On Display in Santa Fe (Part II)

Exhibition designs inspired by art, ethnology and burlesque

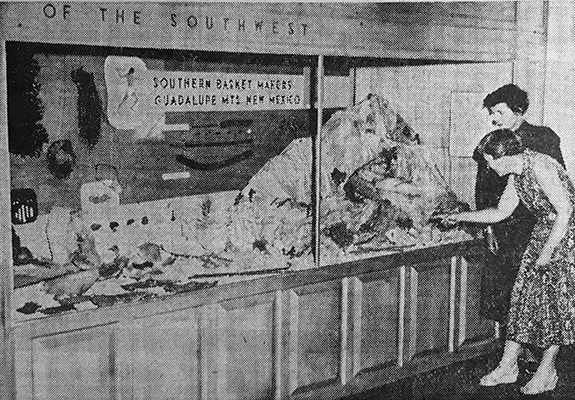

Grade school students viewing an early exhibition at the Museum of International Folk Art, 1954. Courtesy Bartlett Library and Archives Collection, Museum of International Folk Art.

Grade school students viewing an early exhibition at the Museum of International Folk Art, 1954. Courtesy Bartlett Library and Archives Collection, Museum of International Folk Art.

BY DAVID ROHR

(You can read Part 1 here).

On a warm evening in August of 1917, a group of prominent painters gathered for an informal meeting at the Santa Fe home of Dr. Edgar Lee Hewett.

As director of the Museum of New Mexico, Hewett had welcomed these artists to provide guidance for the upcoming exhibitions in the new art museum, scheduled to open in November. The Albuquerque Journal reported that “Robert Henri, Mr. and Mrs. Henderson and others present took part in an animated discussion of art principles and of methods and rules that should govern exhibits.” Several in the party were newcomers to the city. Henri, a central figure in the Ashcan School movement, had recently arrived in Santa Fe at the invitation of Hewett. Chicago painter William Penhallow Henderson had moved here in 1916 along with his wife, Alice Corbin Henderson, who had been receiving treatment at Sunmount Sanitorium.

The idea that Hewett would meet with these esteemed painters to discuss art principles would have seemed unlikely a decade earlier. After all, he was strictly a man of science—not an artist. Staging art exhibitions had never been part of Hewett’s plan when he co-founded the Museum of New Mexico in 1909. His original goal was to establish an museum of archaeology in the Palace of the Governors that would complement the mission of American School of Archaeology. However, once the museum had opened, he quickly recognized that new synergies might be possible by cultivating artists of the emerging Southwest art movement in New Mexico. Hewett, along with the museum’s Board of Regents, began to envision an institution that exhibited both art and archaeology.

The Museum of New Mexico hosted the first art exhibitions in the west end of the Palace of the Governors with work by painters Warren Rollins, Gerald Cassidy, Carlos Vierra, and others working in the Santa Fe and Taos schools. Cassidy’s now-iconic painting Cui Bono? made its Santa Fe debut here in January of 1912. Between 1911 to 1917, Hewett regularly hosted art exhibitions in the Palace to great acclaim. With an ever-increasing roster of artists, by 1914 it was clear that the intimate galleries of the Palace were too small to adequately showcase the painters of the New Mexico art scene. As a result, Hewett, along with regent and patron Frank Springer, successfully lobbied the legislature in 1915 for funds to build a dedicated art museum.

By the late summer of 1917, the construction phase was nearly complete and Hewett and company began to focus on the content and design of the opening exhibits. Henri and Henderson, along with other artist advisors, agreed that they wanted to present a major exhibition that would be taken seriously by art critics but also “delight art lovers and artists.” They concluded that they should “make an exhibit of big pictures well hung … rather than a crowded show with many mediocre pictures overshadowing the finer and better work.”

The New Mexico Art Museum was a large, austere exhibition venue. Spacious alcoves permitted paintings to be hung in orderly rows instead of the stacked salon-style arrangement often necessary in the Palace of the Governors. The alcoves incorporated three levels of built-in hanging tracks to allow paintings to be securely displayed in a variety of arrangements.

The grand opening exhibition was a resounding success, featuring work from over one hundred Santa Fe and Taos artists. It established the new art museum’s reputation as the center of the emerging Southwestern art scene, and helped form the basis of a permanent collection. Many exhibitions, large and small, were now presented on a regular basis, showcasing work from New Mexico and eventually from around the world.

Palace Exhibitions after 1917

The opening of the Art Museum effectively ended the era of art exhibitions in the Palace of the Governors. From 1918 through the 1960s, the west Palace galleries presented items of archaeological interest. The large west room was designated as the Hall of Archaeology and populated with standardized wooden display cases and dioramas. These cases and dioramas would come to define the Palace exhibit aesthetic until the mid-1950s. On the east end of the Palace, the old historical exhibits remained much the same through until the early 1930s, when changing leadership in the New Mexico Historical Society granted Hewett and his staff oversight of those collections.

The Forgotten Exhibition

By the late 1930s, the museum was ready to expand its curatorial scope and develop Native American ethnology exhibits. As additional space would be needed to make this possible, Hewett took the opportunity to acquire the former National Guard Armory Building in 1938, conveniently located behind the Palace on Washington Avenue. Built in 1909, the old armory had served for years as a vibrant community center, hosting high school basketball games and popular Saturday night dances when not in use by the National Guard.

Hewett assigned Bertha Dutton [see “They Also Dug” on page 50], the museum’s newly appointed curator of ethnology, to lead the team that would turn the armory into a museum space. In a field dominated by men, Dutton had the distinction of being one of the few female curators in the country at that time. Dedicated and methodical in her approach, Dutton spent the first two years of the project organizing storage and research areas in the armory’s basement. When the installation phase began in 1940, Dutton assembled a team of ten to design and produce every aspect of the exhibition, including research, casework construction, graphics, cartography, and diorama building. By the summer of 1941, the team had converted the armory into a spacious and orderly exhibit gallery. Designated as the Hall of Ethnology, it presented a collection of exhibitions on the contemporary “arts and crafts” of Pueblo, Navajo, and Apache peoples of the Southwest.

The Hall’s new exhibitions were more advanced than those in the Palace of the Governors, not only in appearance, but also in how they accommodated the visitor. Dutton explained her approach: “[Museum attendants] have come to realize that individuals can absorb only about so much of anything at a time—be it culture, education, entertainment, food, or drink. When a person comes into a museum—usually tired and always in a hurry—even with the best intentions in the world, he can see and absorb only a limited amount of what is displayed before him. Therefore, a scheme was worked out for presenting the different phases of Indian arts and industries in separate alcoves. By this plan, a limited number of items can illustrate each class of material.”

With its high ceilings and spacious interior, the transformed armory building was an ideal museum space. Large vertical wood and glass cases contained nine separate alcoves, each fitted with electric lighting to illuminate the objects within. Section cases were plainly yet prominently labeled. Six dioramas filled the central area of the gallery, and Navajo and Pueblo paintings lined the walls.

The Hall of Ethnology continued operations until about 1981, when both the space and its exhibitions were no longer viable. Part of its mission was later assumed by the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, which opened in 1987 on Museum Hill. The building itself was razed in the early 2000s in order to build the New Mexico History Museum. The Hall of Ethnology is all but forgotten today, but it stood for nearly forty years as a vital part of Santa Fe’s museum landscape.

Striptease-Inspired

When the Museum of International Folk Art opened its doors in November 1953, it marked a radical change in design for the Museum of New Mexico. An intentional attempt to break from the past, the inaugural exhibition combined unusual materials, novel arrangements, and contemporary design concepts to present an exhibition unlike any seen before in Santa Fe. The Costume Parade was the centerpiece of the new gallery—an elevated island-like structure populated with abstract wooden mannequins clothed in colorful folk costumes from around the world. This platform was surrounded by a curved railing and a “moat” of gravel around the perimeter. Codesigners Bruce Inverarity and Stanley Nelson modeled it after a famous New York City burlesque stage with an elevated ramp that allowed performers to parade into the audience.

Visually, the new exhibition gallery was a breath of fresh air. Absent were the old-style dark wood and glass display cases used in the Palace of the Governors. Inverarity told The Santa Fe New Mexican that the new gallery was “a deliberate departure from the stodgy arrangement of exhibit cases which is an almost traditional characteristic of many museums.” The designers also avoided glass cases, as they were thought to create a “psychological barrier between the exhibit and onlooker.” Inverarity and Nelson also considered how visitors would navigate the space, arranging cases in “an irregular manner” to allow for “better freedom of movement while browsing.”

Inverarity echoed Bertha Dutton’s earlier preference for simplicity in exhibitions. “I do not believe the display cases should be used as storage area. We want people to feel they are looking at a single item instead of an indistinguishable mass.” Visitors appreciated this new design direction, which raised the bar and eventually influenced future presentations within the entire Museum of New Mexico system.

Mid-Century Design

The contemporary design of the Costume Parade was ahead of its time, or at least for Santa Fe museums. In the old Palace of the Governors, the small exhibits of the 1950s were bound by more traditional thinking. This was evident in the post-World War II installations in the Hall of Archaeology. Marjorie Lambert, curator of archaeology, along with preparator Marybelle Spencer, designed and installed several new shadowbox-style exhibit cases in the west room of the Palace between 1955 and 1960. The appearance of the new exhibits adhered to design conventions of the time: busy arrangements of artifacts behind glass. Each section title was set in all capitals with a Futura-style typeface, which gave the displays a distinctive mid-century science fair appearance. While not particularly elegant by

today’s standards, the exhibits were educational and quite popular, providing context for the objects on display.

It took years for the rest of the system to catch up with the more open design approach introduced by the Museum of International Folk Art, but the other museums did eventually evolve. New trends in design began to take hold in the 1960s and 1970s, as exhibitions in the Palace of the Governors began to turn away from the topic of archaeology and focus fully on New Mexico history using more immersive presentation styles.

Professionalization

Starting in the 1960s, the Museum of New Mexico began to reconsider its exhibition development methods. By July 1964, director Delmar Kolb had established a unified Department of Exhibitions (now Exhibit Services) to serve the state museums in Santa Fe with a full team of designers and craftsmen. Curators no longer had to develop exhibitions on their own; they were paired with trained designers, hired for their creative talent and outside experience. The consolidation provided each of the museums with the benefit of the same pool of exhibition expertise.

The 1970s brought more change. To better visualize their concepts, exhibition designers started to construct small-scale foam board models. New font technology allowed for richer label typography and custom title walls. Designers now paid closer attention to lighting and color choices. Modern conservation practices ensured that objects and artwork were handled properly under conditions that would keep them safe and stable while on exhibit. By the late-1990s, computers and digital technology had transformed the design process.

In 2019, exhibition designers in Santa Fe continue to be influenced by the ideas, innovations, and experiences of their talented predecessors from the past century. They work closely with curators to tell compelling stories and create meaningful visitor experiences. Just as it was in Hewett’s parlor back in 1917, today’s designers still engage in “animated discussions of methods and rules that should govern exhibits.” Most importantly, the goals of educating and engaging museum visitors continue to spur design excellence and innovation in the Museum of New Mexico system.

On Exhibit: Designs That Defined the Museum of New Mexico is on display in the New Mexico History Museum through July 28, 2019.

David Rohr is the director of the Museum Resources Division and Exhibit Services in the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs, and art director of El Palacio. He is the curator of On Exhibit: Designs That Defined the Museum of New Mexico.