They Came to Heal and Stayed to Paint

The artists, their boss, and the gallery

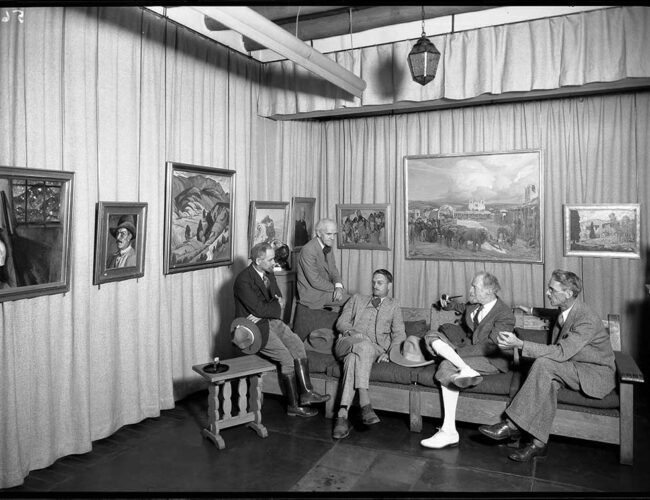

Artists Carlos Vierra, Gerald Cassidy, Theodore Van Soelen, Sheldon Parsons, and Daus Myers, La Fonda Hotel, Santa Fe, New Mexico, ca. 1925. Photograph by T. Harmon Parkhurst. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archive (NHMH/DCA), Neg. No. 020786.

Artists Carlos Vierra, Gerald Cassidy, Theodore Van Soelen, Sheldon Parsons, and Daus Myers, La Fonda Hotel, Santa Fe, New Mexico, ca. 1925. Photograph by T. Harmon Parkhurst. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archive (NHMH/DCA), Neg. No. 020786.

BY NANCY OWEN LEWIS

“The people in this part of the country have about as much use for an artist as their burros have for a fiddler’s midsummer night’s dream,”

complained Carlos Vierra in a letter sent to his sister on August 15, 1904. Vierra, who had studied art at Mark Hopkins Institute in San Francisco, came to New Mexico not to paint, but to heal from a deadly disease. Born in Moss Landing, California, to Portuguese immigrants, Vierra had been working as a marine illustrator in New York City when he developed tuberculosis. Seeking a healthier climate, he moved to Pecos, seventeen miles southeast of Santa Fe, where a family acquaintance owned a ranch. “I expect to stay here two or three months,” he told his mother, hoping a rugged outdoor life would restore his health.

A handful of artists formed Santa Fe’s art colony in the early 1900s. Like Vierra, they originally came to New Mexico not to paint but to heal from tuberculosis, the leading cause of death in America at the time. As a result, it followed a very different trajectory than the art colony at Taos. Artists Ernest Blumenschein and Bert G. Phillips, who “discovered” Taos in 1898 after their wagon threw a wheel outside town, had been trained at the Académie Julian in Paris, along with four of the six original members of the Taos Society of Artists, founded in 1915.

In contrast, Santa Fe’s art colony developed in tandem with the health-seeker movement. Carlos Vierra, Gerald Cassidy, Sheldon Parsons, and Kenneth Chapman attended different art schools. Their careers also differed. Prior to their arrival in New Mexico, the first three worked in New York City, while Chapman worked at an engraving studio in Milwaukee.

The first (mostly) Anglo artists to establish permanent roots in Santa Fe would play a key role in what became the New Mexico Museum of Art. At the time of their arrival, however, Santa Fe was a town of scarcely 5,000 people. It had “no paved streets, no automobiles, and one sewer line,” noted Gerald’s wife, Ina Sizer Cassidy. “A passenger could ride all over town in a horse-drawn taxi for a quarter.”

As the terminus of the Santa Fe Trail, Santa Fe had once been the largest, most important settlement in the territory. In 1878, the railroad changed that. Unlike Albuquerque and Las Vegas, the territorial capital lay in a steep basin unsuitable for the main track. Within the next thirty years, New Mexico’s population doubled, while Santa Fe’s shrank by nearly twenty-five percent.

To attract visitors, local leaders promoted Santa Fe as a tuberculosis health resort. Although Robert Koch discovered the tubercle bacillus in 1882, effective drugs would not come into play until the 1940s. During the intervening years, the only medically approved recourse was nutritious food, fresh air, and rest, preferably in a high, dry, and sunny climate. Even within its railroad-unfriendly basin, Santa Fe’s elevation still clocked in at a formidable 7,000 feet. City boosters touted its therapeutic properties in local pamphlets, describing Santa Fe as the “queen of health resorts.”

Despite this puffery, Santa Fe offered few amenities. But upon recovery, all four artists chose to remain. They likely feared relapse. As Chapman explained, “I have regained my health in New Mexico, and experience had taught me not to risk leaving the Southwest.” But there was another compelling reason: Edgar Lee Hewett, founding director of the School of American Archaeology and Museum of New Mexico, provided studio space, hosted exhibits of their work, and gave them jobs.

Tuberculosis had also brought Hewett to New Mexico. He was teaching in Colorado when his wife, Cora, became ill. Hoping that fresh air would heal her lungs, he put her in a camp wagon and toured New Mexico. In 1898, he became president of New Mexico Normal University, now Highlands University. Sadly, shortly after his five-year contract ended, Cora died of TB. But by that time, Hewett had developed a passion for Southwest archaeology. In 1907, the Archaeological Institute of America appointed him director of the School of American Archaeology. The Institute hoped its newest school would professionalize a discipline whose practitioners seemed more concerned with museum collections than scientific research.

The first thing that Hewett did, however, was establish a museum. In 1909, the Territorial Legislature granted Hewett approval to establish the Museum of New Mexico and to house both institutions in the Palace of the Governors. Hewett trained students and excavated sites, but instead of scientific studies, he aimed his publications at a popular audience. Colleagues complained that he was more of a promoter than a scientist. Involving art, however, enabled him to do both. Under his direction, the Palace of the Governors hosted exhibits and provided studio space. As he explained, “We find that from the peoples of the past it is mainly their fine arts that have survived. Art is the great, lasting, self-revealing activity of life. Through it we transmit our spiritual power through the ages.”

Trained at the Art Institute in Chicago, Kenneth Chapman began experiencing pulmonary problems while employed at an engraving studio in Milwaukee. An acquaintance recommended New Mexico to Chapman after returning from the area “fit as a fiddle.” The 1899 move proved beneficial, for Chapman recovered his health and also met Hewett, then president of New Mexico Normal University, who offered him a job teaching art. A decade later, Hewett, now director of the School and Museum in Santa Fe, hired Chapman as secretary, illustrator, and manager of the artifact collections. This led Chapman to become intrigued by the symbols on pottery fragments, and he soon embarked on a study of design motifs.

In 1912, after eight arduous years in Santa Fe, Carlos Vierra joined Hewett’s staff. As he explained to his mother, “When I stop to think of the useless years I have had to live in such a country as this with so many things against me, I sometimes wonder why I am still alive.” In 1905, he had purchased a photography studio, but sold it a few years later, as the indoor work nearly killed him. Although still interested in photography, he had developed a new passion. At a time when popular American styles had begun to replace traditional adobe architecture, Vierra joined other staff members to reverse this trend.

Appointed director of exhibits for the 1915 Panama–California Exposition in San Diego, Hewett employed Santa Fe artists to help with the event. Vierra installed murals depicting six Maya cities, five of which he painted at his studio at the Palace of the Governors, where they were shown to the public before being shipped to San Diego. Chapman designed the Painted Desert exhibit, while Gerald Cassidy painted The Cliff Dwellers of the Southwest. The event also provided an opportunity for these relatively unknown artists to show their work in a national venue. Cassidy exhibited Cui Bono?, depicting a man from Taos Pueblo, while Chapman’s drawings of bird motifs introduced exposition attendees to Southwest Indian pottery designs.

Three months after the exposition opened, the New Mexico Legislature appropriated funds for an art museum in Santa Fe. Businessman Frank Springer provided the required matching funds, and commissioned Chapman and Vierra to complete a set of murals for the building’s auditorium. Chapman later designed furniture for the new museum as well. The mural commission had originally been awarded to Donald Beauregard, who was too ill to finish the job. Knowing that death was imminent, he recommended that Sheldon Parsons complete his work. Parsons had studied at the National Academy of Design in Rochester, and had been a successful portrait painter.

Parsons contracted tuberculosis while working in New York City. After a period of remission, the disease flared up following the death of his wife in 1913. Parsons and his daughter Sara were en route to San Francisco, where he had a mural commission, when he suffered a relapse. By the time the train reached Denver, he was seriously ill. Parsons took his doctor’s advice and headed to Santa Fe, hoping the climate would heal his lungs. At the time of Beauregard’s recommendation, he was still convalescing. Because Hewett didn’t want to risk losing another artist, Chapman and Vierra completed the murals.

As plans for the new museum moved forward, the Palace of the Governors hosted its first annual exhibition of Santa Fe artists. The show, which opened in August 1915, featured the work of Chapman, Vierra, Parsons, and Cassidy, who arrived that year.

Born in Covington, Kentucky, Cassidy grew up in Cincinnati, where he studied at the Institute of Mechanical Arts. After receiving additional training in New York, he became a successful draftsmen and lithographer. Then at age thirty, Cassidy was diagnosed with tuberculosis and sent to Albuquerque to heal. Upon recovery, he moved to Denver, where he worked as a lithographer. While there, he married writer Ina Sizer, who encouraged him pursue a career as a painter. Searching for a suitable place to live, they visited Santa Fe in 1912 and decided to make it their base, as “it was near a telegraph, a railroad, and in a community with subjects for him to sketch.” Three years later, they bought a house on Canyon Road. While Cassidy painted, his wife immersed herself in the community, becoming a member of the League of Women’s Voters and later serving as state director of the Federal Writer’s Project.

The fact that this small community of artists flourished was due in no small measure to the women who accompanied them. Despite the hardships, they embraced life in Santa Fe. Sara Parsons was only twelve when she and her desperately ill father arrived. The community welcomed them, and found them a two-room apartment near the plaza. In gratitude, the Parsons invited their new friends to a five-course Thanksgiving feast, which Sara cooked on a two-burner oil stove. As her father recovered, Sara began to paint. She exhibited her work at the Second Annual Santa Fe Art Show. When she was eighteen, she married artist Victor Higgins and moved to Taos.

In 1910, Carlos Vierra married Ada Ogle, a high school teacher he met in Santa Fe. The wedding took place in Hutchinson, Kansas, her hometown. He brought her back to Santa Fe, with “no place we can call a home.” But embracing the life he had to offer, she accompanied him on research trips and joined him in San Diego for the Panama–California Exposition. She participated in Springer’s 1915 expedition to El Rito de los Frijoles, and on April 4, 1922 was elected secretary of the Arts Club. She also advised her husband on construction details, convincing him, as he began work on their new home, that it really did need a kitchen.

Chapman met his future wife in Santa Fe shortly after her arrival in 1910. Originally from Philadelphia, Katherine Muller had signed up for Hewett’s summer archaeology program. She soon met Kenneth Chapman, who was one of the lecturers. “Even if I had wished, I could not well have avoided meeting her,” he explained. “For weeks, wherever I turned, she was usually in the thick of it.” Kate, who had attended the Philadelphia Art School, became immersed in efforts to preserve traditional architecture. By 1914, she had a studio at the museum, where she taught and gave lectures. She and Chapman joined the Vierras on Springer’s 1915 expedition to El Rito de los Frijoles, where they made over 100 sketches of rock art. On September 30, 1915, the couple was married at the St. Francis Cathedral. Two years later, they purchased an adobe house on Acequia Madre. After their two children were born, Kate embarked on a career renovating and designing adobe houses.

Other artists settled in Santa Fe. In 1916, William Penhallow Henderson came with his ailing wife, poet Alice Corbin Henderson, who was admitted to Santa Fe’s Sunmount Sanatorium. The following year, artist Arthur Musgrave arrived. He had developed TB while serving in the British army. Upon discharge, his doctor sent him to the Southwest to recover his health. Having heard about Santa Fe’s art colony, Musgrave wrote to the museum, inquiring about lodging. In response, Paul A.F. Walter sent him a list of suggestions and an El Palacio article on “The Santa Fe–Taos Art Colony.” Both Musgrave and Henderson would exhibit their work at the art museum’s inaugural show.

Art had now become an essential part of the School of American Archaeology’s mission. At Hewett’s urging, on February 3, 1917, the school changed its name to the School of American Research “to better reflect a mission that also embraced ethnology, linguistics, and art—in fact the entire group of subjects that proceed from the study of man.”

The new art museum opened November 25, 1917. People flocked to the St. Francis Auditorium to hear the speeches, but it was the art displayed in the museum’s galleries that would keep them coming back. The inaugural art exhibition featured 172 paintings by forty Southwestern artists, including works by Vierra, Chapman, Parsons, and Cassidy, who donated Cui Bono? to the collection.

Following the dedication, Hewett appointed Parsons curator of the art museum, while Chapman and Vierra continued to work for the School of American Research. As the decade drew to a close, Santa Fe’s first resident artists not only recovered their health; they also laid the foundation for a growing art community. But in the process, their own art had changed. Gerald Cassidy, formerly a lithographer and draftsman, became known for his luminous Southwestern vistas and native portraiture. Sheldon Parsons, who had once painted portraits of notables such as Susan B. Anthony, now produced impressionistic New Mexico landscape paintings. Carlos Vierra, formerly a marine illustrator, became a major proponent of the Spanish-Pueblo Revival style, and in 1918 began construction of his own adobe home. Commercial artist Kenneth Chapman became an authority on Indian art.

The 1920s had its own influx of artists, among whom many sought healing as well. Will Shuster, a twenty-six-year-old efficiency engineer from Philadelphia, was one of them. He arrived March 3, 1920, after contracting TB following military service in France. He recovered, and became a prominent Santa Fe artist (and originator of Zozobra). In 1934, the art museum commissioned him to paint a series of murals honoring the spiritual, ceremonial, and agricultural traditions of the Pueblo Indians—a theme suggested by Hewett and funded by the Federal Emergency Relief Administration. Many of the over 7,600 centennial celebrants who filed through the museum on November 25, 2017 saw these murals in the courtyard of the New Mexico Museum of Art—not only an intriguing counterpoint to the murals adorning the walls of the St. Francis Auditorium, but a reminder of the inadvertent role tuberculosis played in making Santa Fe into the world-renowned art destination it is today.

Nancy Owen Lewis is a scholar-in-residence at the School for Advanced Research and the author of Chasing the Cure in New Mexico: Tuberculosis and the Quest for Health and A Peculiar Alchemy: A Centennial History of SAR, co-authored with Kay Leigh Hagan.