On display in Santa Fe (Part I)

How the Palace of the Governors became a museum

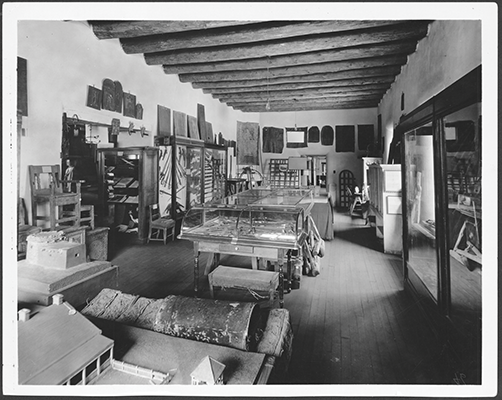

Exhibition Room of the Historical Society of New Mexico, Palace of the Governors, ca. 1924. Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), Neg. No. 053554.

Exhibition Room of the Historical Society of New Mexico, Palace of the Governors, ca. 1924. Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), Neg. No. 053554.

BY DAVID ROHR

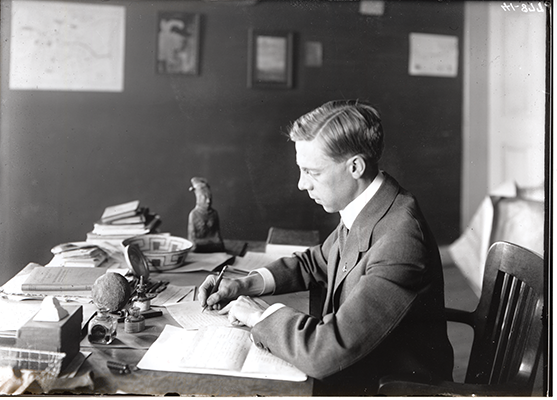

Sylvanus Morley was starting to worry. It was November 1912—only days away from the public unveiling of his new exhibition, New-Old Santa Fe, located in the historic Palace of the Governors.

As curator, he feared that the staff might not finish installation in time for the scheduled opening date.

A lot was riding on the success of this exhibition.He, along with several other civic leaders, had been passionately advocating for Santa Fe builders to embrace a locally relevant architectural style. Promoted as “Pueblo Revival” or “Santa Fe Style,” it was an effort to retain and promote the unique adobe building style that had characterized the city for centuries. Many of the old structures were being rapidly replaced by contemporary architectural designs popular in eastern cities, that, in New Mexico, had no authentic sense of place. Morley argued that building in the Pueblo Revival style would retain Santa Fe’s unique historical charm and serve as a draw for tourists and economic development.

Despite Morley’s concerns, installation was moving along, conducted by a small crew from the Museum of New Mexico, an institution that had been established only three years earlier in 1909. The museum was based in the old Palace of the Governors, remodeled to display artifacts excavated by the School of American Archaeology (now School for Advanced Research). Director Edgar Lee Hewett, an archaeologist and a savvy civic promoter, soundly endorsed the New-Old Santa Fe exhibition, recognizing that the museum could serve broader interests.

To support Morley’s effort, fellow museum employee Jesse Nusbaum was tasked with conducting a photographic survey of old Santa Fe architecture. He would capture examples of adobe construction from around the city, with the best photographs included in the exhibition. Nusbaum, who was also the foreman for the installation, had observed Morley’s agitation in the days leading up to the opening: “Once this work of preparation got under way, Morley was periodically hovering about us, fretting and fuming for fear everything would not be fully completed and installed for the formal opening on November 18, 1912. Every few days he would come up with new suggestions for added features and exhibits.” Morley had reason to worry. The exhibition was his best chance to shape public opinion in favor of this new architectural direction. He realized that if the effort failed, Santa Fe could soon look no different than any other small city in the country. For the Santa Fe Style to prevail, the exhibition had to succeed. The clock was ticking.

Fast forward 106 years to the present. Looking back over the past century, the Museum of New Mexico has grown to include four major museums in Santa Fe along with seven historic sites around the state. Thousands of exhibitions have come and gone since Morley’s 1912 effort. Down the block from the Palace of the Governors on Lincoln Avenue, a team of artists and craftsmen recently completed preparations for yet another exhibition. This time, the topic is not architecture or archaeology. Instead, it is an exhibition about exhibitions.

On Exhibit: Designs That Defined the Museum of New Mexico looks back on major exhibition design milestones within the venerable state museum system. On Exhibit highlights many important and noteworthy exhibitions staged over the years, from the 1880s up until the present day. It reveals how design concepts changed over time, evolving to better educate and engage visitors. A mix of photographs, historical news clippings, constructed vignettes, and video interviews combine to tell the story of Santa Fe’s rich exhibition history.

Each year, thousands in Santa Fe attend new exhibition openings to view art works, study rare objects, or learn about interesting topics from both near and far. People gather not only to see the items on display, but also to see each other, participating in a long-standing social tradition that offers a shared cultural experience in a trusted space. The process of collecting, selecting, and arranging cultural objects for public view in Santa Fe has been repeated here for over 130 years—but how did it all begin?

Exhibitions in the Early Days

It might be tempting to think that the first public exhibitions in Santa Fe started in 1909 with Hewett’s Museum of New Mexico, but in reality, community interest began much earlier. In February 1880, the first railroad engine steamed triumphantly into Santa Fe. The train’s arrival brought new people and possibilities to this once-isolated region. Some passengers were tuberculosis patients drawn to New Mexico in hopes that the dry climate could cure them. Many others were tourists who took keen interest in the wonders of the ancient capital city. Territorial boosters and politicians had already recognized that New Mexico was a unique destination. The dream of a robust tourist economy predated the railroad. A May 1877 edition of the Las Vegas Gazette implored summer vacationers in Colorado to take a stagecoach south. “Tourists and travelers coming to the Rocky Mountains this summer will do well to make a short trip to New Mexico….The naturalist, the geologist, the antiquarian, and the mineralogist can here be interested, enlightened and benefited. Come down and see us.”

Recognizing New Mexico’s tourism potential, a group of Santa Fe businessmen began to openly advocate for an organization that could collect and display the region’s cultural and historical treasures. A December 1880 column in The Santa Fe New Mexican proclaimed: “Indeed the entire country is interested in the history of New Mexico and Santa Fe being the capitol of the Territory and its oldest city, it is eminently proper that there should be a historical society here.” L. Bradford Prince, chief justice of the New Mexico Territorial Supreme Court and future territorial governor, followed up with an editorial that wholeheartedly endorsed the idea, adding a sense of urgency to the matter. He suggested that a historical society could stem the outward flow of “relics” from the territory: “Already it is becoming far more difficult than heretofore to obtain the best specimens of antique stone, implements and pottery, as they are being collected and taken from us by tourists and antiquarians.” Prince lamented that the Smithsonian Institute had already taken huge quantities of the best objects.

Encouraged by the favorable publicity, civic leaders acted before the year was out, establishing the Historical Society of New Mexico and making plans to build a permanent exhibition in Santa Fe.

A Museum in the Palace

By 1885, the Historical Society was ready to go public with Santa Fe’s first permanent exhibition. It had taken time and considerable effort for members to gather a worthy collection and secure the long-term use of the Palace of the Governors, recently vacated by the territorial legislature. The grand opening on September 24, 1885 was the event of the season, with over 200 visitors in attendance. Guests included many dignitaries including Governor E.G. Ross and Justice L. Bradford Prince, who now served as the Society’s president. Civic leaders were particularly proud of this accomplishment, always aware that high-minded institutions such as a museum might help New Mexico’s chances for statehood.

The exhibit rooms presented a wide array of items donated by the public, including an impressive collection of New Mexican minerals. The exhibition featured Native American pottery, old Spanish and Mexican weapons, furniture, wagon wheels, signs, tools, bound collections of Santa Fe newspapers, and even depictions of Our Lady of Guadalupe painted on elk skin. It was reported that the “Mexican and Indian” items on display had been purchased from none other than Jake Gold himself, the reigning curio king of Santa Fe.

Curios on Burro Alley

The coming of the railroad also inspired savvy retailers in Santa Fe to promote their own collections of antiquities and cultural curiosities. Santa Fe proprietor Jake Gold operated a curio shop on San Francisco Street, advertising it as “Gold’s Free Museum.” Retailers used this term loosely to describe merchandise in the form of collections of Native American and Mexican curios. It was less Smithsonian and more P.T. Barnum, but early railroad tourists flocked to browse and purchase from the collections. At Gold’s, visitors would be greeted at the door by a talking parrot and be entertained by Mr. Gold himself as he spun fascinating, if not always truthful, tales about his wares. A reporter writing for the Weekly New Mexican Review in June 1894 described his experience at Gold’s:

“In this shop of Jake’s you can purchase the last pair of trousers worn by Columbus, the sword De Soto wore, the hat of Cabeza de Vaca or the breastplate of silver worn by Cortez; that is, if Jake thinks you want any of these things after hearing you talk, and ‘sizing you up,’ he will call into play an eloquence so convincing and an indifference about selling, acted so genuinely, that you fain would believe….Some tourists go to Santa Fe only to see old churches, others to paint in the Archbishop’s garden, but to us the greatest interest in Santa Fe centers in that little shop on San Francisco Street and Burro Alley.”

While Gold’s intentions were not as high-minded as those of the new Historical Society members, the popularity of his “free museum” further demonstrated the public’s undeniable interest in exhibitions of all kinds.

The appearance of the exhibition mostly followed museum designs of the time: cluttered Victorian arrangements with objects closely packed within dark wood cases and glass enclosures. The walls supported a dense mix of paintings, photographs, animal skins, antlers, and religious carvings, using nearly all available space. In a number of cases, similar artifacts were grouped together, intending to impress by sheer quantity. The result was reminiscent of a modern-day antiques store, chockablock but intriguing nonetheless.

Both the press and public were duly impressed with the exhibition, as the Weekly New Mexican Review reported: “Rare old curiosities are coming in and placed almost daily. During Saturday last there were visitors at the rooms from Indiana, Missouri, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and New York.”

Overall, the Historical Society’s collection was modest compared to those displayed in the well-established museums back East, but it was a beginning. Santa Fe could now claim its own museum exhibition to attract and impress the growing number of tourists. For the next 25 years, this collection in the Palace served as Santa Fe’s only public museum. Things might have stayed that way indefinitely, if not for a new development in 1909 that changed everything.

Museum of New Mexico

“Old Palace Sees New Splendor—New Museum Formally Opened” proclaimed an August 1910 headline of The Santa Fe New Mexican. On the evening of the August 20, visitors from across the country converged in Santa Fe’s Palace of the Governors to attend the grand opening reception of the Museum of New Mexico. The museum was one part of a larger plan that had been hatched in 1907 by archaeologist Edgar Lee Hewett when he and other influencers founded the School for American Archaeology in Santa Fe. Because School faculty and students had amassed substantial quantities of Pueblo pottery and other Indigenous artifacts, Hewett proposed to open a new museum and place these items on public display. The 1909 Territorial Legislature made his plan a reality and established of the Museum of New Mexico, headquartered in the Palace of the Governors. While the School remained a private organization, the Museum of New Mexico was operated and funded by the territorial government. Both institutions were to be directed by Hewett in an unusual public-private arrangement.

The Museum of New Mexico’s placement in the Palace of the Governors caused immediate tension between director Hewett and L. Bradford Prince, still president of the Historical Society of New Mexico. The Society had occupied the east half of the Palace for 25 years, and Prince resented that the new museum, and Hewett in particular, was granted oversight of the entire Palace. For his part, Hewett would have liked to evict the Historical Society altogether, but the New Mexico Legislature insisted that both parties would have to share the building, with the Museum of New Mexico occupying the west rooms. Neither side was pleased with the arrangement, but Hewett had the upper hand and lost no time making plans to renovate the entire building inside and out.

Despite their turf war, both men shared common goals. Each recognized that the territory possessed impressive historical and archaeological artifacts. Each was adamant that these items should remain in New Mexico and be exhibited to the public. Both believed that their museum exhibits provided legitimacy in the push for future statehood. Still, neither could appreciate the other’s approach: Prince preferred the status quo, while Hewett and his supporters had more progressive ideas.

Since 1885, ideas about museums had evolved. New thinking meant new ways of collecting and displaying artifacts. Neither Hewett nor his supporters held the existing Historic Society collection in high regard, believing the old exhibitions to be disorganized and amateurish. Museum of New Mexico Regent and famed newspaperman Charles F. Lummis argued this point in a 1909 Albuquerque Morning Journal article: “No other part of the United States compares with New Mexico in romantic history. But what have you got out of it? Out here in California we have saved by the phonograph hundreds of your songs. In Washington in the national museum they have thousands of specimens of your antiquities. In Santa Fe you had a jumble of unidentified curios. The movement of the American School means that you will have in New Mexico a museum of the last thousand years of this wonderful territory.”

Compared to the densely packed rooms of the Historical Society, the Museum of New Mexico exhibits presented a clear sense of order. Head builder Jesse Nusbaum mindfully adapted the newly remodeled rooms (named “Puye” and “Rito del los Frijoles”) for museum use, with inset shelving built along the walls. Rows of ancient pottery arranged by region neatly lined the displays. Recognizing that visitors should be informed about the objects on display, museum staff built several free-standing wooden kiosks that displayed additional information. The most admired features of the exhibition rooms were the inset wall paintings, by Carl Lotave, a Swedish-born portrait and landscape painter. The paintings depicted panoramic landscapes that provided geographic context for the artifacts displayed in the room. The New Mexican observed: “There seemed to be no disposition on the part of the vast majority to hurry through the rooms but nearly everyone actually studied the paintings and collections and did this in the right way, sitting on settees over which hung gorgeous blankets.”

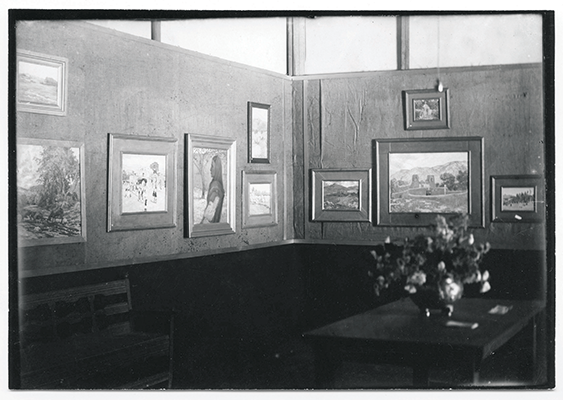

Buoyed by the grand opening’s success, Hewett began to see potential growth for the museum into areas beyond archaeology. He soon became a dedicated supporter of the emerging Santa Fe and Taos art communities, hosting a steady series of painting exhibitions in the large west room of the Palace. Santa Fe was invigorated by the flurry of cultural events hosted by the museum.

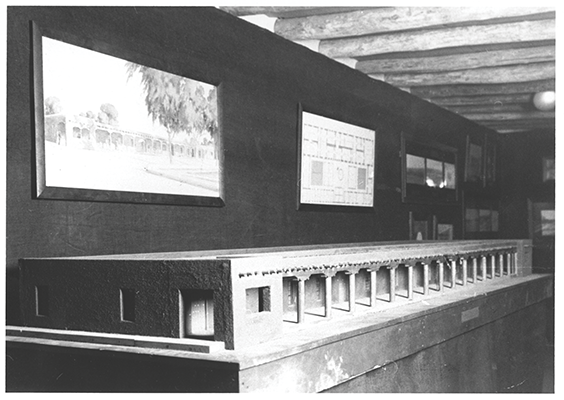

By late 1912, citizens of the capitol city were eager to participate in the latest cultural conversation: the New-Old Santa Fe exhibition. Happily, it turns out that Sylvanus Morley’s concerns were unfounded—Jesse Nusbaum and crew had completed the work on time. The exhibition opened as planned on the evening of November 18. Morley’s displays made it easy for the public to envision a future where Santa Fe Style reigned supreme. Visitors encountered a gallery richly lined with detailed maps, photographs, and drawings. Of particular interest was an impressive scaled model of the Palace of the Governors, its exterior remade in the Pueblo Revival style. Popular and persuasive, the exhibition ultimately helped change the course of Santa Fe’s architectural destiny.

Over a century later, the story of New-Old Santa Fe is on public view within the 2018 On Exhibit installation. Morley’s forward-thinking exhibition is remembered as a milestone event, not only influencing public opinion, but also future curators and designers in the Museum of New Mexico.

On Exhibit: Designs That Defined the Museum of New Mexico is on display in the New Mexico History Museum through July 28, 2019.

(You can read Part 2 here).

David Rohr is the director of the Museum Resources Division and Exhibit Services in the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs and art director of El Palacio. He is the curator of On Exhibit: Designs That Defined the Museum of New Mexico.