The Captive

The true story of an Apache daughter, wife, mother, and slave who risked everything to be free

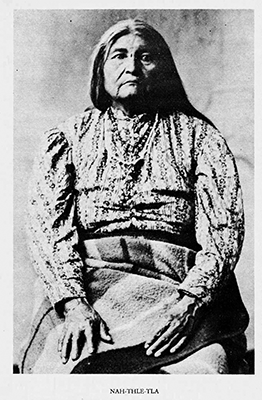

Na‐thle‐tla. Photograph from I Fought with Geronimo by Jason Betzinez, published by the Stackpole Company in 1959. Betzinez was Na‐thle‐tla’s son.

Na‐thle‐tla. Photograph from I Fought with Geronimo by Jason Betzinez, published by the Stackpole Company in 1959. Betzinez was Na‐thle‐tla’s son.

BY PAUL ANDREW HUTTON

The Mexican soldiers came late in the Spring of 1855.

The people saw them in the distance but thought they must be their own Bedonkohe men returning from a raid deep into Mexico. The rancheria in the Animas Mountains in New Mexico’s bootheel, far south of the Bedonkohe homeland, was well north of the line the Americans thought so important—the line that divided them from Mexico. No Mexican soldier dared to cross that line, so the people knew that they were safe from attack. Mangas Coloradas had been careful to keep the peace with the Americans. So the women and children and old men busied themselves with preparations for the feast and dance to celebrate the return of their warriors.

Nah-thle-tla and her two children were staying with her husband’s parents while he was off on the raid into Mexico. By the time she realized that the distant riders were soldiers from Chihuahua, it was too late. The Mexicans rode through the camp shooting at anything that moved. No warriors were in the rancheria, and the few old men and boys had no guns. It was over quickly. Nah-thle-tla and her children were among the survivors.

As they rounded up the surviving Apache women and children, the soldiers set fire to the wikiups and all the people’s belongings. They saved only some dried venison to feed the captives. Knowing that the smoke from the burning village would attract other Apaches, the Mexican commander mounted the captives on mules and hurried them south. Nah-thle-tla was surprised at how well the Mexican soldier chief treated his prisoners. One woman, however, dared to berate him and boast of the many Mexicans killed by her husband. For her pride she was allowed to walk over one hundred miles to Casas Grandes while all the other captives rode.

Upon reaching Casas Grandes, the soldiers rested for two days. Then they loaded the prisoners onto primitive two-wheeled carts and hauled them to Galeana and then along the Santa Maria River to Namiquipa. This was the very village recently attacked by the war party from their rancheria. The enraged villagers demanded that the Apache prisoners be turned over to them, but the Mexican officer refused. As he hurried his column onward to Chihuahua City, the angry mob cursed the Apaches and hurled stones at them.

At Chihuahua City, the captives were separated and sent to live with various Mexican families. Nah-thle-tla’s children were taken from her. She never saw them again. This had been the heartbreaking fate of so many Apache families at the hands of first the Spanish and then the Mexicans. The Southwestern slave trade—both a cause and consequence of the long war between the Apaches and Mexico—took a ghastly human toll, with thousands of Apache men, women and children sold into slavery in Mexico, Cuba, and other Spanish colonies.

The family Nah-thle-tla was placed with treated her well. She learned domestic chores and even accompanied the family on walks through the city. She did not know it, but she was being groomed to be a house slave.

Nah-thle-tla, like the famous Geronimo (then called Goyahkla), was the grandchild of the revered Bedonkohe Chief Mahco. She and the great warrior grew up together in New Mexico’s Mogollon Mountains near the headwaters of the Gila River. She always remembered that she and Geronimo were nine or ten on the Night the Stars Fell. This majestic 1832 meteor shower terrified people all across North America. Three years later, it was followed by the equally awesome appearance of Halley’s Comet. The Apaches understood both these events to portend great changes to come.

Not long after the comet flashed across the sky, a young Nednhi from Mexico’s Sierra Madre came to visit. His name was Juh, and even in young manhood he was already a giant among the Apaches at over six feet tall. He stuttered badly, and some said that was the origin of his name. Many years later, a California newspaper reporter, agonizing over the pronunciation of his name, wrote: “If Ju (or Juh) would kindly inform the press how he spells his name, he would have the satisfaction of knowing that when he dies on the field of glory, he would not be orthographically mangled in the dispatches.” The Bedonkohes looked down on their southern cousins, regarding them, said one warrior, as “outlaws recruited from other bands, and included in their membership a few Navajos as well as Mexicans and whites who had been captured while children.” They seemed devoted entirely to raiding and warfare.

Juh was fun-loving and full of mischief. When the Bedonkohe girls went into the mountains to gather acorns, Juh and other Nednhi boys would ambush them on their way back to the village and steal their baskets of nuts. Among the victims were Nah-thle-tla and her cousin Ishton. Geronimo’s grandmother told him to go and thrash Juh to stop him from tormenting the girls. Geronimo did as ordered, but in time Juh married his beautiful cousin Ishton, became his warmest friend and ally, and rode with him on countless raids against both the Mexicans and the Americans.

Nah-thle-tla fell in love at about the same time as Ishton. The young warrior Shnowin had met her gaze many times, but was too bashful to speak to her. He spent his time singing love songs until his father took pity on him and approached Nah-thle-tla’s parents with an attractive offer of ponies to seal the bargain. Even after the marriage was arranged by the parents, the young lovers were kept apart to protect the bride’s reputation. Four days of feasting followed, and then at sunset the ceremony was finished. The young couple’s parents proclaimed their children’s marriage to all the people. This was a happy union, and within two years they had two children.

Shnowin and several other Bedonkohe warriors joined Juh and his Nednhi band on that fateful raid far into Mexico against the village of Namiquipa to the south of Casas Grandes. Geronimo had been wounded by Mexican soldiers in a previous raid, and did not go with Shnowin. In this raid, the Mexicans were defeated on the Santa Maria River, but at great cost; Shnowin and several other warriors were killed.

Nah-thle-tla did not yet know she was a widow. After her training period in Chihuahua, she was sold to a wealthy Hispanic merchant from Santa Fe. The merchant loaded her into an oxcart along with another young Apache woman. The cart, pulled by four oxen and with a large, menacing dog tied alongside, was webbed with rope to form a cage. The merchant slowly followed the ancient Camino Real to El Paso and then moved up the Rio Grande to Albuquerque and Santa Fe with his human cargo.

As they recognized the country of the Warm Springs Apaches in the distance, the young woman began to sob. “What are you crying for?” Nah-thle-tla asked. “Don’t you know that we are close to our homeland, that if we should manage to escape we would find our own people?” The women carefully studied the countryside for landmarks as the oxen slowly plodded northward.

Once they finally reached Santa Fe, they were sent to serve in the homes of different families. Nah-thle-tla worked hard for her master. She learned to grind corn to make tortillas, to cook in the manner of the household, and did all the family laundry. She was treated kindly, shared in all the family meals, and was allowed considerable freedom around the hacienda grounds. Still, she longed for home and carefully plotted her escape.

The master of the household left on business, and while he was gone the young people threw a grand fandango. They danced and drank well into the night and finally, when Nah-thle-tla was certain all were sound asleep, she wrapped food, a knife, and a coil of rope in a knapsack and crept out a window. After climbing along the wall of the hacienda, she lowered herself to the ground and fled Santa Fe.

It was dawn by the time she reached the outskirts of the town and hid herself amidst the brush to wait for the night. When darkness returned, she headed toward the nearest mountains. Since she was east of the Rio Grande, the mountains did not form a continuous range, and she was sometimes exposed on the open prairie. She hid during the day, and while some vaqueros came near, she was not seen. When she reached the Sandia Mountains she felt it safe to travel during the day.

She traversed rough country. After several days her knapsack was empty and she fed herself on piñon nuts, berries, and various seeds. She fretted over the bears that lived in these mountains and sought the same food. She had only a butcher knife for defense. Apaches never hunted bears; there was a strong taboo against killing bears, for they were the ancestors of the people. But, if attacked, a warrior also could not back away. The meat of the bear was never eaten, although the claws might be carried away to make a trophy necklace, and the paw used in healing ceremonies. If an Apache encountered a bear, they would say, “Go away, Grandpa!” (Not surprisingly, this often did not work, and many women and children were mauled while gathering berries or piñon nuts.) Every Apache band had tales of bear encounters. Some Apaches feared bears as much as owls, for they believed that wicked people returned to earth as bears.

One day she came upon the tracks of a large bear at a mountain watering hole and discovered the rocks still wet from where he drank. She hurried on to find another place to drink.

She remembered how Chief Loco, the leader of her Warm Springs people, had once fought a silvertip grizzly bear with only a butcher knife, and how the bear had lacerated his cheek and neck and had almost torn out his eye.

Nah-thle-tla was young and strong, but after nine days of climbing up and down mountain canyons, she was tired. It was then that she came to the top of a ridge and, far to the southwest, saw the clear outline of the Magdalena Mountains. These were the mountains of her homeland. She sat down and wept.

As the sun set, she made her way down out of the Manzano Mountains and found herself near Isleta Pueblo. She made it to the Rio Grande before sunset, but feared to cross since she did not know how deep the water was. She hid herself, and the next day watched several people wade across the river. After dark she hurried into the cool waters of the river, which came to her armpits at the deepest point, and waded across. Once across she found a pony grazing in a cornfield. She made a bridle from the rope she had carried with her and was soon riding southwestward toward the mountains.

On the third day after crossing the river, Nah-thle-tla rested her pony on a hilltop. In the distance she saw three men walking just below her. She could see by their clothing that they were Apaches and so she called out to them. They promptly scattered, for using women as decoys was an old Navajo trick. She continued to call out to them, telling them who she was and that she had just escaped from the Mexicans. (The citizenship change that resulted from the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was lost on the Apaches—a Mexican was a Mexican no matter what side of the Rio Grande they lived on. This sentiment was shared by most of their new American neighbors as well.)

The three men cautiously approached, and she cried out with joy as she recognized Loco, the chief of her own band of Warm Springs Apaches. He told her that his rancheria was not far, and that several of her relatives were there. In the camp she found her mother. They shared a joyful reunion mixed with much grief. She now learned of the death of her husband. She told her mother of the sad loss of the children. There was always the hope that they might yet escape and return home, but that was not to be.

Two years later Nah-thle-tla married Tudeevia, son of the former chief of the Warm Springs Apaches. His father had died when he was still a child, and so the people had chosen Loco and Victorio to be dual chiefs of the band. There followed a period of peace for the Warm Springs people as the United States government established an agency for them at Ojo Caliente. The hot springs were a popular place, and the nearby Black Mountains provided abundant game for the men as well as the plants, nuts, and berries that the women gathered. The streams were flush with trout, but the Apaches touched nothing that lived under the water.

In 1860 Nah-thle-tla gave birth to a son (who would relate her captivity story in his classic 1959 memoir I Fought with Geronimo), and two years later to a daughter. That year, 1860, also marked a moment of great change for all the Apaches, as the kidnapping of a young boy later to be known as Mickey Free set in motion the outbreak of war with the Americans.

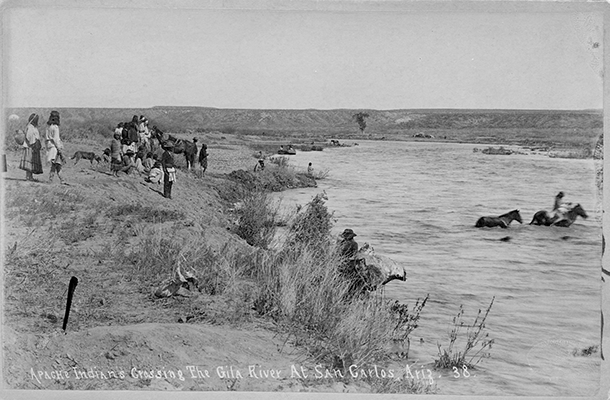

In 1877, the American government forced the Warm Springs people to relocate to San Carlos in southern Arizona. Although Loco attempted to keep the peace, Victorio brooded over this treachery and soon led his people off the reservation and into long years of war and suffering. After Victorio’s 1880 death at Tres Castillos in Mexico, Geronimo assumed leadership of the final resistance. After he surrendered in 1886, all the Chiricahuas were imprisoned, first in Florida, then Alabama, and finally at Fort Sill, Indian Territory (Oklahoma). They were all held as prisoners of war at Fort Sill—men, women, and children—until after Geronimo’s death in 1909. In 1913, the Chricahua bands divided, with some relocating to the Mescalero reservation in New Mexico while others took land allotments around Fort Sill.

It was to be just as the falling stars had portended. Nah-thle-tla would live to see it all, for she did not die until 1935, when she had reached 112 years of age.

Paul Andrew Hutton is a distinguished professor of American history at the University of New Mexico. His latest book, The Apache Wars, was published by Crown in 2016.

Lifeways of the Southern Athabaskans, an exhibition featuring cultural objects that represent the lifeways of different Apachean groups, is on view at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture through June 2, 2019.