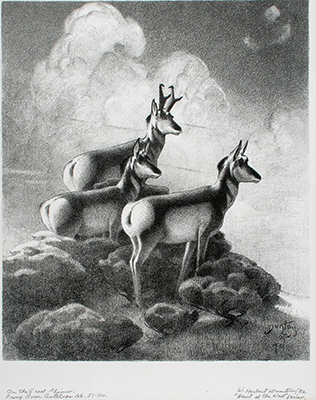

In the basement vault of the New Mexico Museum of Art, Deputy Director Michelle Roberts stands at a counter lined with paintings, prints, and sketches bequeathed to the museum this summer by Leonora Welsher, Pickard’s granddaughter. The Olive Rush watercolor, she says, “needs some TLC.” But a W. Herbert “Buck” Dunton etching of three deer? “It’s in great shape.” She points to the zig-zaggy wood-carved frame of a brilliantly moody Berninghaus oil painting, Aspens and Indians on Horseback, noting that the frame bears the artist’s nameplate. “The family had reframed it,” she says. “But magically, they kept this one and, because his nameplate is on it, we put it back on.”

Three Gene Kloss prints include a spectacular Penitente Fires, where the artist’s use of shadow conjures a sense of deep, dark velvet. A small Ernest L. Blumenschein, Sketch of the Río Grande Gorge, comes with a legend so good that it must be told, even if its truth can’t be assured: As Kathy Tenthoff, Welsher’s daughter, heard it, Blumenschein’s full painting from the sketch included a man on horseback at the bottom of the gorge. He intended the man to be himself—and painted him as a skeleton. The buyer quailed at that and asked him to paint it out. Blumenschein refused.

Welsher may have heard the story from Blumenschein himself. Her cache of 16 works, after all, were acquired in the way of all great art colonies over the years—the gifts and trades that members make among themselves. How Welsher ended up enmeshed among them traces back to her grandfather John Pickard’s plans for the Missouri Capitol. He also commissioned works by East Coast-based artists, including N.C. Wyeth, Alexander Calder, and Richard E. Miller, an internationally known portraitist with Missouri roots. But anyone who walks through the building today can get a quick lesson in the Taos artists, whose formal society lasted from 1915 to 1927.

Pickard tapped Berninghaus, Wyeth, and Miller in 1920. In January 1921, when their creations were unveiled, Pickard endured a storm of criticism about the artists’ weak commitment to historical accuracy, and endured three months of private negotiations with state leaders. Despite the unpromising start, he emerged with an enthusiastic burst of commissions for artists in Taos and elsewhere, a total of $1 million worth of them. They included wall and lunette murals by Victor Higgins, E. Irving Couse, Bert. G. Phillips, Walter Ufer, Dunton, Berninghaus, and Blumenschein. The artists earned anywhere from $1,000 to $3,500 for each piece—dear money in an era when the Taos artists could count on selling only a few paintings a year for, at best, $500 apiece.

The Taos Valley News breathlessly reported on their progress. Blumenschein had to expand his studio to fit one of the murals, and later cut a hole in the wall to get it out.

Art scholars adore the pieces, but historians to this day smirk at many of them. One Blumenschein painting depicts a meeting of Washington Irving and Kit Carson that likely never happened. And overall, the sense of comity among black people, white settlers, and Native Americans contrasted so mightily with the facts that, in 1934, Thomas Hart Benton was asked to paint a corrective in the House Lounge: The Social History of the State of Missouri. That unflinching account of everyday life included the joys and sorrows of slaves, poor people, drunkards, sleeping judges, and political scoundrels like Tom Pendergast.

Pickard, however, so liked the artists from Taos that he took his family, including daughter Caroline, there for a vacation in 1923. Three years later, he bought a house on Ledoux Street, near Blumenschein’s home and studio. Caroline was allegedly sent there for her health, although Welsher’s daughter Kathy Tenthoff says she never heard of any particular illness. Perhaps it was Caroline’s own interest in art and the spirit of the West that motivated the move. In one family photo, draped in silver and clad in velvet, she gazes with a seductive confidence at the camera. In another, she’s handsomely attired atop her horse, Shorty, which Tenthoff says she always rode with a Colt .45 strapped onto her hip.

Caroline eventually moved back East to study art, but then returned to New Mexico and continued to paint. (The donation includes two of her pieces.) Some of the works included in her collection were gifts from fellow artists upon her marriage to James Evert Culbert, a professor. With him, she lived in Taos, Las Cruces, and Santa Fe, all the while making more artist friends, including Olive Rush. Whatever talent Caroline may have had as an artist was stunted by the demands of raising a family, including young Leonora. “She didn’t paint as much after my mother was born,” Tenthoff says. “She was a housewife. They weren’t wealthy enough for her to be an artist.”

Despite that, Caroline remained friends with the Taos artists, and so when Leonora married Douglas Welsher, more gifts from them came forth. Douglas had graduated from New Mexico State University with an engineering degree, and the couple moved to New Jersey for his career. With them went works of art that to their daughter seemed “just things that Mom had hanging on the wall. They could have been something you picked up at the Five-and-Dime, for all I knew.” Hidden within them, though, was what Museum of Art Director Mary Kershaw calls “a lovely northern New Mexico story.” Beyond their connections to the Taos Society of Artists, they held one woman’s longing for the place she had left behind and a quiet yearning to finally come home.

In 2014, Kershaw took a call from Kathy Tenthoff’s husband, Ed. His mother-in-law, he said, had grown up in New Mexico and had some artworks from Southwestern artists that she hoped to donate. Kershaw said she was interested and asked him to send photos. She soon had a family reason to travel back East and included a visit to Leonora Welsher’s New Jersey home. Welsher was aging and ill, but, Kershaw says, she displayed the charm, pluck, and intelligence of a classic frontierswoman. “She was so much of this place,” Kershaw says. And so was her art.

“One of the things that is really characteristic of artist activity in northern New Mexico is the scope of community and interpersonal connections,” Kershaw says. “That direct connection between the artist and the person they gave the work to speaks to what their lives were really like.”

As her son had indicated, Welsher told Kershaw that, upon her death, she wanted the pieces to return to their true home, to New Mexico, along with a squash blossom necklace she had and a toy drum that was specially made for her by a Cochiti Pueblo artist. On June 26, 2018, she passed away; in August, the Tenthoffs carried her treasures with them on a long car drive west.

Although no undiscovered masterpieces lie within Welsher’s collection, Kershaw affirms that their value isn’t one of monetary riches but in how well they tell a tale of community and of how firmly New Mexico settles into people’s souls. The Museum of Art’s inception depended on the support of local artist communities, including the Taos Society of Artists, which girds the museum’s exhibit Good Company: Five Artist Communities in New Mexico (through March 10, 2019). Although the Welsher donation arrived too late to include any of its pieces in the exhibit, Kershaw says the fact that the gift happened during the museum’s centennial celebration underscores the highly personal, artist-to-artist relationships that marked the museum’s early years.

“The last time I saw Leonora, she made clear that she wanted to go home and that she wanted these works to go home,” Kershaw says. “What’s significant to me is what that says about the power of the Southwest. She’s lived in New Jersey for fifty-five years, in a lovely home, with a caring family. But this was home.”

“We’ve asked the gift to be associated with the family name,” Ed Tenthoff says. “It is a history, a tangible part of Americana, and more and more, every day, some of that is lost. This will keep it alive.”

When Kathy and her brother can coordinate the trip, the rest of their mother’s final wish will come true. After leaving some of her ashes with their father’s grave in New Jersey, they will bring the rest to Taos, where Caroline and James Culbert were buried so many years ago. Then, Kathy says, “My mother will finally be home.”

Kate Nelson is managing editor of New Mexico Magazine and author of the artist biography, Helen Hardin: A Straight Line Curved.