A Dazzling Denizen

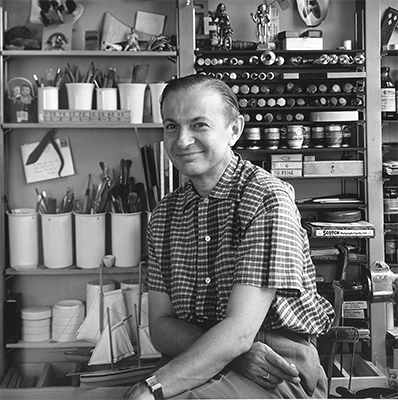

Alexander Girard made himself at home in the world, and made many worlds of his own.

Design for matchboxes of the restaurant La Fonda del Sol (detail), Alexander Girard, 1960. Alexander Girard Estate, Vitra Design Museum.

Design for matchboxes of the restaurant La Fonda del Sol (detail), Alexander Girard, 1960. Alexander Girard Estate, Vitra Design Museum.

BY JESS MULLALY

Alexander Girard might be thought of as the man at the beginning of the rainbow. As collectors, designer Alexander Girard and his wife Susan amassed over 100,000 folk art objects. The densely populated Girard Wing, which opened in 1982 at the Museum of International Folk Art, is home to a mere ten percent of their collection. Like Steve Jobs, Girard’s vision was big-picture, but he also obsessed over the tiniest of details. He was at ease as a lifelong global citizen, but chose remote, culture-steeped Santa Fe as his home. He created from the ground up, and the things that met with the favor of his curatorial eye were ever after imbued with cachet.

Born in New York City, Girard spent his childhood in Florence, Italy, before attending boarding school in England and studying architecture in London and Rome. He is most well-known as a textile designer for Herman Miller (1952–1975), contributing to the designs of Charles and Ray Eames and George Nelson.

In 1953, the same year that the Museum of International Folk art opened, Girard moved to Santa Fe from Grosse Point, Michigan. In a list sent to friends, he enthused that “1. This is the most ultra fantastically beautiful place. 2. Crystal clear, crisp air at night and early morning—you want the sun when it comes out hot. 3. Sunsets better than any postcard. 4. Fires that smell like incense.” In 1961, he presented his first project with MOIFA in the form of an exhibition called The Nativity: An International Exhibition of Folk Art Celebrating the Birth of Jesus, which traveled in 1962 to the Nelson Gallery in Kansas City.

Fifty-seven years later, another duo of museums is paying homage to Girard’s oeuvre; Germany’s Vitra Design Museum (home to Girard’s design archive and a collection of his work) is collaborating with MOIFA to present Alexander Girard: A Designer’s Universe. Though Girard worked in the last half of the twentieth century, principally in the United States, his legacy continues to grow and roam to Copenhagen, Paris, Shanghai, and Tokyo. Sometimes his legacy is tangible and Instagrammable. Sometimes it is just a remarkable memory of another time.

At the Danish textile design company Kvadrat’s showroom in Paris, a French designer who wished to be unnamed browsed through Girard fabric samples. “Ah, oui,” she said. “Alexander Girard is intemporel. Timeless. In France,” she said, “architects, furniture designers, interior decorators, all come here to choose Girard designs. They are very pointu—edgy, you might say—even though he may have created these materials maybe fifty years ago.”

“Good design like Girard’s does not go out of style,” her colleague added. “It’s like Coco Chanel’s little black dress.”

Girard’s designs lend themselves to clothing as well as furniture. In 2018, Akris, a Swiss-based global empire of more than twenty high-end fashion boutiques, presented a collection of clothing and accessories based on Girard’s innovative use of colors and patterns. During that spring and summer, Girard’s designs also inspired Akris’s window and showroom designs in Paris, New York, and Tokyo, creating a 360-degree world as saturated with his vision as MOIFA’s Girard Wing. Dresses, jackets, and pants served as canvases that sported his colorful geometric and biomorphic patterns and motifs. This fresh application of Girard’s work was hard to miss and a pleasure to see.

Akris Creative Director Albert Kriemler said through a spokesperson that Girard’s “sense of balance in everything he created is impressive.” Kriemler “interpreted” Girard’s work into a ready-to-wear collection “with the artist’s sensibility in mind.”

As he put it, “These colors are delicate yet strong, but they never scream.”

Aficionados can do more (or less) than wear Girard’s designs. Last year New York’s Museum of Modern Art’s shop featured a Girard-patterned rug, a tray, a notebook, and a coffee mug emblazoned with his Love motif, a classic Girard interpretation recognized worldwide. By Christmas, the Girard objects were sold out.

Girard also created unprecedented environments that became memorable experiences for the visitor. In 1965, Girard was commissioned to give a relatively obscure Texas airline an overhaul. Per his design, each Braniff International Airways airliner was painted a different eye-grabbing color, leading wags to call it “the jellybean fleet:” yellow, orange, turquoise, dark blue, light blue, ochre, and beige (the wings and tail remained a more traditional white).

Girard didn’t stop at the paint job. He created a typeface for Braniff’s company name and logo, and decorated the cabin interiors using Herman Miller fabrics. The ticket offices, gate areas, and Braniff’s corporate headquarters also got the Girard treatment. He also designed the sales area and lounges, furnishing them with pieces created for Braniff. This furniture was made available for sale to the public (and is collectible to this day). Just as in his own home, he incorporated folk art into the décor.

Although Braniff went out of business in 1982, Girard’s punchy palette and branding lives on in design and airline lore (not to mention on Pinterest).

His œuvre expanded to include restaurants, including the still-cooking Compound, which opened in 1966 on Canyon Road in Santa Fe, as well as the fondly remembered La Fonda del Sol, which opened in 1960 in New York City’s Time & Life Building.

The Time & Life Building was built under the chairmanship of Nelson A. Rockefeller, who for years had been deeply interested in Latin America. The same was true of Henry R. Luce, the chairman of the Time & Life publishing empire, the building’s prime tenant. The street itself, long known as Sixth Avenue, had been renamed Avenue of the Americas in a sign of solidarity at the end of World War II in 1945.

The confluence of time, place, and personalities in a new luxury building created was a moment that would usher in a spectacular Latin American-themed restaurant in the middle of Manhattan, a moment made for Alexander Girard.

As Barbara Hauss writes in the spectacular exhibition catalog Alexander Girard: A Designer’s Universe (Vitra Design Museum), “La Fonda del Sol was not merely a place to eat, but a feast for the senses, combining taste, sight, smell, sound, and touch in a fascinating and festive atmosphere.”

Girard was responsible for the big-picture elements: the name of the restaurant and its famous sun logo (which eventually became the Museum of International Folk Art’s logo), as well as thousands of other structural and decorative details. In a sentiment that resonates with New Mexico’s history, he wrote, “The sun seems a suitable common symbol familiar in all corners of this vast area, and one which played a powerful role in the great civilizations which preceded the Spanish conquistadores.”

He designed every surface (with the exception of chairs by Charles Eames), plus the linens, plates and silverware, and accents through the rooms. Never one to miss an opportunity to leave an impression, the restaurant’s logo was printed on scarves, neckties, and handkerchiefs and sold in the lobby.

Girard pioneered the open kitchen in La Fonda del Sol, making food preparation itself a part of the experience. Cooks and servers in Rudi Gernreich-designed pan-Latin outfits prepared salads and appetizers in front of entranced diners against a backdrop of a white tile wall colorfully emblazoned with the names of traditional foods and dishes and drinks in an array of typefaces. Three chefs tended a wall of huge rotisseries right in the dining area, producing roasts of beef, suckling pigs, and poultry. (It took about eighty chickens to fill one rotisserie.)

Girard also left something for future anthropologists to dwell upon: a dazzling array of matchbooks bearing various versions of the colorful La Fonda del Sol and Braniff Girard-designed logos, a reminder of a time when airplanes and restaurants enthusiastically accommodated smokers.

Textile designer Jack Lenor Larsen said, “The most important statement, more durable than the totality of the planning, the props, or the color, was the assertion that the prime concern of environmental design was how people feel in a space. This is Girard’s message and main contribution.”

It is a thought easy to contemplate on a modest scale today while spending a moment in the Girard-designed Compound restaurant in Santa Fe, perhaps after a visit to the Girard collection at the nearby Museum of International Folk Art. The restaurant’s main space is called the Rainbow Room; a large, brightly painted rainbow arcs across one white wall—perhaps a nod to Santa Fe’s sky, fertile ground for rainbows. Though rainstorms here are rare outside of summer’s monsoon season, they often produce a double rainbow. There is no open kitchen at the Compound, but in its bright, calm way, its décor contributes well to, in Lenor Larsen’s words, “how people feel in a space.” The feeling of a glass of wine or a meal with a special companion at the end of a Girard rainbow is hard to beat.

The restaurant features many other Girard touches, from hallway ceiling tiles covered in Navajo rug squares, creating an elegant patchwork quilt effect, to the sunken bar, a conversation pit iteration that has aged well. One large nicho shelters a collection of miniature Peruvian figures.

Santa Fe denizens may be forgiven for taking the Compound for granted—in the same way Parisians take the Eiffel Tower in stride. It’s one of the finest restaurants in the City Different, but it’s also a rare temple of Girardiana, of an œuvre that splashily spans time, continents, genres, and cultures, with no sign of slowing down. The late designer’s love for Santa Fe is a fond imprimatur that takes many forms, ever-burnishing the city with the warmth of that iconic Girardian sun.

Jess Mullaly writes about art and design for various publications.