The Right to Remember

Indigenous artists rebuild in post-conflict Peru

BY EMILY WITHNALL

In 1990, at the height of Peru’s war, Wari Zárate and other artists in the Andes began to teach art to children orphaned by the war. The artists thought it might be a way to help the children cope with the bloodshed they had witnessed. As the children learned traditional crafts like ceramics and retablo-making, they began to shape their losses into artistic narratives. For the children and their teachers, art was a way to express their reality—a critical act in the face of a government that continues to want them to forget.

In Zárate’s Encuentro de Conciencias (Meeting of Consciences), a mixed media painting, two large panels depict robed figures facing one another. Each figure’s head is a skull with narrowed eyes and bared teeth. The figure on the left is robed in red—the color of Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path), the guerilla terrorist group that formed in the 1970s in the Ayacucho region of the Peruvian Andes. The figure in the right-hand panel is robed in green—the color of the Peruvian military. In both panels, the colors of the robes gradually transform into a deep blue dotted with black crosses. The crosses symbolize the nearly 70,000 disappearances and deaths that resulted from the Shining Path civil war in the 1980s and 1990s.

Two outer panels frame the robed skulls. Large, stylized black crosses on top of red and green backgrounds, respectively, appear between miniature retablos. From afar, the retablos appear to depict scenes of humans in mountainous landscapes. The figurines inside each box are shiny, colorful, and less than an inch tall. Their miniature size and vibrant colors invite the viewer in for a closer look, and deliver an unexpected and sobering surprise.

The forms of torture and killing that the military preferred are depicted on the right. One scene reveals human figures being stuffed into a large oven as an armed, masked man stands guard. Another retablo depicts a man dangling upside-down below a military helicopter. On the left, the retablos depict Sendero Luminoso’s preferred terrorizing strategies. In one scene, an insurgent drowns a woman in a waterfall. Another reveals people being decapitated in the mountains.

Encuentro de Conciencias is one of the pieces located in the Memory Museum portion of the Crafting Memory: The Art of Community in Peru exhibit at the Museum of International Folk Art (MOIFA). Amy Groleau, an anthropologist, archaeologist, and the curator of Latin American Collections at MOIFA, says Zárate’s piece speaks to the way Indigenous people in the Andes were caught between Sendero Luminoso and the military during Peru’s civil war.

“There wasn’t a way to be neutral,” Groleau says. “Each group suspected you to be collaborating with the other.”

Peru’s Shining Path War took place from 1980 to 2000 and was perhaps the most grisly civil war in Latin American history. Not only did the human toll in Peru rank among the deaths and disappearances occurring elsewhere across Central and South America; both the military and Sendero Luminoso contributed equally to the war’s brutality. In other countries, military violence far outweighed guerilla violence, but in Peru, Sendero’s organized terrorist tactics delivered nearly equal amounts of damage.

“Think Khmer Rouge,” says Peruvian scholar Jo-Marie Burt, who is professor of political science and Latin American studies at George Mason University, and is the author of Political Violence and the Authoritarian State in Peru: Silencing Civil Society. “Sendero felt that the state and everything associated with it needed to be wiped off the planet.”

Sendero Luminoso began in the Andes in Ayacucho, a region of Peru inhabited by Indigenous Quechua-speaking people. The people in this impoverished region had no representation in Peru’s Spanish-speaking government. In part, Sendero began as a bid for decision-making power and greater access to resources. But their tactics—informed by a blend of Maoism, Marxism, and Leninism—consisted of intimidation, torture, and killing. They demanded total allegiance, and murdered people suspected of opposing them.

The military, in an attempt to suppress Sendero Luminoso, responded in kind. Gathering intelligence from villagers was nearly impossible because few soldiers could speak Quechua. What began as a reign of terror by Sendero became a full-fledged “river of blood”—just the scenario Sendero’s leader, Abimael Guzmán, said the insurgents would have to endure to achieve their goals. The conflict pitted indigenous people against each other. No one knew whom to trust. Sendero insurgents severed phone lines to cut off communication, and both sides killed journalists seeking information. Although Indigenous peoples make up only sixteen percent of Peru’s population, by the end of the war Indigenous peoples made up almost eighty percent of the 70,000 fatalities.

As disappearances ballooned, women in Ayacucho began to visit military barracks and police stations to try to find out what happened to disappeared family members. In 1983, they formed the first human rights group in Peru: the National Association of Relatives of the Kidnapped, Detained and Disappeared of Peru (ANFASEP). Inspired by the Argentinean Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, ANFASEP marched to draw attention to the disappearances. Sendero was known to be anti-church, so the women of ANFASEP marched with a large black cross with NO MATAR (DON’T KILL) written across it to show that they were not terrorists.

The women of ANFASEP also began to feed children orphaned by the war. Assisted by Centro del Culturas Indigenas de Peru (CHIRAPAQ), they built a dining hall and regularly fed over 300 children. In addition, the two organizations began to instruct the orphans in traditional arts, like retablo-making.

Older retablos depicting agrarian scenes are on display at the Crafting Memory exhibition at MOIFA, along with retablos depicting scenes from the civil war.

In 2000, following the brutal dictatorship of Alberto Fujimori and the fall of Sendero’s leader, Guzmán, the war came to an end. As mass graves began to be exhumed, ANFASEP began to assemble items from missing loved ones. In 2004, they opened El Museo de la Memoria (Museum of Memory) “Para Que No Se Repita” (“So That History Doesn’t Repeat Itself”). In the small, three-room museum in Ayacucho, ANFASEP displays personal effects and photos of the disappeared, newspaper articles about the conflict, and a timeline of the war and of ANFASEP ’ s beginnings. They also display a range of visual art depicting the horrors the artists witnessed. Encuentro de Conciencias is part of the museum’s permanent exhibition. Like Zárate’s painting, the art and information available in the Museum of Memory demonstrates the complexity of the war and the devastating consequences of the violence.

In putting together MOIFA ’ s Crafting Memory exhibition, Groleau wanted to replicate the way the story of the war is told in Ayacucho’s museum. “I wanted to show that this is self-representation,” Groleau says. “This is how they are representing themselves in their own museum.” Still, with a war as complex as Peru’s, she admits that it’s impossible to represent all the intricacies of the conflict in such a small space. “I tried to focus on art’s role, both during the conflict and post-conflict in working through trauma.”

MOIFA’s exhibition title, Crafting Memory, suggests an act of creation. “It’s helping to create that collective memory,” says Groleau. “Public testimony has been really important for people to know they’re not alone, and for people to know that these are shared experiences that can start to form this new consciousness.”

The second part of the title, The Art of Community in Peru, refers to the way making art can bring people together, especially when such art is seen to be subversive. Although Andean artists began to make art as an act of self-expression, the military and government officials often find these visual responses to be contentious. Continuing to make art in the face of intimidation is an act of resistance and resilience.

“There’s a lot of disagreement about how or whether to remember,” Groleau says. “There are people currently in politics now who have a stake in forgetting.”

Groleau is referring to members of Peru’s government, many of whom also served the government during the war. Government officials are quick to label citizens as terrorists if their art or narratives implicate the military’s violent role in the conflict. When the independent Truth and Reconciliation Commission issued a 5,000-page report in 2003 that found the military to be equally as responsible for the 70,000 deaths and disappearances as Sendero, many government officials rejected this conclusion. In their eyes, soldiers were the heroes who saved the country from the terrors of Sendero.

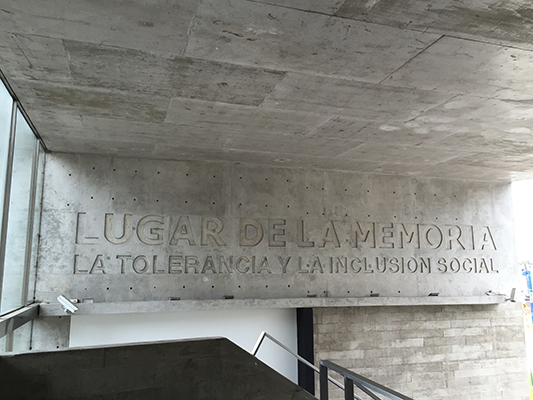

As a result, Lugar de la Memoria, la Tolerancia y la Inclusión Social (The Place of Memory, Tolerance, and Social Inclusion), located in Lima, tells a different story than ANFASEP’s museum. Lima’ s government-run museum features exhibits that primarily demonstrate the atrocities committed by Sendero.

“The military produced their own report in response to the Truth Commission,” Burt says. The Peruvian military’s report does not acknowledge their role in the violence or take responsibility for any of the government’s atrocities.

“A military that wants to forget is not going to write a response. They just want you to remember what they want you to remember,” says Burt. “They don’t apologize; they only talk about killings and rapes in terms of ‘excesses.’ Their stake is in creating a narrative that makes you believe that Peru was saved due to Fujimori’ s iron-fisted policies.”

Still, the museum in Lima includes victims’ narratives, and as both Burt and Groleau point out, this is an important step in the right direction. “It’s amazing that Peru has a national museum focusing on the armed conflict, a space where victims and people can go to learn about what happened,” Burt says. “I believe it’s possible that as time goes on, the contents of this museum may shift.”

Despite her misgivings about the way Lima’s museum tells the story of the war, she also recognizes that it’s still an important space. “Victims are in the process of trying to claim it as their own and remake it into something that is meaningful for them.”

Groleau reiterates that it’s important for Peruvian artists to keep telling their stories. The war ended just seventeen years ago and the wounds are still fresh. “It’s beautiful to see people turning toward their own cultural heritage to search for justice and to tell truths,” Groleau says. “Even if you don’t know what happened to the person you loved, you can say, ‘We endured all of these things trying to find out.’”

In Peru, stark divisions between classes and races can make memory a battleground. Artists who tell their stories are resisting attempts by the government to erase their history—a silencing that serves to perpetuate the violence they have already experienced. Making art constitutes “a stubborn refusal to accept the violence to which they and their loved ones were subjected for so many years,” Burt says. “They are asserting their voices and saying, ‘We too are citizens of this nation. We too have rights. You can’t erase us.’”

Although Crafting Memory has been in the works for years, the timing of the exhibition’s opening is serendipitous because it touches on subjects that people in the U.S. have been grappling with. “We have a tough time talking about race, class, difference, inequality, what the causes are, what the solutions are, ourselves,” Groleau says.

She is quick to acknowledge that there is no true comparison between the scale of violence in the U.S. and the kind of violence Indigenous people in the Andes experienced. Still, Groleau sees parallels in economic exclusion, the lack of political representation for many people, and the inability of those with the most power or resources to truly empathize with the ways marginalized populations struggle. In some ways, Peru’s civil war is a cautionary tale. But what Groleau sees as being most important is the groundswell of people who do not have a lot of power making their voices and stories heard. “They are using art to build solidarity, to find common issues, to say ‘Your issue is my issue.’”

Emily Withnall, born and raised in New Mexico, currently lives in Missoula, Montana, where she works as a poetry instructor and freelance writer.

In conjunction with Crafting Memory, MOIFA’s Gallery of Conscience debuts Community through Making: From Peru to New Mexico on January 6, 2019, from 1–4 p.m. Enjoy artist talks, a pop-up market, and art-making activities.