Drawing Near To The Divine

A British Museum Touring Exhibition Brings Rubens, Da Vinci, and Michelangelo Drawings To The New Mexico Museum of Art

BY ISABEL SELIGMAN

“SUPPOSE ONE COULD CATCH THEM BEFORE they become ‘works of art?’ Catch them hot & sudden as they rise in the mind.” In her diary, Virginia Woolf examined the stuff of thought, its shape and contours as well as its inherent slipperiness. While she was largely concerned with literature, her questions apply just as well to the visual arts. What does an idea look like before it is labored over, crafted, and shaped into a finished piece?

The answer, for artists, is usually a drawing. Drawing provides a means of expression unhindered by materials or labor—the opportunity to act and communicate almost at the speed of thought. Drawings thus offer privileged insights into an artist’s mind at the moment of creation. What better place for a student of art to begin? While now out of fashion and often considered regressive, inauthentic, or derivative, copy drawing was once the foundation of any artistic education. A cornerstone of the Renaissance workshop, the artist Cennino Cennini, author of one of the first manuals on painting, considered it so vital that in The Craftsman’s Handbook (written around 1399) he advised students to begin by drawing from an existing model every day, for “No matter how little it is, it will be well worth while, and will do you the world of good.” After the foundation of the Louvre in the eighteenth century, the National Assembly decreed that five days out of every ten were reserved solely for artists to copy, one of the primary reasons the museum came to be known as “the laboratory of French art.”

This article grew out of a three-year project supported by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation to encourage art students to visit the collection of prints and drawings in the British Museum, to be inspired by them, and to draw from them. The first strand of the project was a program of workshops in the British Museum for students at art schools in and around London. The second was a touring exhibition of drawings from the collection, which had been road tested during these workshops, an opportunity to discover those drawings students found the most engaging and exciting. The exhibition’s curators conceived it particularly to appeal to artists and art students beyond London, and since it includes some of the undisputed highlights of the museum’s collection, it can be enjoyed by anyone wishing for insights into the processes of both drawing and thinking. Having recently completed its UK tour of three venues associated with art schools, Lines of Thought: Drawing from Michelangelo to Now opened at the New Mexico Museum of Art on May 27th, and will travel to the Rhode Island School of Design Museum in September of this year.

Like the Louvre in the eighteenth century, the British Museum also has a longstanding tradition of individual artists using its collection for inspiration. Today, it holds one of the world’s richest collections of Western prints and drawings, over two million works on paper from the Renaissance to the contemporary, which the public can consult in the department’s Study Room. Until two years ago, however, there were no formal partnerships with art schools. In 2014, only two art student classes were scheduled for a visit. When the museum initially approached professors at art schools to discuss the possibility of workshops, the reaction was that students might be hostile to drawing and were more likely to keep a blog than a sketchbook. This refrain was familiar to the artist Bridget Riley, in its spirit if not its letter, from her time as an art student in London in the 1950s. By the time she was a student at Goldsmiths, University of London, the institution already viewed drawing as something that could be dispensed with. Life drawing classes were optional, and it was only due to Riley’s own conviction that it could benefit her artistic development that she enrolled in them. She also went to the British Museum Study Room to see drawings by past masters for herself. Riley has credited observational drawing as the key to all of her subsequent discoveries in painted abstraction, noting in her essay “At the End of My Pencil” (2009), “It is this effort to ‘clarify’ that makes drawing particularly useful, and it is this way that I assimilate experience and find new ground.”

SINCE Riley’s student days copying drawings, including assiduous inquiry into the methods of masters such as Georges Seurat and Henri Matisse, her continual interrogation of the mechanics of optical phenomena, and key role as a leading figure in the Op art movement, ensured her recognition as one of the world’s foremost contemporary artists. She established the Bridget Riley Art Foundation in 2011. Hoping to ensure that other students might have such access to drawings of the highest quality, the foundation initiated an ambitious, three-year project to allow art students to discover the incredible resources offered by the British Museum’s graphic collection, and inspire them to draw themselves. Over the past two years, a small team, comprising Sarah Jaffray, Rebecca Birrell, and me, have led more than a hundred workshops at the Museum for over 1,000 students practicing in all areas of fine art, including painting, sculpture, performance, installation, video, sound, photography, and film. Our aim was to re-introduce drawing as a fundamental and transformative tool in each of these disciplines.

We wanted to illustrate the broadest chronological range, from the fifteenth century to the contemporary, in the widest possible range of media. Ink as used by Francisco Goya and Rachel Whiteread, red chalk by Jean-Antoine Watteau and Edda Renouf, drawings in charcoal by Albrecht Dürer and Willem de Kooning, and silverpoints by Paul Noble and Raphael. From inchoate doodles to highly finished presentation drawings, we wanted to give students a taste of the treasures available. In addition to an introduction for students, we saw these workshops as fact-finding missions. They allowed us to identify students’ interests, modes of practice, and engagement. How, if at all, did drawing feature in their practice, and how could looking at other types of drawings develop this?

The impetus behind the touring exhibition had been to give art students outside London access to drawings of the highest quality. The workshops were a real opportunity to work in dialogue with a similar audience and to ask them questions about how they perceived drawing, its function, and its possibilities. In addition to our discussions, we handed out feedback questionnaires so that we could get some of these answers on paper. They have proved to be a valuable resource.

Many students questioned the idea of drawing from drawings, and were initially resistant to it. We found it necessary to explain that from its very inception drawing from drawings was neither mechanical nor innocent. The process is not an effort to replicate a work, but to understand it, and it’s thus an intellectual as much as a manual exercise. Cennini recommended that students draw “only a little each day, so that you might not come to lose your taste for it,” while Joshua Reynolds advised students at the Royal Academy in London, “Instead of copying the touches of those great masters, copy only their conceptions.” The process is not necessarily the attempt to acquire a skill, so much as questioning what a skill might look like, and this endeavor to learn from the achievements and mistakes of others can also become an investigation of one’s own practice. When alienated from his artistic contemporaries, Henri Matisse went to the Louvre to make copies, in his words, “to understand myself.”

Some wonderful examples of such analytical and interpretive drawings were recently on display at the British Museum, where last year student works were shown beside the drawings that had inspired them. Two different approaches led one student, Ying Zhou, to create her own drawn response. The first was a mode of looking implied in a drawing by the contemporary artist Ariane Laroux, seen as if through an accumulation of discrete glances. The second was a study of sculpture by Paul Cézanne drawn continually over the course of thirty years. Drawn from photographic collages of fractured statuary, Zhou’s work seems to crystallize numerous glimpses into a kaleidoscopic melee, while also making striking use of the empty reserves of the paper in a manner that responds to the work of both Cézanne and Laroux. Another student, Eliza Wimperis, was moved by what she called the “peculiar physicality” of a gestural spiral form in a charcoal drawing by the German artist Elke Wagner. In order to examine this, Eliza drew her response not by hand, but with the pencil attached to her foot as it moved through the five classical ballet positions . As well as exploring the technical restraint and control of the body as a means of expression across disciplines, her response also exemplifies the translation of bodily movement to marks on a page that lies at the heart of all drawing.

After we used these workshops as a testing ground to find out which sorts of drawings students found particularly engaging, our next challenge was to come up with an exhibition structure that might embrace all of them. The twentieth-century conceptual and performance artist Joseph Beuys referred to drawing as his “thinking medium,” and this is a particularly apt phrase because it reveals the duality of the process, which is both a vehicle for recording thought and prompting it, a medium in which to think. There are numerous art historical precedents for this conception of drawing: the sixteenth-century art historian Giorgio Vasari referred to drawings as thoughts, and the seventeenth-century critic Roger de Piles described drawing as “the manner in which the Painter thinks things.” Lines of Thought: Drawing from Michelangelo to Now is thus structured around the premise of drawing as a thinking medium, with works grouped not chronologically, but according to the different types of thought process that drawing both records and demands. Initial thoughts, brainstorming, inquiry, association, and development are all visible in drawings by artists working centuries apart, and bringing their work together demonstrates what can be learned from looking at masters of the past in the context of those working today.

THE exhibition opens with a brief introduction to the vast chronological sweep of drawing as a thinking medium, showing second thoughts and revisions in drawings made nearly 3,000 years apart. The first is a sheet of papyrus showing a spell from the Book of the Dead, made in 940 BC. It shows the final judgement scene where the priestess Nestanebtasheru’s heart is being weighed. At first glance, the drawing might seem static and finished, but closer inspection reveals red draft lines where the anonymous artist originally planned out the composition. In this way you can also see the artist’s numerous modifications and adjustments, sensing the movements of a hand and mind 3,000 years ago. The second is a contemporary drawing by the British artist Michael Landy, Study for Break Down, 2000, a plan for a piece in which the artist destroyed all 7,227 of his possessions. Both drawings are concerned with ritual and performance, and both are also maps for a potential afterlife. As Landy’s drawing only escaped destruction because he gave it away to his dealer (who subsequently donated it to the museum) before the start of the piece, both drawings are also startling relics of a process which should have resulted in their annihilation.

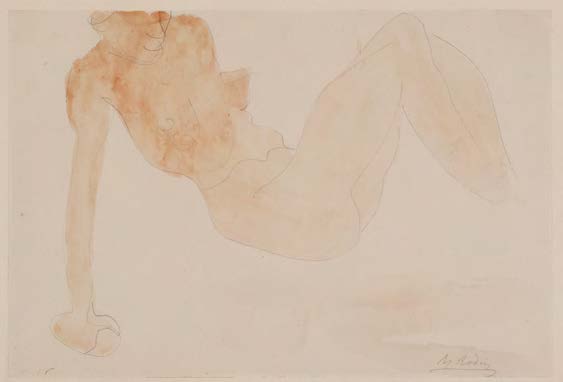

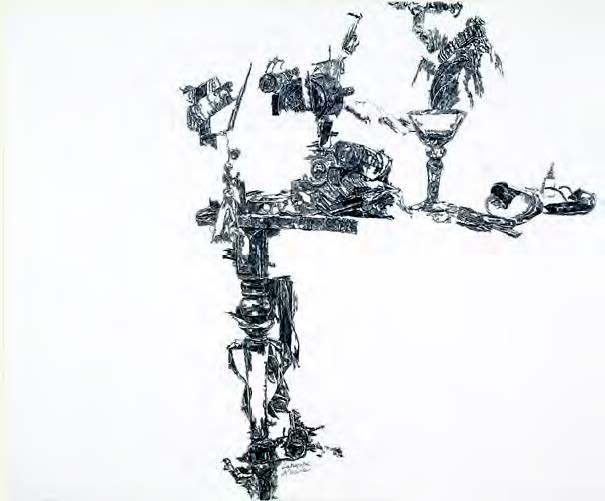

The exhibition’s subsequent sections take us through five different types of thought processes fundamental to artistic creation, beginning with the recording of initial thoughts, ideas, and impressions. Drawing is often the fastest and easiest way to externalize an idea, acting almost at the speed of thought. Historically described as primi pensieri or “first thoughts,” this type of exploratory drawing can provide clues as to how artists approach problems or proposals, formulate questions for themselves, or how the germ of an idea is born. Two such germs are visible in works by Auguste Rodin and Peter Paul Rubens (figs. 5 and 6). According to his contemporaries, Rodin used to dash off drawings without taking his eyes off the model, “with only his brain to guide it.” While Rodin reputedly produced scores of these drawings per day, a mere handful would be selected for further development. Similarly, Rubens’ frenzied depiction of dancers is so speedily penned, they almost seem to be escaping from the page. In their abbreviated form, the figures contain an energy suggesting the very earliest stages of an idea.

As well as catching initial ideas, drawing can also be used to generate multiple ones through brainstorming. This method hinges upon excess, where an artist throws down a profusion of ideas onto the page, many of which will be discarded. In generating multiple possibilities, brainstorming provides a vital space for the testing of ideas, placing them side by side for comparison, or on top of one another in a palimpsest. It enables a kind of thinking through doing, and evaluation is avoided until a later stage. A fabulous example is Michelangelo’s study for the Last Judgement on the wall of the Sistine Chapel. Grappling with configurations of falling and twisting bodies, we have an incredible insight into an extremely flexible stage of the working process. Three crouching figures at upper left are most likely an alternative idea for those directly below them, yet while most figures made it into the final composition with minor adjustments, only one, the angel strangling the damned soul, at center left, was removed, perhaps deemed too unorthodox for the papal chapel. Likewise, in a drawing by Richard Hamilton in which he imagines a scene from the “lotus eaters” episode in James Joyce’s Ulysses, the text describes Leopold Bloom’s genitals as “a languid floating flower.” While there are numerous attempts at many types of flowers, there is also a mushroom, perhaps left for the sake of further ideas it might spark.

THE third section explores drawing as a method of inquiry, showing observational studies, and methodical and system-based drawings, alongside inquiries into the nature and process of drawing itself. Here, the exhibition examines life drawing and the formal probing of abstract elements, along with works that inquire about the properties of materials and push the boundaries of drawing as a practice. Works by Paul Cézanne and Stephen Willats both show the intense investigation of still life elements. Cézanne’s obsession lasted over thirty years, as he continually drew the sculpture from different angles and in combination with other objects. Meanwhile, Willats’s Conceptual Still-Life creates links between objects on a table verbally, rather than visually, illustrating connections between objects including a tin can, chalk, and the table itself, such as “detachable parts,” “soft in feeling,” and “extensions of the hand.” Figure studies, including one made by Pablo Picasso in 1906–7 during the eighteen months that he was working on his Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, are testament to the enduring power of drawing to examine the human form. Another sparkling study by Georges Seurat examines how the volumes of two fashionably dressed figures will fit into the theatrical setting of his infamous Grande Jatte.

Drawing is an excellent problem-solving tool, but a disciplined analytical method is only one approach to any problem. The process of drawing is particularly conducive to associative thinking, complementing a more rational inquiry with the space in which to explore and dream. Answers often appear in the places we least expect them, and studies suggest that brain mechanisms used to work out a problem methodically are very different from, and yet equally important to, those employed when an answer appears seemingly out of nowhere. A wonderful example is Jean-Antoine Watteau’s perspicacious study of hart’s tongue ferns, from a perspective that asks us to get right down on the ground with him. This also resulted in an unexpected and unconventional view of an eighteenth-century house in the distance, most likely a by-product of the artist’s original inquiry. The impact of chance and its use as a stimulus for associative thought is visible in landscape drawings by Alexander Cozens, who used a “blot” technique to stimulate his invention, and by Ithell Colquhoun, a British surrealist who, in 1954, used automatic drawing in ink as a vehicle for the exploration of the unconscious.

AFTER any initial exploration and experiment, ideas need to undergo a process of development and definition, discarding elements that don’t work, and refining those that do. This process includes as much destruction as creation. In this section, drawings allow us to see artists changing their minds, revising and retracting. Such drawings thus offer us a unique chance to view the minds of some of the world’s most astonishing artists in operation. One such example is Bridget Riley’s study for Blaze, meticulously constructed with the aid of a compass, the dynamic thrust and counter-thrust of the chevrons are obscured in the center by a collaged piece of paper, correcting the central passage. Albrecht Dürer’s study for Nemesis also employed the stylus and compass in its construction—according to a strict canon of Vitruvian proportion, visible in the incised grid underneath the figure—trying out both different wings for the figure of fortune, and correcting the buttocks by replacing them a square higher. Meanwhile, both Claude Lorrain and Leonardo da Vinci exploit the double-sided sheet to develop a drawing by holding it up to the light. While Claude reverses and simplifies his dazzling study of the Roman campagna, Leonardo clarifies his choice for a modification of a Virgin and Child with a cat—the application of wash strengthening one choice and obliterating the other with a stroke of the brush.

So far thousands of students and artists have visited the drawings on their tour of the UK, and in the US they will no doubt continue to spark exciting responses in each of their new contexts. Paul Valery wrote that there is “no art which calls for the use of more intelligence than drawing… every mental faculty finds its function in the task.” It’s my hope that Lines of Thought will enable a new generation of artists to experience the almost endless possibilities drawing allows them; to experiment, to analyze, and above all to think.

Isabel Seligman is the Bridget Riley Art Foundation Exhibition Curator in the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, and curator of the exhibition Lines of Thought: Drawing from Michelangelo to Now.